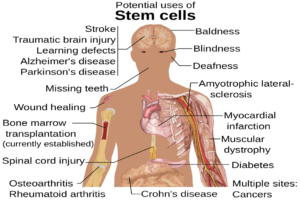

Figure 1: Guards in prisons are able to put prisoners in shackles whenever they see fit – for pregnant women giving birth, shackling can result in severe complications

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Pregnancy can come with several complications for the mother, including high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia (“common complications of pregnancy,” n.d.). In addition, pregnancy and childbirth can be fatal to the mother due to extreme bleeding, infection, unsafe abortion, and obstructed labor. About 810 women die every single day from pregnancy and childbirth related complications worldwide. (“Maternal health,” n.d.). Thus, access to proper prenatal and postnatal health is of vital importance. However, access to healthcare, especially in the US, is extremely variable due to a variety of factors, including employment status, ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic class, and disability status. At the same time, individuals marginalized by these same factors are often at greater risk to enter the prison system. They are at the mercy of the prison healthcare system, which has failed to provide adequate healthcare to prisoners (National Academies of Sciences, 2017; Wilper et al., 2019).

Discussion of the failings of the American carceral system for pregnant women is critically important. Over the last 50 years, the number of women imprisoned has increased eight times over; in 2019, there were over 222,000 women in an American correctional facility (Clarke & Simon, 2013; “Incarcerated Women and Girls,” n.d.). Of these, the majority are of reproductive age. Annually, pregnant incarcerated women give birth to about 2000 babies across the United States. Prisons, which are historically a male-centered institution, fail to meet the mental, physical, and reproductive healthcare requirements of their female inmates (Clarke & Simon, 2013).

Pregnancy is handled especially poorly by prison medics and standards of prenatal care are varied. Prisons are not required to change a pregnant woman’s diet, work requirements, or exercise opportunities, all of which are critical to maintaining the health of both the fetus and the mother (“Pregnant, in prison and facing health risks,” n.d.). During childbirth, more problems arise. Only about 15% of incarcerated women are in federal prisons, where they are protected by anti-shackling laws that prohibit the shackling of pregnant women during childbirth. The other 85%, who are in state or county facilities, remain unprotected and are often bound while giving birth (Sawyer & Wagner, 2020). This causes increased risk of injury and placental abruption, can delay labor progress, can delay medical intervention in the case of emergency, and can prevent administration of epidurals (“Shackling of Pregnant Women in Jails,” 2020). In many cases, the mother and infant are separated almost immediately after birth, which results in psychological trauma for both – there is an increased risk that mothers reoffend, and infants are more likely to develop emotional and behavioral problems later in life (Clarke & Simon, 2013).

Though all pregnant women in prison must contend with these issues, other factors can provoke further violence committed against them. Though there is little demographic information available on prison pregnancies, it is known that racial discrimination plays a significant role in the level of care experienced by pregnant women. One tragic example of violent discriminatory practices is shackling, which is endemic in many correctional facilities. The practice is known to be particularly harmful for Black prisoners, who are faced with not only the oppression of the carceral system but also must suffer systemic racism stemming from the history of slavery in the US. Historically, as the population of Black women in prisons grew in the South, they were labeled by prison guards as dangerous – in turn, during pregnancy, they began to be shackled (Ocen, 2012). Though the practice has since spread to women of all races, it is disproportionately impactful for Black women, who are imprisoned two times more than White women (Sufrin et al., 2019).

In addition to shackling, it is known that Black women endure significantly higher rates of preterm birth than women of other races in prison after accounting for differences in incarceration incidences by race (Dyer et al., 2019). Preterm birth can have several consequences for both the infant and the mother. For example, preterm births for infants can cause short-term issues with breathing, hypotension, intraventricular hemorrhage, and a weakened immune system. There are also several issues that may occur in the long term, including, but not limited to, development of cerebral palsy, impaired learning, and developmental delays (“Premature birth—Symptoms and causes,” n.d.). On the other hand, compared to mothers who give birth on time, mothers who give birth prematurely are more at risk for developing several health problems, such as anxiety, fatigue, and flashbacks; they are also more likely to have negative feelings about their baby (Henderson et al., 2016).

