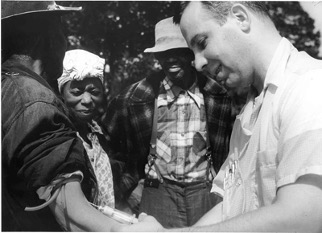

Figure 1: A doctor drawing blood from a patient as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in 1932, National Archives (National Archives, 1932)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

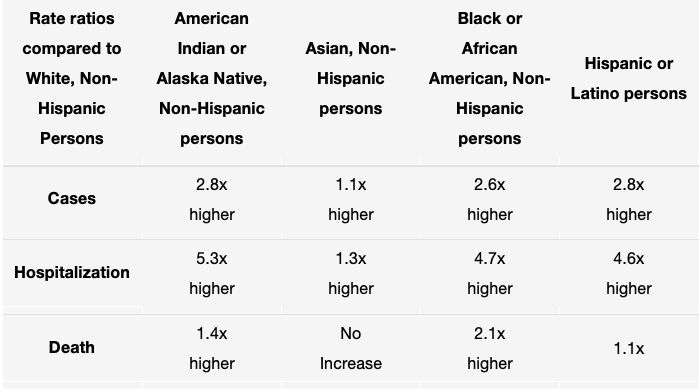

Despite disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death in racial and ethnic minority groups, these vulnerable populations remain heavily underrepresented in COVID-19 clinical trials. Currently, Black, Latinx, and Native American populations exhibit strikingly poor health outcomes relative to the rest of the population, with these minorities being nearly 5 times more likely to be hospitalized and 1.5 times more likely to die from COVID-19 related illness (“COVID-19 Hospitalization,” 2020).

Table 1: COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity (as of August 18, 2020), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“COVID-19 Hospitalization,” 2020).

Despite these outcomes, there are substantial gaps in the clinical understanding about how COVID-19 treatments affect the health of minority groups. A team of researchers led by Daniel Chastain of the University of Georgia’s College of Pharmacy sought to quantify this disparity in COVID-19 clinical trials for minorities. Chastain examined two federal trials of Remdesivir, the most promising therapeutic agent against COVID-19: the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAD) funded Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT-1) and the Gilead-funded study into Remdesivir (GS-U.S.-540-5773) (Chastain et al., 2020).

Data supporting the drug’s efficacy and safety in minority groups was limited, with race and ethnicity not listed for the 53 patients treated under the “compassionate use” program, which provides drugs unapproved by the FDA to treat terminally ill patients when no other treatments are available (Grein et al., 2020). However, for patients not treated under the “compassionate use” program, the results were unsurprising. While both trials included sites throughout the US where Black, Latinx, and Native Americans are overrepresented among COVID-19 patients, the team ultimately found that these minority groups were substantially underrepresented in the study samples.

Chastain’s group determined that in the ACTT-1 trial, Black Americans accounted for only about 20% of the 1063 patients in the placebo-controlled trial. In the Gilead-funded study, researchers found that only 11% of the 397 patients randomly assigned to 5 or 10 days of Remdesivir were Black. The underrepresentation of Latinx and Native Americans was more disheartening. The Gilead-funded study into Remdesivir failed to provide data on Latinx and Native American representation. But even within the ACTT-1, only 23% and 0.7% of subjects were Latinx or Native American, respectively (Chastain et al., 2020). Thus, the team concluded that the modest benefit seen with Remdesivir in these studies may not be generalizable to minority populations.

Recruiting underrepresented minority participants for clinical trials has proven to be challenging. Research conducted by Darcell P. Scharff of Saint Louis University’s School of Public Health found mistrust of the health care system emerged as a primary barrier to participation in medical research among Black participants (Scharff et al., 2010). Minorities have been used as tools of medical experimentation for centuries, most notably evidenced by the United States Public Health Services (USPHS) Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972), which passively monitored hundreds of adult black males for forty years with syphilis to understand the long-term progression of the disease. (Alsan & Wanamaker, 2018). In 1932, the USPHS recruited over 200+ Black men and women under the guise of free medical care for “bad blood,” a colloquial term encompassing anemia, syphilis, and fatigue (McVean, 2019). However, these subjects were not informed that they were not actually going to be treated for syphilis. In the next decade, researchers actively worked to ensure that their subjects did not receive treatment for syphilis, by blacklisting subjects from hospitals in the Alabama Health Department. Nearly two decades later, researchers argued that it was too late to give the subjects penicillin, as their syphilis had progressed too far for the drug to help. By failing to tell subjects about their lack of treatment and actively prevent them from seeking life-saving treatment, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, when revealed, would increase minority mistrust of clinical research for decades (McVean, 2019).

