Taking the proper, science-backed steps could help prevent the next pandemic. (Source: Unsplash, Alin Luna)

Abstract

Covid-19, caused by the SARS-CoV2 virus, has infected hundreds of millions of people worldwide and caused millions of deaths World Health Organization, 2022). The unprecedented pandemic has caused lasting impacts on individual lives, the economy, politics, and society, as the world was unprepared for its outbreak. In order to control transmissions, governments have implemented mask wearing and contact tracing policies and suggested vaccination. Experts agree that the next pandemic is very likely to happen within the next 25 years, and there has to be some change to public health policies to be fully prepared for the next pandemic (Center for Global Development, n.d.). Pre-pandemic preparatory advice includes: repairing healthcare systems to serve all, but particularly, marginalized populations, investment in public hygiene and sanitation, achieving flexibility with online platforms, supporting telecommunication technology, developing a culture where mask-wearing is socially acceptable even for healthy people, and developing a contact-tracing app that can be introduced nation-wide in case of a pandemic. Once there is a viral outbreak, it is important to identify the origins and characteristics of the virus, and to develop quick and accurate test methods. This paper aims to provide recommendations and guidelines about how to prepare for and respond to the next pandemic.

Introduction

It is predicted that a pandemic of equal or greater magnitude than Covid-19 is likely to occur in the next 25 years (Center for Global Development, n.d.). It is important for the government to integrate preliminary measures in public health to decrease the magnitude of harm as part of the “new normal.” Coronavirus Disease 2019, or Covid-19, is a highly infectious disease that broke out in late 2019. While it is known that the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the causative agent for COVID-19, originated in China in December 2019 and had spread globally by January 2020, evidence suggests that the disease first emerged between early October and mid-November (Klein & Flanagan, 2016; Roberts et al., 2021). As of December 2021, the cumulative number of confirmed cases globally reached more than 280 million, and the total death count had reached 5 million. (World Health Organization, 2022) The virus is known to be highly similar to bat SARS-like coronaviruses, which are strains of SARS-related viruses isolated from Chinese horseshoe bats (European Union External Action, 2021). This led many experts to hypothesize that bats are the reservoir host, but whether the origin is a natural zoonotic spillover or an accidental release from a lab is yet undetermined, and presently there is not enough evidence to confirm either theory (Sills et al., 2021). Transparent, objective, and data-driven investigation about the origins of the virus is crucial for responding to and preventing future viral outbreaks; therefore, many countries and experts agree that clarity about the origins of the virus is necessary (European Union External Action, 2021). Although many people with the disease experience only mild to moderate symptoms and recover without requiring special treatment, some cases result in severe illness requiring intensive medical attention. Main symptoms include fever (83%), cough (82%), and shortness of breath (31%) sometimes accompanied by additional symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or nausea (Ciotti et al., 2020). Damage is primarily done to the lungs, but the disease may also lead to cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, kidney, liver, central nervous system, and ocular damage that can persist long after the initial infection. Transmission happens mainly through the respiratory route via droplet transmission, and on average it takes 5-6 days (and sometimes up to 14 days) for symptoms to show after a person is infected (World Health Organization, n.d.).

Impacts of Covid-19

Because of its rapid spread, Covid-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11th 2020, and as nations and communities were unprepared for a public health crisis of such magnitude, immediate impacts followed (World Health Organization, 2020b). The UN framework for the immediate socio-economic response to Covid-19, issued April 2020, stated that the pandemic “is far more than a health crisis; it is affecting societies and economies at their core.” As such, socio-economic spillover effects of the pandemic in many aspects made it more than just a health crisis. Fear of mass infection arose as a new driving factor in decision-making across all levels, leading not only to individuals prophylactically limiting human interactions, but also governments enforcing urgent measures such as closing down public facilities and lockdowns. Everyone was impacted by the pandemic on individual, social and national levels, but those with low incomes and limited access to technologies like internet connection were disproportionately impacted (Delechat & Medina, 2020).

Impacts on Daily Life

Social distancing measures and closure of various facilities including schools, places for entertainment, hotels, restaurants, and religious places has led to countless changes in normal life (Haleem et al., 2020). Many workers have lost their jobs or have experienced severe decreases in income. Also, school closures due to Covid-19 have been shown to have negative impacts on student achievement, especially on younger students and students from families of lower socio-economic status who are less likely to have access to remote learning (Hammerstein et al., 2021).

The pandemic has also had negative impacts on general mental health. A KFF tracking poll published in February 2021 indicated overall increased shares of adults reporting symptoms of anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder during the pandemic in January 2021 (41.4%) compared to prior to the pandemic (11.0%). Factors that contribute to such changes include prohibition of large gatherings, closure of various facilities, social isolation, limited access to mental health care, job loss and income insecurity, as well as poor physical health (Garfield, 2021).

Economic impacts

Immediate impacts of Covid-19 on national and international economies were devastating. As of April 2020, the International Labor Organization announced that about 1.6 billion workers, nearly half of the global workforce, were severely impacted by the pandemic and in danger of having their livelihoods destroyed (International Labour organization, 2020). The unemployment rate in the United States reached a peak of 14.8%, the highest since the beginning of official data collection in 1948 (Gene et al., 2021). The United States declared an economic recession in February 2020. In June 2020, the World Bank called the situation the deepest recession since World War Two (Bank, 2020).

