This article was originally submitted to the Modern MD competition hosted by the Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science (DUJS) and was recognized as an honorable mention.

Abstract

Society has historically relied on the binary division between women and men in nearly all aspects of society, from language and education to public policy and healthcare. Recently, clear distinctions of roles are becoming blurred, but disparities still exist. The terms sex and gender have been often used interchangeably to differentiate between women and men, but it is essential to acknowledge the difference between the concepts. Simply put, while sex refers to biological differences, gender refers to social differences. Gender differences exist in healthcare and clinical knowledge; women have been generally neglected from clinical studies with the exception of a few diseases, and the LGBT population has been ignored in the clinical field(Lapinski et all., 2014). Gender-specific medicine considers gender differences in healthcare in prevention, clinical signs, therapeutic approach, and psychological/social impact. This paper aims to review gender-specific medicine in terms of biological differences, social differences in approaching healthcare, and specific cases of the LGBTQ community, therefore highlighting the importance of gender-specific medicine in healthcare policy. From a biological perspective, different sexes have different physical properties that can impact the efficacy of medical treatment and side effects. Such variations are investigated through the cases of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and Coronavirus Disease 2019. Gender differences in access to healthcare in the social realm arise from different social norms or gender expectations. LGBT populations are often disregarded in health policy and research; while they are exposed to various unique physical and mental health risks as they age, they are at lack of government services or social networks and are more likely to delay or avoid care. Only a gender-inclusive perspective in medical education, medical research, and healthcare policy can properly address the unique needs of each population.

Gender Differences in Health and Medicine and the Importance of Gender-Specific Medicine in Healthcare Policy

Historically, society has relied on the binary division between women and men in nearly all aspects of life, from language and education to public policy and healthcare. The gender equality movement has sprung up relatively recently, as gender equality became part of international human rights by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and the international feminist movement gained recognition in the 1970s (United Nations, n.d.). The clear distinctions of roles and behaviors are becoming increasingly blurred with more women obtaining jobs that used to be done by men, but disparities still exist.

The terms sex and gender have often been used interchangeably to differentiate between men and women. However, it is essential to acknowledge the key difference between the two concepts. Sex refers to the biological differences between males and females in how the body works, due to chromosomal differences which determine differences in bodily features at birth. Gender, on the other hand, refers to the social construct of gender identity and what the individual chooses to identify with. Expectations about gender-related behavior or appearance can change depending on the social, cultural, and historical context (Newman, 2021). Social pressures can encourage people to act according to the gender roles of their assigned sex. In some cultures, politeness and caring are expected in women while strength and competitiveness are expected in men. Simply put, “sex refers to biological differences, whereas gender refers to social differences” (Vlassoff, 2007).

Gender differences exist in clinical knowledge and access to healthcare. Although research specifically on gender differences increased after the women’s health movement of the 1970s, women have been generally neglected from clinical studies except for those regarding the reproductive system. The situation for women has improved compared to the past, as many countries require medical study designs to consider implications on both sexes. However, the LGBT population has been ignored throughout history and awareness levels still remain low other than research on sexually transmitted diseases (DeCola, 2012).

Gender-specific medicine, by one definition, is “the study of how diseases differ between men and women in terms of prevention, clinical signs, therapeutic approach, prognosis, psychological and social impact” (Baggio et al., 2013). Because different gender identities and sexual orientations exist, though the full definition of gender-specific medicine is really more broad than this. It considers additionally factors relating to gender identity other than sex differences between males and females.

This paper aims to review gender-specific medicine by investigating clinical and biological differences, as well as social differences in approaching healthcare. It will also focus in on the specific case of the LGBTQ community, thereby highlighting the importance of gender-specific medicine in healthcare policy.