As recently as the 1990s, unethical medical research involving African Americans has been conducted by highly esteemed academic institutions. During the national measles outbreak in 1989, the CDC tested two vaccines on nearly 1,500 minority infants in Los Angeles. However, the CDC failed to disclose to parents that one of the vaccines was experimental and had been associated with increased infant mortality rates in clinical trials held in Africa and Haiti (Gamble, 1997). Ultimately, despite progress made through clinical research in the past few decades, African-Americans fail to fully reap the benefits of these advancements. With minorities less likely to receive routine medical care and face higher rates of morbidity and mortality than nonminorities, people of color continue to face disparities with access to health care, the quality of care received, and health outcomes (Orsi, 2010). Thus, medical distrust stemming from historical trauma, reinforced by systemic racism in the healthcare system, remains the primary obstacle for minority recruitment in clinical trials.

Along with the findings about the trials themselves, Chastain’s team identified a lack of diversity among principal investigators as a possible cause of minority noninvolvement. A diverse group of investigators might help curb bias in the recruitment of underrepresented populations (Chastain et al., 2020). Another way to curb bias is by federal legislation, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) policy mandating the inclusion of minorities in NIH-funded research. In NIH defined phase 3 clinical trials, researchers are required to report outcomes classified by sex, gender, and race/ethnicity (unless existing data suggests that differences are unlikely to be observed) (Oh et al., 2015). Yet, as demonstrated with the phase-3 ACTT-1 Remdesivir study, investigators sometimes fail to provide outcome data according to sex or gender, race, and ethnicity.

Chastain’s team ends by acknowledging the steps that must be taken by federal COVID-19 clinical trials to ensure minority representation. First, researchers must provide appropriate random sampling and expand clinical trial sites, especially within vulnerable communities that have a disproportionate number of high-risk patients. This will help improve the representativeness of samples. Second, standardizing race and ethnicity reporting would allow improved assessment of the generalizability of evidence-based interventions. Writing that both research funders and clinical journals have a responsibility to ensure minority representation, Chastain’s team concludes that representation in clinical trials accountable remains critical in protecting vulnerable populations (Chastain et al., 2020).

To provide the necessary data to generalize efficacy and safety outcomes across racial and ethnic groups, COVID-19 clinical trials must reflect the demographics of the pandemic, especially in the United States. As the pandemic progresses, representation of Black, Latinx, and Native American populations for COVID-19 clinical trials needs to be increased.

References

Alsan, M., & Wanamaker, M. (2018). TUSKEGEE AND THE HEALTH OF BLACK MEN. The quarterly journal of economics, 133(1), 407–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx029

Chastain, D. B., Osae, S. P., Henao-Martínez, A. F., Franco-Paredes, C., Chastain, J. S., & Young, H. N. (2020). Racial Disproportionality in Covid Clinical Trials. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(9). doi:10.1056/nejmp2021971

COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity. (2020, August 18). Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Gamble V. N. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American journal of public health, 87(11), 1773–1778. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773

Grein, J., Ohmagari, N., Shin, D., Diaz, G., Asperges, E., Castagna, A., . . . Flanigan, T. (2020). Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(24), 2327-2336. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2007016

National Archives Atlanta, GA (U.S. government), 1932, Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tuskegee-syphilis-study_doctor-injecting-subject.jpg

McVean, A. (2019, January 25). 40 Years of Human Experimentation in America: The Tuskegee Study. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history/40-years-human-experimentation-america-tuskegee-study

Oh, S. S., Galanter, J., Thakur, N., Pino-Yanes, M., Barcelo, N. E., White, M. J., de Bruin, D. M., Greenblatt, R. M., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Wu, A. H., Borrell, L. N., Gunter, C., Powe, N. R., & Burchard, E. G. (2015). Diversity in Clinical and Biomedical Research: A Promise Yet to Be Fulfilled. PLoS medicine, 12(12), e1001918. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001918

Orsi, J. M., Margellos-Anast, H., & Whitman, S. (2010). Black-White health disparities in the United States and Chicago: a 15-year progress analysis. American journal of public health, 100(2), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.165407

Scharff, D. P., Mathews, K. J., Jackson, P., Hoffsuemmer, J., Martin, E., & Edwards, D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 21(3), 879–897. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0323

Related Posts

When the Going gets Tough, the Close start Nearing: Networks and External Stress

Figure: A Social Network (Wikimedia Commons, Author Zigomitros Athanasios –...

Read MoreDancing Neurons & Their Exciting Impacts

Figure 1: A network of neurons in the brain Source: Elizabeth...

Read MoreAn International Team of Researchers Just Solved One of the Biggest Mysteries About the Human Heart

Figure 1: The heart is one of the most complex...

Read MoreVivek Babu