Figure 1: People group crowd

Source: Pixabay

Prejudice refers to an unfavourable attitude towards an individual or a group, and has been a prevalent danger across time and culture (Dovidio et al., 2017). In such a diverse world, people are identified as belonging to different groups based on their features such as race or ethnicity, gender, and age. The prejudices between different groups elicit intergroup hostility and conflicts, so it is important to explore strategies that reduce prejudices. Peaceful intergroup contact has long been recognized as the most important contribution to prejudice reduction (Dovidio et al., 2011). Early research studied direct contact can improve relations, and near the end of the 20th century, psychologists found that indirect contact can as well (Dovidio et al., 2017). Direct contact refers to physical contact with others while indirect contact comes in 3 forms: (1) extended contact: mere knowledge of positive cross-group friendship; (2) vicarious contact: observing that an ingroup member interacts with a member from a different group; and (3) imagined contact: imagining positive cross-group interactions. In addition to direct and indirect contact, another strategy that has been effective at decreasing prejudice is social categorization, which reduces bias by changing people’s perception of their group identity (Nier et al., 2001). In this essay, I will critically evaluate and compare these three bias-reduction strategies: direct contact, indirect contact, and social categorization.

Introduction to Direct Intergroup Contact

Direct intergroup contact might exacerbate prejudice under a few circumstances, but properly constructed contact is quite effective in prejudice reduction. This is supported by the results of the Robbers cave experiment (Sherif et al., 1954; Sherif et al., 1961).

Figure 2: Robbers cave state park

Source: Flickr

The experiment worked as follows. In order to investigate intergroup relations, the experimenters designed a field study. They organized a camp and invited middle-class, young American teenagers. The experiment consisted of three stages. In Stage 1, participants were divided into two groups and geographically isolated each other. In Stage 2, the two groups were involved in intergroup contact through competitive activities. In Stage 3, they had to cooperate with the other group to achieve a goal. The experimenters observed the behaviour of all the boys throughout this process, trying to investigate which sort of contact is effective in prejudice reduction. The results showed that contact in the competitive settings (Stage 2) increased prejudice, conflicts, and hostility. Moreover, normal contacts in this stage such as eating food in the same room became the opportunity to display overt acts of hostility. In contrast, when the two groups had to achieve a superordinate goal, behaviours of intergroup cooperation increased while intergroup friction decreased. Thus, contact could yield opposite results in different situations.

At the time, Allport (1954) suggested four conditions for contact to reduce prejudice: equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation, and support of authorities. Under these circumstances, contact intervention could significantly reduce intergroup tension. This hypothesis has received extensive empirical support from both laboratory and field research (Pettigrew, 1998). One meta-analysis collected 713 independent samples from 515 studies to investigate the effects of contact intervention in different contexts (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). the researchers discovered that contact intervention could generally reduce intergroup prejudice, but the effects were more significant under Allport’s optimal conditions. However, this study was criticized by Hewstone et al. (2014) as the majority of studies in the database were cross-sectional studies, which measured contact and prejudice at the same time. This limits the ability to conclude causal effects between contact and prejudice because in this case, no adequate time was given for causal effects to act on.

Hewthorne highlighted instead the results of his prior longitudinal study, which measured variables within a period of time (Hewstone et al., 2008). There is a long history of antagonism between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland. Hewstone and fellow researchers measured levels of contact and bias by conducting surveys of Catholics and Protestants. Data were collected at Time 1 and Time 2, one year apart. With contact in the previous year, they observed reduction of bias at Time 2. Bias at Time 1 had no significant effects on the frequency of contact afterward. This suggests a causal effect from contact to reduced prejudice, since bias does not really affect contact. Based on the above papers, we can see that the effect of direct contact is condition-specific, but overall, a nice strategy to adopt especially in favourable conditions.

Figure 3: Catholic area riots after Protestant marches in Northern Ireland

Source: Maxism

How Direct Intergroup Contact Works

Direct contact improves relations through both cognitive and affective processes (Dovidio et al., 2011). Cognitively, direct contact increases learning of members from the other group and affects how people socially categorize themselves (Pettigrew, 2008; Miller, 2002). Increased learning can uncover similarities, enhance liking, and reduce ambiguity about intergroup interactions (Dovidio et al., 2017). However, the mediation effect of increased knowledge was not strong (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Direct contact reduces bias by affecting social categorization in two ways: de-categorization and re-categorization. Through direct and personal contact, people’s group identity become less salient (Miller, 2002). People decategorize their group identity in this individual-to-individual interaction. Alternatively, through positive contact in cooperation activities, people recategorize group identities from different groups to the same group (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2009). In other words, they changed their perception of the other group from ‘they’ to ‘we’.