Job losses, lower incomes, increased poverty, and limited human gatherings have led to interruptions and loss of productivity, de-skilling associated with prolonged unemployment, along with missed opportunities to build human capital and create connections. According to human capital theory, education and skill training can increase productive capacity and improve labor market outcomes. During an economic crisis, earnings of those with less education and training fall because of increased unemployment, and workers in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing are most affected (Tazeen, 2020). Many sectors have also suffered from supply chain disruption as production in areas with high case numbers is impossible, and supply chains could collapse easily if a single supplier in a single country is unable to produce a critical and widely used product. For instance, car manufacturers in Europe were strongly impacted when a single manufacturer, MTA Advanced Automotive Solutions, was forced to close down one of its plants in Italy due to Covid-19.

In the US, The economy has slowly recovered since the initial disruption, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts that real GDP will grow and exceed its sustainable level by 2.5% by mid-2022. The International Monetary Fund estimated that economic growth last year was 5.9%, with smaller improvements among developing countries. Yet, hurdles such as the new variants of Covid-19 and rapid inflation exist (Wolf, 2022). The harm experienced by developing economies and sectors such as service-providing businesses and travel has led to development levels far below expected levels in the absence of the pandemic, and recovery is projected to be uneven among different socio-economic groups. (Edelberg, 2021)

Impacts on politics/international relations

Following the experience with the limitations of single source supply chains and shortages in the supply of many materials, there may be general shifts in global politics and international markets. Especially during the early stages of the pandemic, countries suffered from shortage of masks and medical supplies. Even before the pandemic outbreak, Chinese manufacturers were responsible for the production of half of the world’s medical mask supply, and when Covid-19 started to spread, the Chinese government effectively stockpiled the Chinese mask supply while importing masks from abroad, resulting in a supply crunch in other countries. Russia, Turkey, and Germany also prohibited the export of medical masks to meet domestic demand (Henry, 2020). Likewise, the United States halted the trading of masks made by the US company 3M to Canada and Latin America (Politico, 2020). Countries retreated from globalization by diverting medical supplies to themselves and blocking exports, despite causing harm to allies and neighboring countries. Such breaches in long-term relationships may extend to international business diplomacy where countries can easily break bonds when facing similar crises (Henry, 2020).

Possibility of the Next Pandemic

Historically, the risk of pandemics has often been underestimated; as a result, many countries were not able to respond effectively to the outbreak of Covid-19. An analysis conducted by a team at the company Metabiota showed thorugh historical modeling that the frequency and severity of epidemics are increasing, and that this increase is particularly driven by human activities and their impacts on the environment. The probability of future zoonotic spillover events, possible to result in a pandemic of Covid-19 magnitude or larger, is 2.5-3.3% annually, meaning that at the high end there is an estimated 57% chance for such an outbreak to happen in the next 25 years according to research models. (Center for Global Development, n.d.)

In the case of such an outbreak, it is likely that low-income countries and countries that are less equipped to respond will be disproportionately affected by the infectious disease, similar to what happened with Covid-19. Even before Covid-19, researchers identified trends in zoonotic diseases and suggested the strengthening of public health surveillance and early identification/prevention. For instance, a case of a new human coronavirus respiratory disease from Saudi Arabia and novel haemorrhagic fever in Africa that did not grow to worldwide epidemics. (Morse et al., 2012)

Preparation

In order to prepare for the next pandemic and reduce the likelihood of its transmission, governments have to invest in public healthcare systems to respond once an outbreak occurs and pay particular attention to vulnerable populations. These investments are beneficial because they increase access to care (such as testing and vaccination) for all people and reduce the likelihood of viral transmission. Though the government can play a role, personal hygiene and sanitation are essential components of controlling Covid-19 spread as well. In terms of preparing for the socio-economic spillover effects of the pandemic, flexibility for various organizations and operations need to be achieved. Facing Covid-19, it became difficult to hold large in-person gatherings or regular large-scale meetings at work, and during periods with high case numbers, workplaces often had to close down. Many companies and schools turned to online platforms to enable communication between members and continue operations (McKinsey & Company, 2020; Sriam, 2021). Therefore, companies, organizations and schools should develop greater flexibility to switch between offline to online platforms and train employees/teachers/students to use these platforms, which will increase productivity during times of remote work.

Policy Recommendations

Research about the disease

When there is an outbreak, the first thing for public health officials and governments to do is to identify the basic characteristics of the disease and its associated pathogen, including:

- Infectiousness of the disease

- Transmission route

- Incubation period

- Symptoms of the disease

- Fatality of the disease

- Transmission potential of asymptomatic/presymptomatic patients

Since effective health policies can only be developed on the basis of such information, governments have an imperative to support research by direct investment and collaborating with private research facilities or pharmaceutical companies.