Literature Review

Biological Determinants

Individuals of different sexes have unique biological properties, including different sex chromosomes, varying concentrations of sex hormones, and a higher percentage of body fat in females than males (Chicago Medical Society, n.d.). These properties can impact clinical treatment and medication; for instance, body size and weight can impact the adequate doses of drugs. Higher levels of fat in females can lead to fat soluble ingredients having more substantial impacts on females even at smaller doses (Gender Medicine, 2013). These clinical differences impact the course of cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), among other illnesses. Those three specifically will be considered.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death globally, accounting for an estimated 31% of all deaths worldwide, with 17.9 million people dying each year (World Health Organization, n.d.). Over three quarters of all deaths from CVD happen in low and middle income countries. Risk factors include unhealthy habits such as a high-cholesterol diet, alcohol and tobacco use, hypertension, and high blood glucose levels (World Health Organization, n.d.).

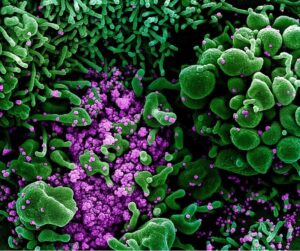

Figure 1: Coronary Artery Disease. (Wikimedia Commons, Blausen.com staff)

Coronary heart disease (CHD), a type of CVD, occurs when the coronary arteries become too narrow and thus cannot supply enough blood to the heart. This commonly occurs because the inner layer of the coronary artery becomes damaged and waste products such as cholesterol collect in the affected area. CHD is one of the most common types of CVD that can lead to heart attack and stroke (Sullivan, 2019).

There has been a decrease in mortality rate for CHD in the last 30 years, but this decrease has not been as pronounced for females as it has been for males, and clinical trials are still being done exclusively on males (Baggio et al., 2013). Although overall incidence of CHD is typically lower in females, females have higher mortality rates and poorer recovery after a cardiovascular event (Gao et al., 2019). CHD in females often goes underrecognized especially at younger ages because symptoms in females are more often atypical. Females have higher resting heart rate, longer QT interval, and increased risk for drug-induced torsades de pointes, meaning that they are at higher risk for stroke than males (Gao et.al, 2019). Low levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL), which absorbs cholesterol and delivers it to the liver, are also associated with high risk of heart attack. HDL levels are higher in younger females than males; however, after menopause, females experience higher levels of cholesterol (Krauss et al., 1979). Cholesterol can form plaques and build up in the arteries, causing high blood pressure and which may contribute to CHD (US National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

Sex differences also manifest in the treatment of CVD. Statins are drugs that can lower cholesterol levels by reducing the liver enzyme that produces cholesterol (Bruce, n.d.). Statins decrease the risks of cardiovascular events and overall mortality in both sexes, but the side effects vary. Minor side effects include headaches or nausea, but more severe effects include myositis and rhabdomyolysis, which involve inflammation and damage to the muscles. The female sex by itself is one of the major risk factors for problems in the muscle tissue (Baggi et.al, 2013). Karalis et al. (2016) found that new or worsening muscle pain symptoms were more frequently reported in females than males, and females are more likely to stop or switch their statin due to muscle symptoms. Sex differences are also evident in β-blocker treatment, which block the effects of adrenaline and slow down heart rate (Beckerman, 2020). CYP2D6, an enzyme expressed in the liver, plays a key role in the metabolism of β-blockers and generally shows higher activity in males than females. Drug toxicity generally appears more frequently in females than in males for the β-blockers propranolol and metoprolol, so females can suffer more from side effects of the drug than males (Oertelt-Prigione, 2009). Both in the expression of diseases and efficacy of drug treatment, males and females show distinct physical reactions.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) involves damage to the kidneys over a long period of time, causing disruptions in basic functions of the kidney such as filtering waste and water out of the blood, producing hormones like vitamin D or erythropoietin, and balancing water, salts and minerals. There is no particular cure for CKD, and progression of CKD can eventually lead to kidney failure and even CVD (NHS, 2019).