Figure 4: Re-categorisation of group identity. A new member joined the group, and the group boundaries are modified

Source: static the noun project

Effectively, contact reduces bias by reducing feelings of anxiety and increasing empathy (Pettigrew, 2008). Anxiety comes from the anticipation of negative experiences in intergroup contact (Stephan & Stephan, 1985). One recent empirical study investigated its mediating role through cooperative video game play (Stiff & Kedra, 2020). Playing with members from the other group reduced anxiety levels and decreased intergroup bias accordingly.

Figure 5: Representation of intergroup anxiety faced by outgroup members

Source: Pixabay

Enhanced empathy was also found to mediate the contact effect on prejudice. Johnston and Glasford (2018) studied intergroup relations between Black/African Americans and White Americans. The more high-quality contact, the more empathy was shown, which facilitated outgroup helping. Together, this study and the others mentioned answer the question of how direct contact improves intergroup relations.

Limitations of Direct Intergroup Contact

Whereas direct contact has proven benefits, it is limited in its practical implementation. Only when there is a chance for contact can direct contact strategy act on intergroup relations and diminish prejudice (Turner, Hewstone, & Voci, 2007). However, in reality, some groups are segregated and have no opportunity for interaction. For example, North and South Koreans continuously stand on the brink of war although they have the same ethnicity and language. The two groups are separated by a strictly maintained border and the authorities prevent inter-country interactions. This leads to limited opportunity for contact, causing obstacles for direct contact implementation.

Figure 6: Map of North and South Korea

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Introduction to Indirect Contact

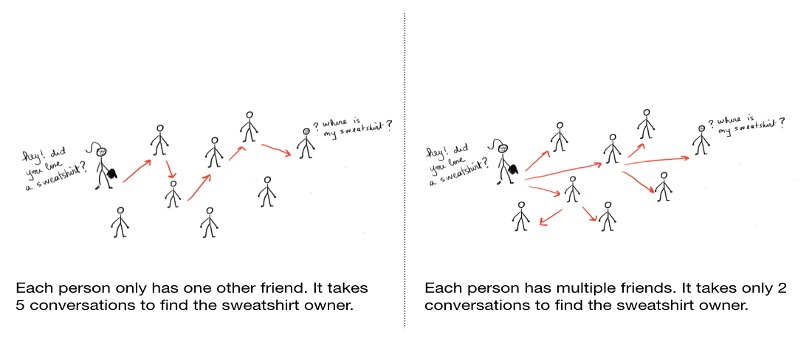

To look beyond the limitations of direct contact, researchers have expanded their study of contact to indirect forms, which result in many unique benefits. Compared with direct contact, indirect contact has a relatively lower demand for contact opportunities. Extended and vicarious contact only needs a few cases of cross-group interactions, while personal contact has to be frequent and widespread. Imagined contact merely involves a mental simulation of intergroup contact. Therefore, indirect forms can be applied to disconnecting intergroup contexts. The benefit of indirect contact is that it can positively predict future direct contact, with evidence from longitudinal studies indicating that indirect contact could curtail intergroup anxiety (Wölfer et al., 2019). This means indirect contact can be prioritized in some extremely intense relations, to prepare for future direct contact. Another advantage is that, while personal contact changes an attitude of a single member at a time, indirect contact can have a wider reaching impact (Dovidio et al., 2017). This is because the knowledge of cross-group contact can spread quickly, and over a wide range. Each member who knows this information can be affected. Dovidio (2017) described this influence as “cascading and almost viral.”

Figure 7: Extended contact’s ‘viral’ influence within a group of individuals

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although more people are affected by indirect contact, its strength of prejudice-reduction might be weaker than direct contact. This assertion is supported by Pettigrew et al. (2007), who showed that both direct and indirect contact could significantly reduce threats between groups, but that indirect contact only has a subtle effect on interpersonal prejudice. Generally, despite its weaker strength, indirect contact is valuable when groups are segregated, or are more antagonistic to each other before intervention.

Introduction to Social Categorization

Social categorization is another intervention to reconcile intergroup hostility, and it reduces conflicts by modifying group boundaries (Hall et al., 2009). People naturally feel and act positively to their group members while displaying negative attitudes and actions towards outgroup members (Hewstone et al., 2002). This happens even when their group identity is defined by meaningless criteria such as a coin flip (Locksley et al., 1980).