Development of Testing Methods

In the early stages of disease spread, it is crucial to develop testing methods to detect the virus. There are two major types of diagnostic tests available for Covid-19: rapid antigen tests and molecular tests. Rapid antigen tests are used to identify patients who are symptomatic or asymptomatic, and results are available within 15 to 30 minutes (Williams, 2021). Conducted with a nasal swab, rapid antigen tests detect the protein coat surrounding the viral RNA genome using antibodies that bind to the antigen virus (Fred Hutch, 2021). While rapid antigen tests are quick and simple, they may be inaccurate; a patient who does not have much of the virus in their nose or throat in the early stages of infection may test negative; in a recent study of more than 700 athletes, the tests caught 78% of symptomatic cases, while it only caught 39% of asymptomatic cases (Bendix, 2022).

Molecular tests, on the other hand, detect SARS-CoV2 genetic material by utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology. A fluid sample is analyzed, and amplification via PCR allows the test to detect even small amounts of SARS-CoV2 in the sample (European Observatory on Health & Policies, 2020). While molecular tests can take time and may have to be done in a separate lab, they are more accurate. In order to use such technologies to develop specific testing methods for a new virus it would be important to investigate the components of the virus, such as the protein coat, genetic material and specific antibodies that can bind to them. Developing accurate test methods is the basis for many other policies such as contact tracing or quarantine measures. And it is especialy critical if the virus is identified to cause asymptomatic cases and spread in the presymptomatic stages.

Although rapid antigen self-tests are not the most accurate, suspected patients should be instructed to use rapid antigen self-test kits in the initial stages, and receive molecular tests as soon as possible from testing facilities, as they are less expensive, provide results faster, and are easier to distribute. Testing kit supply should be secured by subsidizing or collaborating with companies with adequate production facilities to lower production costs and increase quantity supplied, making sure kits can be distributed widely among the population.

Maskwearing Policy

Mask wearing is an effective way to prevent transmission for the next COVID pandemic. A combination of policies to improve public awareness about mask wearing and incentivize citizens to voluntarily wear masks in public settings should be used.

Governments responded in different ways in order to prevent the spread of Covid-19. One important aspect of pandemic prevention is mask wearing. In the case of Covid-19, mask-wearing has proven to be effective in preventing transmission from person to person. The SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads primarily through exhalation when infected people breathe, talk, cough, or sneeze in droplets that are smaller than 10µm in diameter. While larger droplets fall out of the air rapidly due to their weight, smaller droplets and dried particles have the potential to remain suspended in the air for some time, leading to mass infections in indoor places with poor ventilation (Jayaweera et al., 2020).

The two primary protective effects of mask wearing are first, preventing aerosol cloud formation from an infected person and blocking turbulent jets generated by coughing. Second, masks can filter aerosols or droplets transmitted by infected individuals, although the efficacy depends on the type of mask (Li et al., 2020). In terms of source control, masks can block the carrying of virus-containing droplets into the air. Source control is important because it can prevent infected persons from spreading the virus to other people.

Due to the potential for asymptomatic transmission, it is difficult to distinguish infected individuals from others. At least 50% or more of all transmissions are from individuals who never develop symptoms or are in the presymptomatic stage; notably, the viral loads of these individuals are not significantly different compared to those of symptomatic patients (Payne et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020). Considering the transmission potential of asymptomatic patients, it is crucial to establish the importance of masks as a primary means of preventing the spread of the virus.

Many different types of masks exist, including N95 masks, which are medical masks that meet US CDC standards, surgical masks, and homemade cloth masks which, although less protective, still reduce transmission (World Health Organization, 2020b). Researchers suggest that the best protection comes from certified quarantine masks. Although there is reduced protection when wearing cloth masks compared to medical masks, cough pressure can be significantly reduced by wearing any type of mask (Inouye et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2014).

The efficacy of mask wearing, similarly to the concept of herd immunity in vaccination, increases with the number of people wearing masks. Findings from serial cross-sectional studies identified that a high percentage of self-reported mask wearing is associated with higher probability of transmission control in the US across all levels of physical distancing (Rader et al., 2021). An analysis by the CDC of schools in Arizona revealed that the odds of a school-associated Covid-19 outbreak were 3.7 times higher in schools with no mask requirement compared with schools with early mask requirements (Jehn et al., 2021). There are several examples of how mask-wearing likely helped prevent mass infection. In May 2020, two stylists at a Missouri hair salon with coronavirus saw 140 clients. The salon they worked in required both stylists and clients to wear masks, consistently with local government guidance. Both stylists and 98% of clients wore face coverings, and no new cases linked to the salon were identified (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Karimi, 2020). During an outbreak in March 2020 in the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, carrying 4800 sailors where approximately 25% of the people onboard were infected by Covid-19, persons who wore masks experienced a 70% lower risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV2 infection (Payne et al., 2020).

A wide range of factors impact whether people wear masks or not, including culture, pandemic severity, and government public health policies or recommendations. It is important to persuade the general public that mask wearing is effective and important. Mask denial has been a big issue in the US, and one of the factors include the culture of individualism in America; a survey in June 2020 found that 40% of Americans who do not wear a mask do so as it is their “right as an American citizen not to wear a mask” and 24% responded that “it is uncomfortable.” 18% answered it is because “they do not have access to a mask,” and 67% of respondents who were men of color – responded that it is because “they do not want to be mistaken as a criminal” (Sanchez, 2020). In addition, at the early stage of the pandemic, public health officials in many countries in North America and Europe discouraged healthy people from wearing masks (Forbes, 2020).