Cobo et al. (2016) mentions that “Men and women with CKD differ with regard to the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and its complications […]Yet an approach using gender in the prevention and treatment of CKD, implementation of clinical practice guidelines and in research has been largely neglected.” Various factors lead to sex differences in the progression and symptoms of CKD. For instance, although males have a lower prevalence of CKD, females have overall lower risk of CKD progression and lower mortality rate (Carrero, 2010). This could be due to the different levels of sex hormones, as estrogens have anti-fibrotic and anti-apoptotic effects on the kidney, helping to prevent the progression of CKD. Androgens have proapoptotic and profibrotic properties that can promote the apoptosis, or death, of renal cells (Carrero, 2010). Renal plasma flow and renal blood flow also decrease significantly more in males with increasing age compared to females (Ahmed, 2007).

COVID-19

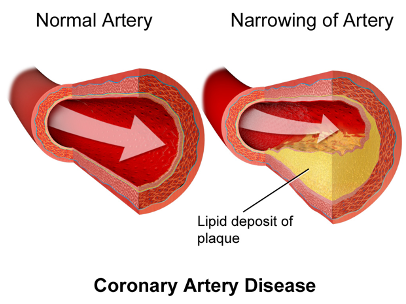

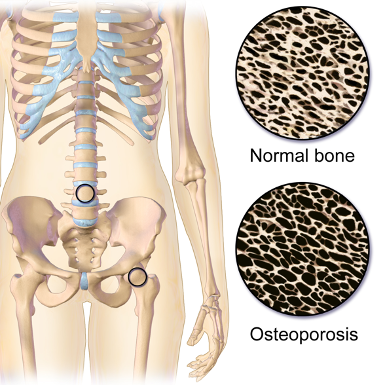

Sex differences exist in the mortality and prevalence of COVID-19 as well. The pandemic broke out in December 2019 and people with pre-existing diseases or symptoms such as hypertension, diabetes, CVD, or obesity have been found to be at higher risk (Zhou et al., 2020). There are noticeable differences between sexes in COVID-19 prevalence, as the male to female ratio of overall cases is 2.7:1 (Wang et al., 2020). Higher severity and mortality is observed in males compared to females regardless of age (Carrero, 2010). One factor may be that females have lower levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which is the entry receptor for the virus in the lungs (Lukassen et al., 2020). Although little gender-based research has been done for COVID-19, it is clear that differences exist and should be factored into research and healthcare policy.

Figure 2: ACE2 receptor and Covid-19. (Davian Ho, Innovative Genomics Institute)

Determinants

Differences in health outcomes – either in treatment-seeking behavior or ability to access healthcare – between gender groups also emerge because of social determinants. For instance, in many developing countries, men seek formal treatment more frequently while women are more likely to self-treat. This is partly due to the lack of education for women and social norms about gender roles, such as childcare duties. Women in developing countries tend to have lower health literacy and often delay modern treatment (Vlassoff, 2007). For chronic diseases, women in societies where they are primarily responsible for childcare, household needs, and aging family members tend to delay prevention or treatment (National Institutes of Health, n.d.). Adolescent boys in lower-middle income countries also tend to be exposed to more unintentional injuries, violence, alcohol, or drugs (Kennedy et.al, 2020). On the other hand, in high-income countries, women tend to take more preventative measures for illnesses and are more likely to seek modern treatment once they are ill. Lower utilization of healthcare services appears in men because of factors like full-time working, less flexible schedules, and long waits for routine care appointments (DeCola, 2012). In regards to mental health, while women are twice as likely to experience mood disorders like depression, women are also more likely to admit their symptoms and seek treatment. This is partly attributable to social circumstances like greater exposure to discrimination or gender violence (Astbury, 2001). Two cases that demonstrate gender differences in health due to social factors will be discussed here: osteoporosis and diabetes.

