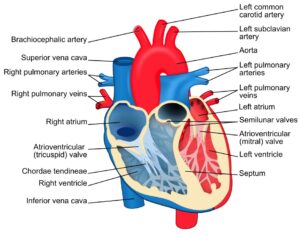

Figure 1: This figure describes some of the symptoms of stress, which can have negative consequences for many body systems

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Hospital workers perform valuable work in caring for the sick and injured, but as part of their work, these workers are exposed to a variety of stressors. In a review of an assortment of studies looking at workplace stress in nursing, A. McVicar (2003) identified several workplace stressors that nurses must face, including workload and time pressure, relationships with other staff, poor leadership, and coping with patient needs and death. In another study looking at 475 practicing attending physicians, Olsen et al. (2019) found that some workplace factors predicting burnout included a lack of control over workload, poor teamwork, having values that do not align with those of leadership, and a hectic work environment. Exposure to stress in the workplace means that these workers may face an array of detrimental health effects. According to a 2017 review by Yaribeygi et al., acute and chronic stress is associated with destructive effects on several body systems, including the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, the gastrointestinal system, and the endocrine system. Consequences arising from stress include impairments in cognition and learning as well as immune function; these impairments may contribute to the development of disease (Yaribeygi et al., 2017). To mitigate the consequences associated with hospital workers’ stress, researchers have developed interventions designed to reduce stress levels and to equip members of this population with tools and strategies to better cope with stress.

One such intervention is the “Caring for the Caregivers” (CCG) approach, an eight-month intervention developed by a team of researchers led by Sarah Sallon, a researcher at the Louis L. Borick Natural Medicine Research Center of Hadassah Hospital. The program consisted of five components: (a) cognitive, including mindfulness techniques such as sitting meditation, (b) somatic, including techniques to increase body awareness through mindfulness such as balancing and postural adjustment exercises, (c) dynamic-interactive, including exercises to encourage movement and expressing emotions through music, sound, and voice, (d) emotive-expressive, including individual and group drawing and writing exercises as well as reflection sessions, and (e) hands-on, including techniques involving activating trigger points using acupressure and palm massage. In their study, Sallon et al. (2017) tested the effectiveness of the CCG approach by recruiting hospital staff at Hadassah Medical Organization. As part of the program, participants took part in a series of 30 weekly sessions followed by a full-day workshop and completed two questionnaires, one before and one following the intervention (Sallon et al., 2017). The researchers found that participants who took part in the intervention reported decreases in job-related tension, perceived stress, and emotional exhaustion from burnout. Furthermore, they also found that participants reported improvements in work productivity, mood, and physical and mental health symptoms.

The results from the study by Sallon et al. (2017) provide evidence for the CCG program as a promising intervention for reducing stress in hospital workers. Furthermore, interventions such as the CCG program may be especially beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic, as healthcare workers during the pandemic may face even more stressors related to the virus. For instance, in a study of over 1000 university hospital workers, Park et al. (2020) found that participants reported job stressors such as exposure to and treating patients with COVID-19, working with COVID-19 samples, and negative experiences such as social rejection associated with their jobs. They also found that these stressors were associated with outcomes such as depression and anxiety (Park et al., 2020). Moving forward, future research should pivot towards developing novel stress reduction interventions as well as adapting existing ones to support healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Gdudycha. (n.d.). Symptoms of Stress. Own work. Retrieved February 2, 2021, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:StressSymptoms.gif

McVicar, A. (2003). Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(6), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02853.x

Olson, K., Sinsky, C., Rinne, S. T., Long, T., Vender, R., Mukherjee, S., Bennick, M., & Linzer, M. (2019). Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress and Health, 35(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2849

Park, C., Hwang, J.-M., Jo, S., Bae, S. J., & Sakong, J. (2020). COVID-19 Outbreak and Its Association with Healthcare Workers’ Emotional Stress: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 35(41). https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e372

Sallon, S., Katz-Eisner, D., Yaffe, H., & Bdolah-Abram, T. (2017). Caring for the Caregivers: Results of an Extended, Five-component Stress-reduction Intervention for Hospital Staff. Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2015.1053426

Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal, 16, 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-480

Related Posts

PANDAS––A Self-Destruction of the Mind

Figure 1: PANDAS, characterized by acute neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms,...

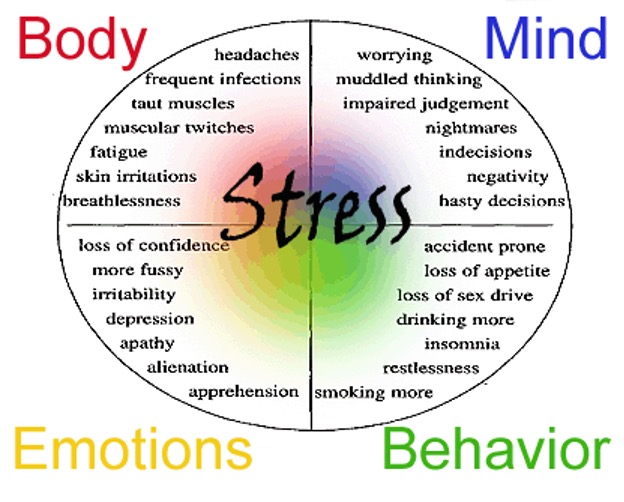

Read MoreAn International Team of Researchers Just Solved One of the Biggest Mysteries About the Human Heart

Figure 1: The heart is one of the most complex...

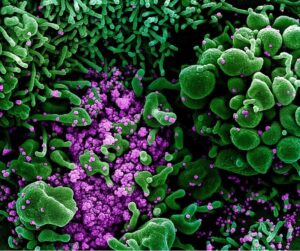

Read MoreThe Immunological and Physiological Effects of SARS-COV-2 on the Human Body

Figure 1: The representation of cellular activity of SARS-COV-2 as...

Read MoreVincent Lai