In contrast with the US, in East Asia most countries were able to successfully utilize masks as an effective tool to slow COVID-19 spread via voluntary mask wearing, and mask mandate policies were enacted with less controversy, in part owing to different attitudes towards government. Wearing a mask in these countries has long been acceptable for other reasons, such as avoiding pollution and exposure to other respiratory viruses (i.e., SARS, MERS, etc).

It is therefore important to create a culture where mask wearing is socially acceptable even in non-pandemic situations so that culture does not hinder population-wide mask wearing during future pandemics. Public health officials should emphasize that mask-wearing is not necessarily associated with serious sickness or criminal action by using public campaigns and advertisements. The government should also secure supply of masks especially in the early stages of a virus outbreak to make sure every citizen can have access to one, and problems such as hoarding do not occur. In order to make this possible, the government should be aware of which companies have the capacity of mass-producing masks in a short period of time so it can provide subsidies for mask production when needed.

Based on the aforementioned June 2020 survey on mask wearing, 60% of Americans who wear a mask do so “to protect themselves and others.” Therefore, in order to get as many people to wear masks especially in transmission-likely public or crowded settings it is important to stimulate community-oriented spirit and promote the effect of mask wearing as a means of protecting self and others using public advertisements and campaigns. Enforcement of mask wearing in severe situations can be possible only when a large proportion of the population agrees with it, and that is only possible if not wearing a mask is perceived as morally unacceptable.

Contact Tracing

Contact tracing is a procedure that identifies all people who were in close contact with a suspected or positive case of Covid-19. Effective contact tracing in the early stages of an epidemic when there are low case numbers can help stop the spread of the disease completely by tracing and isolating all infected individuals and providing intensive care. One study in Hong Kong found that 19% of the cases of Covid-19 were responsible for 80% of transmissions, and 69% did not transmit the virus to anyone (Lewis, 2020). The WHO benchmark for successful Covid-19 contact tracing is to trace and quarantine 80% of close contacts within 3 days of a case being confirmed so that it does not spread further (Lewis, 2020). Case investigation, diagnosis, and identification of any symptomatic and asymptomatic contacts that got infected by the case, therefore, is crucial for contact tracing to be used as an effective tool to decrease or slow the spread of a pandemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022a). Contact tracing mainly involves the test-trace-isolate sequence, where suspected cases are tested, and if positive, contacts are traced and isolated/quarantined if needed (Lewis, 2020).

In order for the test-trace-isolate sequence to keep up with mounting cases, short, compact, and effective training programs for tracers should be developed so that public health officials, doctors, physicians, nurses etc. can act right away as tracers, and the tracers can keep up with all new cases. The government also has to make sure that contact tracing is an operation that is well-paid and well-treated. Many wealthy nations during the Covid-19 pandemic struggled to hire enough contact tracers that are qualified, and tracers generally tend to work long hours and be low-paid (Khazan, 2020). Once a reliable health workforce is secured, tracers can get ahead of rapidly spreading outbreaks by tracing and quarantining second-order contacts. This was the approach taken in Vietnam during the Covid-19 pandemic. Japan followed another successful approach, backwards contact tracing, where a new case’s contacts were traced as far as a day before they were infected to identify who likely infected them (Williams, 2021).

Countries have had different contact tracing policies that are centralized or decentralized. Centralized contact tracing is done at the national level, coordinated by a Ministry of Health or a subordinate agency. Decentralized contact tracing can be accomplished by sharing the responsibility with regional governments and districts. For instance, in Spain, contact tracers at a regional level tracked people who were in close contact with a case within two days before the onset of symptoms or a positive test result. In England, NHS Test and Trace, a government-funded service developed in 2020 to slow the spread of Covid-19, operated as a partnership between national and local officials. The United States also has differing contact tracing policies and methods depending on the state. Some countries require general practitioners and physicians to record their patients’ close contacts (European Observatory on Health & Policies, 2020). While there should be a centralized contact tracing system to keep track of case numbers and movements between regions, tracing of specific cases should be assigned to regional districts for increased efficiency and use of the local workforce.

Data surveillance technologies and smartphone apps can also be used to speed up contact tracing. In the case of Covid-19, contact tracing apps for smartphones, which record location data and notify users if they were in proximity to a patient and need to get tested, have been developed by at least 46 countries to avoid repeated calling by tracers and increase efficiency. Many apps use the Google/Apple Exposure Notification (GAEN) system, which uses bluetooth signals to detect when two users are close together. For instance, the NHS Covid-19 app, first released in September 2020, traces contacts and notifies users if they have to self-isolate. Data suggests that the app might have helped prevent more than 224,000 infections between October and December 2020, and every 1% increase in app users was predicted to reduce the number of infections by up to 2.3% (Lewis, 2021).