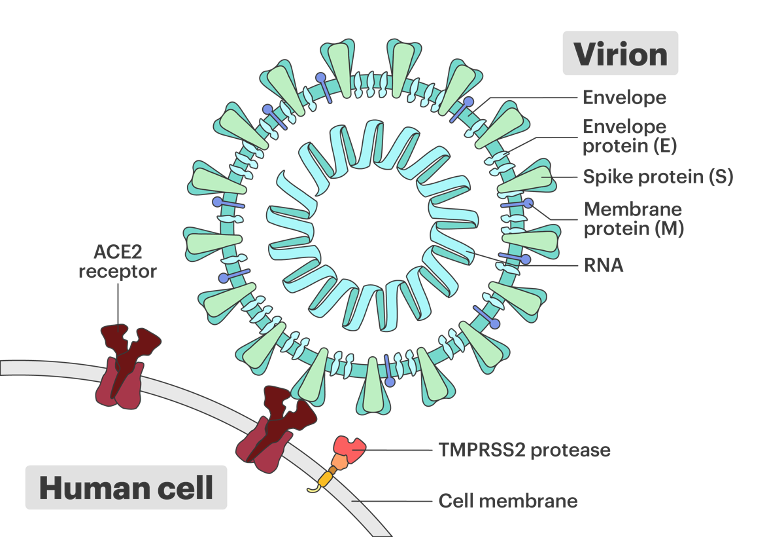

Table 1: Osteoporosis. (Wikimedia Commons, BruceBlaus)

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease marked by a decrease in bone density and bone mass that results in fragility and fractures (Rachner et.al, 2011). Bone density scans such as the DXA scan are used for osteoporosis screening (NHS, 2019). Major risk factors are aging, parental history of hip fracture, smoking, and alcohol intake (Sozen et.al, 2017). Treatment options include prescribing anti-resorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates to maintain bone density and reduce the risk of bone fracture (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017).

In Europe and the United States, approximately 40% of post-menopausal women and 30% of men will experience bone fracture due to osteoporosis at some point in their lives (Reginster & Burlet, 2006). Despite the fact that both men and women are at risk of osteoporosis, the disease has been mislabeled by the public as a “woman’s disease” and is often underrecognized and undertreated in men. Men often have worse outcomes after a major fracture; they are almost twice as likely as women to die after a hip fracture, and the one-year excess mortalit rate after a hip fracture at age 80 years is 18%, while that of women is 8% (Haentjens, 2010).

Awareness about osteoporosis in men remains low. While regular screening for osteoporosis is recommended for the aging population in general, few health-related organizations provide clear screening recommendations for men (Aswalt, 2017). Men are less likely to undergo screening or receive medical treatment, possibly due to older age of onset or lack of insurance coverage (Aswalt & Adler, 2012). A study that included 8262 people of ages eligible for screening found that only 60% of women and 18.4% of men had undergone DXA scanning. Men are also undertreated after diagnosis, partly due to the low awareness of physicians. A study of adults with hip fractures in hospitals in North Carolina found that men are about 75% less likely to receive osteoporosis treatment during their hospital stay than women. Another study of a Texas hospital found that 27% of men, compared to 71% of women, reported receiving treatment one year after a fracture (Kiebzak et al., 2002).

Diabetes

Diabetes Mellitus is a group of chronic diseases that result from anomalies in insulin secretion or insulin effet that can potentially lead to renal failure, loss of vision, or CVD. Type 1 diabetes accounts for about 5-10% of cases and results from the destruction of β-cells of the pancreas by the immune system. Type 2 diabetes accounts for approximately 90~95% of cases and often occurs in adults with insulin resistance that does not stem from the autoimmune destruction of β-cells. It is well-established that obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes (American Diabetes Association, 2005).

Diabetes is one of the most psychologically demanding chronic disorders as there is no cure, and patients have to change their life habits to control it. The disease is overall more prevalent in men than in women, but different social factors impact the disease (Siddiqui et al., 2013). For instance, women have stronger associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and abdominal obesity and physical activity linked to diabetes (Rathmann et al., 2005). A survey in Canada found that SES variables such as low household income and food insecurity are related to a higher risk of diabetes in women but not in men (Rivera et al., 2015) Women tend to be more impacted by social factors such as education or occupation when predicting future risks of diabetes. Moderate alcohol consumption can increase adiponectin levels, improve insulin sensitivity, and reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes specifically in women (Kautzky-Willer et al., 2016).

