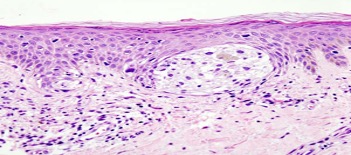

Cover Image: Melanoma in a skin biopsy with H&E stain.. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, KGH)

Melanomas, like most cancers, result from genetic mutations that effect cell cycle proteins, causing uncontrollable cell replication. These mutations can occur as a cell is replicating and differentiating from pluripotent cell lineages into more specialized forms. In melanomas, the onset of a neoplasm might occur in the neural crest cells, which are precursors of melanoblasts that, in turn, give rise to melanocytes (skin cells that produce the sun-blocking pigment melanin). Susceptibility to cancer at either of these cellular stages – neural crest cell differentiation to melanoblasts, melanoblast differentiation to melanocytes – has been termed ‘oncogenic competence’, and it is distinctively varied across each of the stages (Haigis et al., 2019).

In a landmark paper, Baggiolini et. al. set out to quantify the influence that chromosomal packing has on oncogenic competence in each cell type – their theory being that the degree to which DNA is tightly wound around chromosomal proteins impacts the expression of genes, and that different cell types regulate chromosomal packing differently (thus leading to variations in ‘oncogenic competence’)

Initially, the researchers used a zebra fish transgenic model (experimental animal models whose genomes have been artificially altered through introduction of DNA sequences from other species) .In this experiment, the melanoma model was a zebrafish in with the human BRAFV600E oncogene. The zebrafish expresses the crestin gene embryonically in neural crest progenitors (NCPs) and is specifically re-expressed only in melanoma tumors, making it an ideal candidate for tracking melanoma from initiation onward. Fish that expressed BRAFV600E in either the neural crest cells or the melanoblasts developed aggressive tumors. Those in the melanocyte stage failed to develop tumors and instead developed small patches of nevus-like cells. These data suggested that competence to respond to BRAFV600E is biased toward cells of origin that exhibit progenitor gene programs and that those programs allow for formation of distinct tumors.

The success of this experiment encouraged the researchers to try and replicate the results in a human pluripotential stem cell model. The stem cells were guided to develop into the melanocyte lineage. In both cases, the researchers found that the BRAFV600E missense mutation (where the amino acid valine is exchanged for glutamic acid) was associated with melanomas. Also, transcription factors such as the Sox10. mitfa, and tyrp1 were across three cell states: neural crest, melanoblast, and melanocyte stages, respectively (Kaufman et al., 2016; Kunz, 2014; Shakhova et al., 2012).

Moreover, the researchers determined that ATAD2 expression is sufficient to endow melanocytes with intrinsic oncogenic competence. The exact mechanism of this transition of melanocytes to a more oncogenic state involves a protein complex formed between SOX10 and ATAD2 that facilitates transcription of the oncogene BRAFV600E though MAPK signalling (Ciró et al., 2009).

A better understanding of the genesis and progress of cancer in different cell lineages will play a vital role in promoting the development of patient-specific therapies by identifying new targets for cancer therapies. In the case of melanoma, these targets could potentially be oncogenes like BRAF, transcription factors like Sox10, or chromatin-associated factors such as ATAD2 (Baggiolini et al., n.d.).

References

- Baggiolini, A., Callahan, S. J., Montal, E., Weiss, J. M., Trieu, T., Tagore, M. M., Tischfield, S. E., Walsh, R. M., Suresh, S., Fan, Y., Campbell, N. R., Perlee, S. C., Saurat, N., Hunter, M. V., Simon-Vermot, T., Huang, T.-H., Ma, Y., Hollmann, T., Tickoo, S. K., … White, R. M. (n.d.). Developmental chromatin programs determine oncogenic competence in melanoma. Science, 373(6559), eabc1048. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc1048

- Ciró, M., Prosperini, E., Quarto, M., Grazini, U., Walfridsson, J., McBlane, F., Nucifero, P., Pacchiana, G., Capra, M., Christensen, J., & Helin, K. (2009). ATAD2 is a novel cofactor for MYC, overexpressed and amplified in aggressive tumors. Cancer Research, 69(21), 8491–8498. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2131

- Haigis, K. M., Cichowski, K., & Elledge, S. J. (2019). Tissue-specificity in cancer: The rule, not the exception. Science. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.aaw3472

- Kaufman, C. K., Mosimann, C., Fan, Z. P., Yang, S., Thomas, A. J., Ablain, J., Tan, J. L., Fogley, R. D., van Rooijen, E., Hagedorn, E. J., Ciarlo, C., White, R. M., Matos, D. A., Puller, A.-C., Santoriello, C., Liao, E. C., Young, R. A., & Zon, L. I. (2016). A zebrafish melanoma model reveals emergence of neural crest identity during melanoma initiation. Science, 351(6272), aad2197. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2197

- Kunz, M. (2014). Oncogenes in melanoma: An update. European Journal of Cell Biology, 93(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.12.002

- Malignant_melanoma_(1)_at_thigh_Case_01.jpg (600×452). (n.d.). Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6b/Malignant_melanoma_%281%29_at_thigh_Case_01.jpg

- Shakhova, O., Zingg, D., Schaefer, S. M., Hari, L., Civenni, G., Blunschi, J., Claudinot, S., Okoniewski, M., Beermann, F., Mihic-Probst, D., Moch, H., Wegner, M., Dummer, R., Barrandon, Y., Cinelli, P., & Sommer, L. (2012). Sox10 promotes the formation and maintenance of giant congenital naevi and melanoma. Nature Cell Biology, 14(8), 882–890. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2535

Related Posts

Another Option for Pre-Exposure HIV Prevention for Women

Figure 1: A symbol of the organization UN woman, an...

Read MoreThe Gut May Be The Door to Effective Depression Treatment

First Author: Jillian Troth1 Co-Authors [Alphabetical Order]: Roxanna Attar2, Caroline...

Read MoreCalling All CARs: Redesigning CAR-T Cancer Immunotherapy

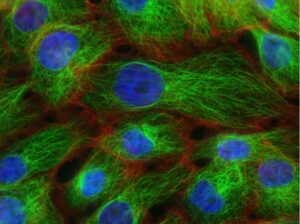

Figure 1: This image displays microtubules – green fibre-like structures...

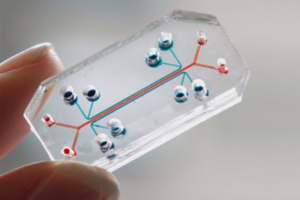

Read MoreAdvancements in Regenerative Medicine – Unleashing the Potential of Artificial Organs and Organs-on-a-Chip

Source: 허동은교수, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 Introduction Recent years...

Read MoreUncovering (Ant)imicrobial Agents in Insects

Figure 1: Insect microbiomes offer a promising source for the...

Read MoreBispecific Antibody Recruits Vγ9+ γδ T cells for Leukemia Treatment

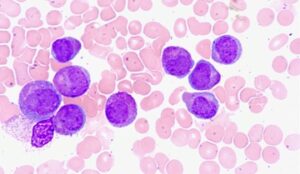

Figure 1: The image is taken from an elderly woman...

Read MoreWhitney Nicanor Mabwi