Such applications for contact tracing can be downloaded and used by citizens in emergency situations, and when case numbers decrease, people can delete the app for privacy reasons. The use of technology can allow convenient second-order contact tracing and backward tracing, especially if the user has been to public settings in crowded areas. Due to data privacy concerns, however, it would be impossible to persuade everyone to download the app to record their location information. Strong incentives need to be given for voluntary downloading; in Singapore, only about 17% of the population downloaded Singapore’s contact tracing app TraceTogether voluntarily (Chong, 2020). Requiring citizens to download an app or recording unique QR codes for each building they go into to record location information in public buildings, transportation or crowded indoor areas can be one solution.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, tracing apps often conflicted with data privacy issues; for instance, an app launched in Norway on April 16th 2020 was discontinued in June 15th, and all data collected were deleted due to privacy issues regarding location history raised by individual users and the Norwegian Data Protection Agency (European Observatory on Health & Policies, 2020). Furthermore, people in quarantine also experience economic hardships and shortages in basic needs such as food, medicine, water, and communication (Botes & Thaldar, 2020). Therefore, in order to enforce quarantine effectively, the government has to ensure sufficient access to resources to satisfy the basic needs of people whose movement is restricted, especially individuals who live alone or are in vulnerable socio-economic groups. Lack of support for people who fall ill or need to quarantine is one factor that contributes to trust deficit and disobedience; therefore, for each case of quarantine, there needs to be adequate financial compensation for the personal and economic hardships that the individual experiences as a result of quarantine (Lewis, 2021). In order for this to happen, the government needs to invest in accurately identifying each case and providing basic necessities and goods for the individual to be able to survive without leaving their quarantine area.

Full lockdowns and workplace closures should only be used as a last resort to reduce case numbers because they can have detrimental impacts on household income, mental health, and international trade. (Aragona et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2021; Mukunoki, 2021). But even on the individual level, quarantine is difficult to enforce due to problems of noncompliance or lack of government trust. In the test-trace-isolate sequence, problems can occur in every step. People could get infected and not know it or delay getting tested. People who test positive or were in close contact with a positive case may not isolate when requested; 75% of people who reported someone in their household had symptoms said that they had left their house in the past day, according to a survey held in May in the UK (Smith et al., 2020). Tracers failed to get in touch with one in eight people who tested positive for Covid-19 in England, and 18% of those who are reached provide no details for close contacts. In some regions of the US, it was found that more than half of the people who tested positive provided no details of contacts when asked (Lewis, 2020). A survey conducted by Pew Research Center found that only 48% of US adults said they are comfortable with all three steps of speaking with a public health official, sharing information about contacts, and quarantining if needed. And even for this 48% of people, there may be a disparity between willingness and real action (Rainie, 2020).

Vaccination

Substances such as bacteria or viruses that can cause disease in the human body are detected and fought by different cells of the immune system (World Health Organization, 2020a). The immune system can be divided into innate immunity and adaptive immunity; innate immunity helps the body resist diseases caused by new pathogens, while adaptive immunity can respond to specific pathogens previously encountered when they enter the body again (InformedHealth, 2020). Vaccines boost the adaptive immune reponse by pre-emptively exposing the body to a weakend form of a pathogen so that it may develope specific antibodies to that pathogen before being infected. Vaccines can be developed with a weakened form of the whole pathogen, or use parts of that pathogen (for example, the COVID-19 spike protein) (World Health Organization, 2021).

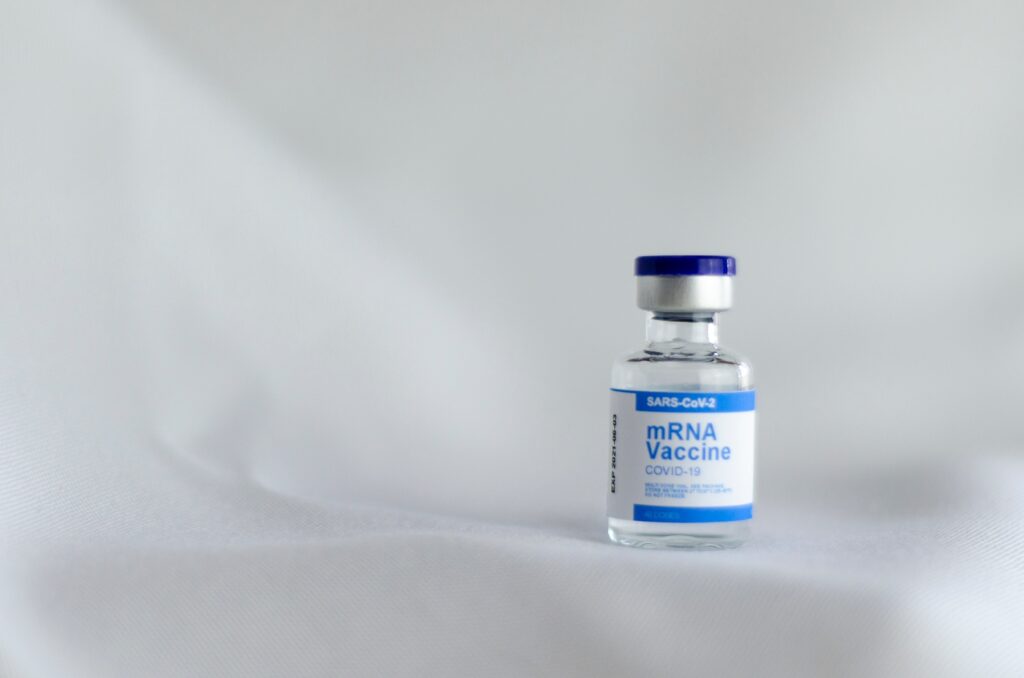

Fig 1. Image of an mRNA Vaccine (Source: Unsplash, Spencer Davis)