Furthermore, women with diabetes have to deal with other psychological stressors that may impact health outcomes. Stress could come from unpaid housework and responsibilities within the family and discrimination (Siddiqui et al., 2013). Some argue that the differences stem from traditional gender roles where women have greater responsibilities for family health; one may not be willing to change her family’s lifestyle to meet her health needs and experience stress from conflicting demands. Men and women also show different attitudes towards the disease, as women tend to use diabetes services more once they perceive symptoms (Kautzky-Walter, 2016).

Considering the LGBTQ Community

Little has been done to consider the LGBTQ community in health policy and research. While many countries recommend medical studies to consider both males and females, gender/sexually diverse people are often excluded. Barriers that they face in all aspects include heterosexism, the belief that heterosexuality is the standard and superior to all other forms of sexuality, and cis-genderism, a strict binary perspective on gender (Mule et al., 2009).

The Ministerial Advisory Committee on Gay and Lesbian Health for the State of Victoria, Australia characterized how social factors such as violence, discrimination, social invisibility, self-denial, and internalized phobia could result in health impacts like alcohol and drug use and high risk of depression and suicide. The population has a higher risk of suffering violence than the general population, as rougly 25 to 33% of the LGBTQ individuals in the USA reported experiencing a violent act. Bisexual men and women in Canada earn 30% and 15% less respectively than heterosexual individuals. LGBTQ Youth more commonly flee from or are expelled from abusive homes, resulting in higher rates of homelessness (Mule et al., 2009).

Healthcare practiceoften excludes sexually diverse experiences and discourages the free disclosure of gender/sexual identity. LGBTQ individuals are less likely to utilize healthcare systems and have health insurance, conceivably because healthcare professionals have limited knowledge and unintended biases. For instance, many physicians may have a lack of knowledge when treating trans patients, or alternatively, overemphasize trans status in mental evaluations (Snelgrove et al., 2012). As a consequence, transgender, bisexual, and intersex individuals are the least likely to seek preventive healthcare. While LGBT populations are exposed to various physical and mental health risks, they are at a lack of government services and social networks, and are more likely to avoid or delay care due to lack of insurance or general healthcare providers while having less social support(LGBTQ+ Health Disparities | Cigna, n.d.).

Conclusion

Individuals off different genders experience and react to disease differently. Gender is also impacted by other social determinants of health such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and ability (Gender and Determinants of Health, n.d.). To make sure that everyone has access to healthcare that fits them, it is important to consider gender in health policy. In terms of medical education, gender biases that often set men as the norm or reference point and explain that “men and women are basically the same,” should be removed. An inclusive medical curriculum can improve the lack of knowledge and awareness of physicians. Gender medicine can also be considered in medical research, by including men, women, and non-binary subjects in clinical studies (United Nations, n.d.). One could draw inspiration from the proposed health model of Machulf et.al (2020), which emphasizes (1) investigation of gender-specific medical profiles for all diseases, (2) interrogates the dynamics of gender disparities across developmental stages, and (3) considers additional risk factors like socio-demographic factors or lifestyle habits. Only by strengthening gender-inclusive perspectives in medical education, medical research, and healthcare policy can society properly address the unique needs of each segment of the population and reduce inequalities.

References

Ahmed, S. B., Fisher, N. D. L., & Hollenberg, N. K. (2007). Gender and the renal nitric oxide synthase system in healthy humans. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2(5), 926–931. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.00110107

Alswat, K. A. (2017). Gender disparities in osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 9(5), 382–387. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2970w

Alswat, K., & Adler, S. M. (2012). Gender differences in osteoporosis screening: retrospective analysis. Archives of Osteoporosis, 7(1-2), 311–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-012-0113-0

American Diabetes Association. (2005). Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. In Diabetes care (Vol. 28, pp. 537–542). essay, American Diabetes Association.