It is evident that there are problems with prison healthcare systems’ treatment of pregnant women prepartum, during childbirth, and postpartum. One possible avenue for improving the conditions for both mothers and infants is the development of prison nursery programs, which would give infants many educational opportunities while allowing them to remain close to their mothers during their stay in prison. Having high quality prison nurseries has been shown to promote infant development and reduce the chance that the mother reoffends later in life (“Pregnant, in prison and facing health risks,” n.d.). Truly reforming the carceral healthcare system, however, is an even more complex issue. The pervasive problems in prison healthcare are not just due to incarceration status but also to factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality – they are problems that exist at the institutional level and will not be easily solved without dedicated governmental funding towards prison reform. As a start, legislative change at the local, state, and federal level is necessary. Perhaps in the future, Americans can begin to change the overall American prison system and, in the process, give prisoners access to fair and adequate healthcare treatment.

References

Clarke, J. G., & Simon, R. E. (2013). Shackling and Separation: Motherhood in Prison. AMA Journal of Ethics, 15(9), 779–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.9.pfor2-1309.

Dyer, L., Hardeman, R., Vilda, D., Theall, K., & Wallace, M. (2019). Mass incarceration and public health: The association between black jail incarceration and adverse birth outcomes among black women in Louisiana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2690-z

Henderson, J., Carson, C., & Redshaw, M. (2016). Impact of preterm birth on maternal well-being and women’s perceptions of their baby: A population-based survey. BMJ Open, 6(10), e012676. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012676

Incarcerated Women and Girls. (n.d.). The Sentencing Project. Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarcerated-women-and-girls/

Maternal health. (n.d.). Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/maternal-health

National Academies of Sciences (2017). The State of Health Disparities in the United States. In Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/

Ocen, P. (2012). Punishing Pregnancy: Race, Incarceration, and the Shackling of Pregnant Prisoners. California Law Review, 100(5), 1239-1311. Retrieved December 31, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23408737

Premature birth—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved December 31, 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/premature-birth/symptoms-causes/syc-20376730

Pregnant, in prison and facing health risks: Prenatal care for incarcerated women. (n.d.). Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/pregnant-in-prison-and-facing-health-risks-prenatal-care-for-incarcerated-women-45034

Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2020). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020. The Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html

Shackling of Pregnant Women in Jails and Prisons Continues in the United States. (2020, January 29). Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/news/shackling-of-pregnant-women-in-jails-and-prisons-continues/

Sufrin, C., Beal, L., Clarke, J., Jones, R., & Mosher, W. D. (2019). Pregnancy Outcomes in US Prisons, 2016–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006

What are some common complications of pregnancy? (n.d.). National Institutes of Health. Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pregnancy/conditioninfo/complications

Wilper, A. P., Woolhandler, S., Boyd, J. W., Lasser, K. E., McCormick, D., Bor, D. H., & Himmelstein, D. U. (2009). The Health and Health Care of US Prisoners: Results of a Nationwide Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 99(4), 666–672. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279

Related Posts

Cranial Cartography: A New Method for Visualizing Blood Vessels and Stem Cells in the Skull

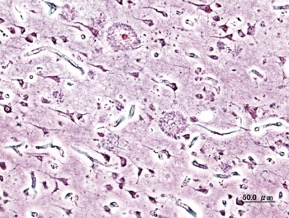

The diagram above displays the many potential uses of stem...

Read MoreExploring Possibilities for the Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

Figure 1: Extracellular deposits of amyloid-beta proteins as seen in...

Read MoreNew Study Finds that Media Multitasking Impairs Memory in Young Adults

Figure 1: Engaging with multiple types of digital media simultaneously,...

Read MoreAnahita Kodali

Comments are closed.