As of October 2022, four Covid-19 vaccines had been authorized or approved for use in the United States: Pfizer-BioTech (FDA-approved in August 2021), Moderna (authorized for emergency use in December 2020), Johnson & Johnson’s (authorized for emergency use in February 2021), and Novavax (authorized for emergency use in July 2022). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022; U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2021, 2022). The vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioTech and Moderna are mRNA vaccines, meaning that they use the genetic material of SARS-CoV2 to trigger immune responses. When the mRNA vaccine is injected in the upper arm, the mRNA contained in the vaccine enters the muscle cells and triggers them to produce spike proteins, identical to that of SARS-CoV2. The spike proteins expressed on the surface of the muscle cells are recognized as foreign by the immune system and stimulate the development of an adaptive immune response to detect and fight Covid-19 infection upon future exposure (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022d). Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine is a viral vector vaccine – a modified version of a different species of virus identical to SARS-CoV2. The viral vector enters the muscle cells and triggers them to produce spike proteins, triggering immune responses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022e). Due to a heigtened risk of serious adverse events, such as Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (TTS), Guillain-Barre Syndrome, or Myocarditis with the viral vector vaccine, the CDC prefers the mRNA vaccines over the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in most cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022b).

While aiming to secure vaccine supply, vaccination should be prioritized for those working in the healthcare sector, especially in the first lines of pandemic prevention. In terms of age group, older age groups who are more vulnerable to severe symptoms of coronavirus disease should be prioritized. Side effects should be monitored carefully as some vaccines may trigger autoimmune side effects (Mahroum & Shoenfeld, 2022). In order to encourage vaccination and halt the dissemination of misinformation about vaccines, cases of vaccination side effects should be accurately diagnosed, identified, and carefully treated by medical professionals. These measures will help increase the trust of the general public in government-approved and provided vaccines. Additional policies, such as a requiring a “vaccine pass,” a document that contains vaccination details or test results when traveling abroad or in crowded public spaces, is also recommended when a positive public opinion about the vaccine is formed. The government should use caution, however, in allowing for the exemption exceptional groups of people that cannot be vaccinated due to health or religious reasons (National Health Service, n.d.).

Conclusion

The next pandemic of similar or larger scale than Covid-19 may come earlier than expected, and if the world is as unprepared as it was for Covid-19, great socio-economic harm will be inevitable. In order to minimize harm and prepare for the next pandemic, the following measures are recommended in the preparation stage:

- Repair healthcare systems and develop a system to reach out to marginalized groups in society

- Invest in public hygiene and sanitation

- Achieve flexibility in organizations and institutions; training to use online platforms and smooth switching between online and offline workplaces/schools

- Support telecommunication technology for access to distance learning and work

- Utilize public advertisements and campaigns to form a culture where mask-wearing is socially acceptable

- Develop technology that can be used nation-wide for contact tracing; Make this technology privacy and user-friendly so that populations that are digital-illiterate can use easily

Taking these specific steps in order to prepare the society for the next viral outbreak can help mitigate the devastating effects to society that Covid-19 has clearly demonstrated a pandemic can bring. The world post-Covid-19 is not a post-pandemic world, but a pre-pandemic world. These guidelines shuold be integrated into the new-normal society to equip it for the next pandemic.

References

Aragona, M., Barbato, A., Cavani, A., Costanzo, G., & Mirisola, C. (2020). Negative impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health service access and follow-up adherence for immigrants and individuals in socio-economic difficulties. Public Health, 186, 52-56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.055

BANK, T. W. (2020). COVID-19 to Plunge Global Economy into Worst Recession since World War II. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-into-worst-recession-since-world-war-ii

Bendix, Aria. “Rapid Covid Tests Give Many False Negatives, but That Might Mean You’re Not Contagious.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 15 June 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/rapid-covid-tests-false-negatives-rcna33502.

Botes, W. M., & Thaldar, D. W. (2020). COVID-19 and quarantine orders: A practical approach. S Afr Med J, 110(6), 469-472. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2020v110i6.14794

Brooks, J. T., & Butler, J. C. (2021). Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA, 325(10), 998-999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1505

CENTER FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT. What’s Next? Predicting The Frequency and Scale of Future Pandemics. https://www.cgdev.org/event/whats-next-predicting-frequency-and-scale-future-pandemics

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC calls on Americans to wear masks to prevent COVID-19 spread. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0714-americans-to-wear-masks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a). Interim Guidance on Developing a COVID-19 Case Investigation & Contact Tracing Plan: Overview. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/contact-tracing-plan/overview.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022b). Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine: Overview and Safety. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/janssen.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022c). Stay Up to Date with Your COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022d). Understanding mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/mrna.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022e). Understanding Viral Vector COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/viralvector.html

Chong, C. (2020). About 1 million people have downloaded TraceTogether app, but more need to do so for it to be effective: Lawrence Wong. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/about-one-million-people-have-downloaded-the-tracetogether-app-but-more-need-to-do-so-for

Ciotti, M., Ciccozzi, M., Terrinoni, A., Jiang, W.-C., Wang, C.-B., & Bernardini, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 57(6), 365-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198

DELÉCHAT, CORINNE, and LEANDRO MEDINA. “What Is the Informal Economy?” IMF, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/12/what-is-the-informal-economy-basics.