Astbury, J. (2001). Gender disparities in mental health. Ministerial Round Tables. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/242.pdf.

Baggio, G., Corsini, A., Floreani, A., Giannini, S., & Zagonel, V. (2013). Gender medicine: a task for the third millennium. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 51(4). https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2012-0849

Beckerman, J. (2020). Beta-Blocker medications for heart disease treatment. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/guide/beta-blocker-therapy.

Bruce, D. F. (n.d.). Statins side effects: pain, inflammation, and more. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/cholesterol-management/side-effects-of-statin-drugs

Carrero, J. J. (2010). Gender Differences in Chronic Kidney Disease: Underpinnings and Therapeutic Implications. Kidney and Blood Pressure Research, 33(5), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1159/000320389

Cobo, G., Hecking, M., Port, F. K., Exner, I., Lindholm, B., Stenvinkel, P., & Carrero, J. J. (2016). Sex and gender differences in chronic kidney disease: progression to end-stage renal disease and haemodialysis. Clinical Science, 130(14), 1147–1163. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20160047

DeCola, P. R. (2012). Gender effects on health and healthcare. Handbook of Clinical Gender Medicine, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336316

Gao, Z., Chen, Z., Sun, A., & Deng, X. (2019, December 20). Gender differences in cardiovascular disease. Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590093519300256

Gender and Determinants of Health. Centre for Gender and Global Health. (n.d.). http://www.ighgc.org/gender-and-determinants-of-health

Gender medicine. in. (2013, December 19). https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/gender-medicine.html

Haentjens, P. (2010). Meta-analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Annals of Internal Medicine, 152(6), 380. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008

Karalis, D. G., Wild, R. A., Maki, K. C., Gaskins, R., Jacobson, T. A., Sponseller, C. A., & Cohen, J. D. (2016). Gender differences in side effects and attitudes regarding statin use in the understanding statin use in America and gaps in patient education (USAGE) study. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 10(4), 833–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.016

Krehely, J. (2009, December 21). How to Close the LGBT Health Disparities Gap. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/

Kautzky-Willer, A., Harreiter, J., & Pacini, G. (2016). Sex and gender differences in risk, pathophysiology and complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine Reviews, 37(3), 278–316. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1137

Kennedy, E., Binder, G., Humphries-Waa, K., Tidhar, T., Cini, K., Comrie-Thomson, L., Vaughan, C., Francis, K., Scott, N., Wulan, N., Patton, G., & Azzopardi, P. (2020). Gender inequalities in health and wellbeing across the first two decades of life: an analysis of 40 low-income and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The Lancet Global Health, 8(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30354-5

Khosla, S., & Hofbauer, L. C. (2017). Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 5(11), 898–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30188-2

Kiebzak, G. M., Beinart, G. A., Perser, K., Ambrose, C. G., Siff, S. J., & Heggeness, M. H. (2002). Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(19), 2217. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.19.2217

Krauss, R. M., Lindgren, F. T., Wingerd, J., Bradley, D. D., & Ramcharan, S. (1979). Effects of estrogens and progestins on high density lipoproteins. Lipids, 14(1), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02533579

Lapinski, J., Sexton, P., & Baker, L. (2014). Acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients, attitudes about their treatment, and related medical knowledge among osteopathic medical students. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 114(10), 788-796.

LGBTQ+ Health Disparities | Cigna. (n.d.). Cigna. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://www.cigna.com/individuals-families/health-wellness/lgbt-disparities

Lukassen, S., Chua, R. L., Trefzer, T., Kahn, N. C., Schneider, M. A., Muley, T., Winter, H., Meister, M., Veith, C., Boots, A. W., Hennig, B. P., Kreuter, M., Conrad, C., & Eils, R. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells. The EMBO Journal. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2020105114

Machluf, Y., Chaiter, Y., & Tal, O. (2020). Gender medicine: Lessons from COVID-19 and other medical conditions for designing health policy. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 8(17), 3645–3668. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3645

Mule, N. J., Ross, L. E., Deeprose, B., Jackson, B. E., Daley, A., Travers, A., & Moore, D. (2009). Promoting LGBT health and wellbeing through inclusive policy development. International Journal for Equity in Health, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-18

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). How SEX and GENDER influence health and disease. National Institutes of Health .