Edelberg, M. B. L. B. W. (2021). 11 facts on the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.brookings.edu/research/11-facts-on-the-economic-recovery-from-the-covid-19-pandemic/

European Observatory on Health, S., & Policies. (2020). Effective contact tracing and the role of apps: lessons from Europe. Eurohealth, 26(2), 40-44. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336294

European Union EXTERNAL ACTION. (2021). EU statement on the WHO-led COVID-19 origins study. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-statement-who-led-covid-19-origins-study_en

Forbes. (2020). Should Everyone Wear A Mask In Public? Maybe—But It’s Complicated. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tarahaelle/2020/04/01/should-everyone-wear-a-mask-in-public-maybe-but-its-complicated/?sh=540f6a5a02fd

Fred Hutch, S. C. C. A., and UW Medicine Complete Restructure of Partnership,. (2021). How Scientists Test for COVID-19. https://www.fredhutch.org/en/research/diseases/coronavirus/serology-testing.html

Garfield, N. P. R. K. C. C. R. (2021). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

Gene, F., Paul, D. R., Isaac, A. N., & Emma, C. N. (2021). Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46554.pdf

Gupta, A., Zhu, H., Doan, M. K., Michuda, A., & Majumder, B. (2021). Economic Impacts of the COVID−19 Lockdown in a Remittance-Dependent Region [https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12178]. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(2), 466-485. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12178

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr Med Res Pract, 10(2), 78-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T., & Frey, A. (2021). Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement-A Systematic Review [Systematic Review]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289

Henry, F. A., N. (2020). Will the Coronavirus End Globalization as We Know It? The Pandemic Is Exposing Market Vulnerabilities No One Knew Existed. Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues. https://uschinadialogue.georgetown.edu/publications/will-the-coronavirus-end-globalization-as-we-know-it-the-pandemic-is-exposing-market-vulnerabilities-no-one-knew-existed

InformedHealth. (2020). The innate and adaptive immune systems. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279396/

Inouye, S., Okabe, N., Obara, H., & Sugihara, Y. (2010). Measurement of Cough-Wind Pressure: Masks for Mitigating an Influenza Pandemic. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 63(3), 197-198. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.63.197

International Labour organization. (2020). ILO: As job losses escalate, nearly half of global workforce at risk of losing livelihoods. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_743036/lang–en/index.htmn

Jayaweera, Mahesh, et al. “Transmission of COVID-19 Virus by Droplets and Aerosols: A Critical Review on the Unresolved Dichotomy.” Environmental Research, Elsevier Inc., Sept. 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7293495/.

Jehn, M., McCullough, J. M., Dale, A. P., Gue, M., Eller, B., Cullen, T., & Scott, S. E. (2021). Association Between K–12 School Mask Policies and School-Associated COVID-19 Outbreaks — Maricopa and Pima Counties, Arizona, July–August 2021 [Journal Article]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 70(39):1372-1373, 70(39). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/110732

Jung, H., Kim, J. K., Lee, S., Lee, J., Kim, J., Tsai, P., & Yoon, C. (2014). Comparison of Filtration Efficiency and Pressure Drop in Anti-Yellow Sand Masks, Quarantine Masks, Medical Masks, General Masks, and Handkerchiefs. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 14(3), 991-1002. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2013.06.0201

Karimi, F. (2020). Two hairstylists who had coronavirus saw 140 clients. No new infections have been linked to the salon, officials say. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/11/us/missouri-hairstylists-coronavirus-clients-trnd/index.html

Khazan, O. (2020). The Most American COVID-19 Failure Yet. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/08/contact-tracing-hr-6666-working-us/615637/

Klein, S. L., & Flanagan, K. L. (2016). Sex differences in immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(10), 626-638. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.90

Lewis, D. (2020). Why many countries failed at COVID contact-tracing — but some got it right. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03518-4

Lewis, D. (2021). Contact-tracing apps help reduce COVID infections, data suggest. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00451-y

Li, T., Liu, Y., Li, M., Qian, X., & Dai, S. Y. (2020). Mask or no mask for COVID-19: A public health and market study. PLoS One, 15(8), e0237691. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237691

Mahroum, N., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination can occasionally trigger autoimmune phenomena, probably via inducing age-associated B cells [https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.14259]. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 25(1), 5-6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.14259

McKinsey & Company. (2020). How COVID-19 has pushed companies over the technology tipping point—and transformed business forever. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever

Morse, S. S., Mazet, J. A. K., Woolhouse, M., Parrish, C. R., Carroll, D., Karesh, W. B., Zambrana-Torrelio, C., Lipkin, W. I., & Daszszak, P. (2012). Prediction and prevention of the next pandemic zoonosis. The Lancet, 380(9857), 1956-1965. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673612616845

Mukunoki, K. H. H. (2021). Impacts of Lockdown Policies on International Trade. Asian Economic Papers, 20(2), 123-141. https://direct.mit.edu/asep/article-abstract/20/2/123/97313/Impacts-of-Lockdown-Policies-on-International

National Health Service. NHS COVID Pass. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/nhs-covid-pass/