Newman, T. (2021, May 11). Sex and gender: Meanings, definition, identity, and expression. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/232363

NHS. (2019). Osteoporosis. NHS Choices. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis/.

NHS. (2019, August). Overview -Chronic kidney disease. NHS Choices. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/kidney-disease/

Oertelt-Prigione, S., & Regitz-Zagrosek, V. (2009). Gender aspects in cardiovascular pharmacology. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research, 2(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-009-9114-9

Rachner, T. D., Khosla, S., & Hofbauer, L. C. (2011). Osteoporosis: now and the future. The Lancet, 377(9773), 1276–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62349-5

Rathmann, W., Haastert, B., Icks, A., Giani, G., Holle, R., Meisinger, C., & Mielck, A. (2005). Sex differences in the associations of socioeconomic status with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the elderly population: the KORA Survey 2000. European Journal of Public Health, 15(6), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cki037

Reginster, J.-Y., & Burlet, N. (2006). Osteoporosis: A still increasing prevalence. Bone, 38(2), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.024

Rivera, L. A., Lebenbaum, M., & Rosella, L. C. (2015). The influence of socioeconomic status on future risk for developing Type 2 diabetes in the Canadian population between 2011 and 2022: differential associations by sex. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0245-0

Siddiqui, M., Khan, M., & Carline, T. (2013). Gender differences in living with Diabetes Mellitus. Materia Socio Medica, 25(2), 140. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2013.25.140-142

Snelgrove, J. W., Jasudavisius, A. M., Rowe, B. W., Head, E. M., & Bauer, G. R. (2012). “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-110

Sozen, T., Ozisik, L., & Calik Basaran, N. (2017). An overview and management of osteoporosis. European Journal of Rheumatology, 4(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048

Sullivan, D. (2019). Coronary heart disease: causes, symptoms, and treatment. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/184130.

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2021, May 20). Cholesterol. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/cholesterol.html

United Nations. (n.d.). Gender equality. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/gender-equality

United Nations. (n.d.). Integrating the gender perspective in medical and health education and research. United Nations. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/integrate.htm

Vlassoff, C. (2007, March). Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3013263/

Wang, C., Horby, P. W., Hayden, F. G., & Gao, G. F. (2020). A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet, 395(10223), 470–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30185-9

What is Gender Medicine? What is Gender Medicine? – Chicago Medical Society. (n.d.). http://www.cmsdocs.org/news/what-is-gender-medicine

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Cardiovascular diseases. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases/#tab=tab_1

Zhou, F., Yu, T., Du, R., Fan, G., Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Xiang, J., Wang, Y., Song, B., Gu, X., Guan, L., Wei, Y., Li, H., Wu, X., Xu, J., Tu, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., & Cao, B. (2020). Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet, 395(10229), 1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

Related Posts

The Positives of Plushies: Stuffed Animals Have Benefits for Children and Adults

Figure: A young girl sleeps with a teddy bear in...

Read MoreThe Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis May Be the Missing Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa

Figure 1: The microbiota-gut-brain axis is a bidirectional pathway of...

Read MoreAn Introduction to the Ebola Virus

Cover Image: Blood sample of a patient infected by the...

Read MoreThe Biochemistry and Broad Utility of Pfizer’s New COVID-19 Drug: Paxlovid

A photo of a Pfizer facility in Italy. (Image Source:...

Read MoreAre We Driving Our Dogs Sick Through Our Urban Lifestyles?

Figure 1: Allergic disorders in humans and dogs are associated...

Read MoreThe Immunological and Physiological Effects of SARS-COV-2 on the Human Body

Figure 1: The representation of cellular activity of SARS-COV-2 as...

Read MoreJY