Payne, D. C., Smith-Jeffcoat, S. E., Nowak, G., Chukwuma, U., Geibe, J. R., Hawkins, R. J., Johnson, J. A., Thornburg, N. J., Schiffer, J., Weiner, Z., Bankamp, B., Bowen, M. D., MacNeil, A., Patel, M. R., Deussing, E., & Gillingham, B. L. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Serologic Responses from a Sample of U.S. Navy Service Members – USS Theodore Roosevelt, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69(23), 714-721. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e4

POLITICO. (2020). Trudeau warns U.S. against denying exports of medical supplies to Canada. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/03/3m-warns-of-white-house-order-to-stop-exporting-masks-to-canada-163060

Rader, B., White, L. F., Burns, M. R., Chen, J., Brilliant, J., Cohen, J., Shaman, J., Brilliant, L., Kraemer, M. U. G., Hawkins, J. B., Scarpino, S. V., Astley, C. M., & Brownstein, J. S. (2021). Mask-wearing and control of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the USA: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Digital Health, 3(3), e148-e157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30293-4

RAINIE, C. M. L. (2020). The Challenges of Contact Tracing as U.S. Battles COVID-19. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/10/30/the-challenges-of-contact-tracing-as-u-s-battles-covid-19/

Roberts, D. L., Rossman, J. S., & Jarić, I. (2021). Dating first cases of COVID-19. PLOS Pathogens, 17(6), e1009620. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009620

Sanchez, E. D. V. G. R. (2020). American individualism is an obstacle to wider mask wearing in the US. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/08/31/american-individualism-is-an-obstacle-to-wider-mask-wearing-in-the-us/

Sills, J., Bloom, J. D., Chan, Y. A., Baric, R. S., Bjorkman, P. J., Cobey, S., Deverman, B. E., Fisman, D. N., Gupta, R., Iwasaki, A., Lipsitch, M., Medzhitov, R., Neher, R. A., Nielsen, R., Patterson, N., Stearns, T., van Nimwegen, E., Worobey, M., & Relman, D. A. (2021). Investigate the origins of COVID-19. Science, 372(6543), 694-694. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj0016

Smith, L. E., Amlȏt, R., Lambert, H., Oliver, I., Robin, C., Yardley, L., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). Factors associated with adherence to self-isolation and lockdown measures in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. Public Health, 187, 41-52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.07.024

Sriam, A. (2021). Zoom shares tumble as revenue growth slows. https://www.reuters.com/technology/zoom-shares-tumble-revenue-growth-slows-2021-11-23/

Tazeen, F. H., A. P. Najeeb, S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on labor market outcomes: Lessons from past economic crises. https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/impact-covid-19-labor-market-outcomes-lessons-past-economic-crises

U.S. FOOD & DRUG ADMINISTRATION. (2021). FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

U.S. FOOD & DRUG ADMINISTRATION. (2022). Spikevax and Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/spikevax-and-moderna-covid-19-vaccine

UCDAVIS HEALTH. (2020). Different types of COVID-19 tests explained. https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/different-types-of-covid-19-tests-explained/2020/11

Williams, N. (2021). Types of COVID-19 Test. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Types-of-COVID-19-Test.aspx

Wolf, Martin. “The Winding Road to Global Recovery Is through a Thicket of Risks.” Subscribe to Read | Financial Times, Financial Times, 25 Jan. 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/f681bdeb-f93a-4ec4-8356-77caf70f1c28.

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2020a). How do vaccines work? https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/how-do-vaccines-work

World Health Organization. (2020b). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

World Health Organization. (2021). The different types of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-race-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-explained

World Health Organization. (2022). WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

Zou, L., Ruan, F., Huang, M., Liang, L., Huang, H., Hong, Z., Yu, J., Kang, M., Song, Y., Xia, J., Guo, Q., Song, T., He, J., Yen, H.-L., Peiris, M., & Wu, J. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(12), 1177-1179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2001737

Related Posts

The Gut May Be The Door to Effective Depression Treatment

First Author: Jillian Troth1 Co-Authors [Alphabetical Order]: Roxanna Attar2, Caroline...

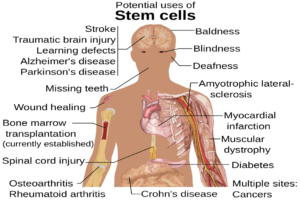

Read MoreCranial Cartography: A New Method for Visualizing Blood Vessels and Stem Cells in the Skull

The diagram above displays the many potential uses of stem...

Read MoreCOVID-19 Pneumonia – A Different Illness Than Its Traditional Counterpart

Figure 1: This is an image of a child with...

Read MoreUsing Metabolic Network Models to Identify New Antibiotic Targets

Source: Nastya Dulhiier How do you treat bacterial infections without...

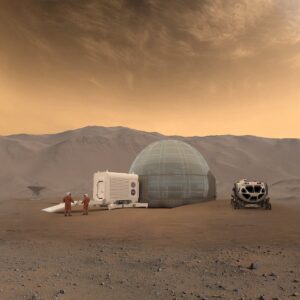

Read MoreHow Many Humans Does it Take to Host a Planet?

Figure 1: This is an artist’s rendering of a potential...

Read MoreThe Critical Role of Sleep in Determining Reaction to Daily Life

Source: Pixabay Sleep plays an extremely important role in physical...

Read MoreJY