Social categorization involves decategorizing and recategorizing the identities of group members, establishing new group relations (Nier et al., 2001). Houlette et al. (2004) tested this intervention with the green circle program. 830 children from first and second grade were randomly assigned to three groups, including a regular program, an enhanced program, and a control condition. Under the regular green circle condition, children had 12-hour sessions in total with their instructors. Children were guided to include people within a green circle, building their ‘green circle communities’. Some classmates might be excluded by how they looked or where they came from. Instructors led children to think about people out of the circle, and gradually enlarge the circle to include more people. The green circle was akin to a group boundary, and the process of enlarging the circle was the process of restructuring social categorization. In the enhanced program, the perimeter of classrooms was surrounded by a large circle made of green plastic tape, and all students wore the same green vests. This further emphasized their common identity in the classroom. Results showed that children participating in these programs were more willing to play with others different from themselves.

Figure 8: The Green circle paradigm, implemented in a kindergarten

Source: Flickr

Ultimately, the researchers found that there was no significant difference between enhanced and regular conditions. Paluck & Green (2009) commented that laboratory interventions like the green vests had only slight effects in real-world settings. Later studies, however, seldom take social categorization as a ‘pure’ intervention for bias-reduction (Prati, Crisp & Rubini, 2020). So, social categorization is used to reduce inter-group bias only in conjunction with direct or indirect contact, but not alone, because it is not powerful enough.

Applications of Social Categorization

Although it lacks support from field experiments, social categorization offers explanations for intergroup contact. As mentioned above, it is one of the most important mediators for direct contact and bias-reduction (Dovidio et al., 2011). To some extent, we could say that social categorization has been applied in optimal conditions in Allport’s contact hypothesis. Equal status makes a platform for inclusion. It could be hard to incorporate others as a common group identity if they have unequal status. Besides, common goals and intergroup cooperation are conditions where people easily build the perception of ‘the whole group’ (Gaertner et al., 2016). As well as direct contact, it also relates to extended contact. Learning of cross-group friendship can increase inclusion of others in the self because people would be led to think that ‘my friend’s friend is my friend’ (Wright et al., 1997). In this case, members recategorize intergroup relations by including outgroup members in the self-group. Generally, social categorization is the underlying mechanism behind why contact works for reducing bias.

Summary

To conclude, research has demonstrated multiple pieces of evidence for the effect of contact intervention on bias-reduction. Direct contact can fairly reconcile intergroup relations, especially under certain optimal conditions: equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation, and support of authorities. Not only does research study when and where it works, but it also investigates how and why contact reduces prejudice. The mechanisms include cognitive components (increased knowledge and social categorization) and affective components (reduced anxiety and improved empathy). However, direct contact is difficult to implement in some conditions, so indirect contact sometimes has to fill the gap. Indirect contact can be adopted under segregated situations and strained tensions, to ‘nurture’ future direct contact. Another strategy is social categorization, which has received less support from field studies. Nevertheless, it helps interpret how contact works. Future research could develop some measures to determine the level of intergroup tensions. This helps us to statistically measure how intense intergroup relations are, enabling us to choose more suitable interventions for each case. Another suggestion is for those who implement strategies in reality. Studies showed variability of laboratory and field evidence. Adopting inappropriate methods might result in reversing effects (Paluck & Green, 2009). Therefore, it is of vital importance to thoroughly explore relevant field studies before practical implementation.

References

Allport, G. W., Clark, K., & Pettigrew, T. (1954). The nature of prejudice.

Dovidio, J. F., Love, A., Schellhaas, F. M., & Hewstone, M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: Twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 606-620.

Dovidio, J. F., Eller, A., & Hewstone, M. (2011). Improving intergroup relations through direct, extended and other forms of indirect contact. Group processes & intergroup relations, 14(2), 147-160.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Guerra, R., Hehman, E., & Saguy, T. (2016). A common ingroup identity: Categorization, identity, and intergroup relations.

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2009). A common ingroup identity: A categorization-based approach for reducing intergroup bias.

Hall, N. R., Crisp, R. J., & Suen, M. W. (2009). Reducing implicit prejudice by blurring intergroup boundaries. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 244-254.

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual review of psychology, 53(1), 575-604.

Hewstone, M., Kenworthy, J. B., Cairns, E., Tausch, N., Hughes, J., Tam, T., & Pinder, C. (2008). Stepping stones to reconciliation in Northern Ireland: Intergroup contact, forgiveness and trust. The social psychology of intergroup reconciliation, 199-226.

Hewstone, M., Lolliot, S., Swart, H., Myers, E., Voci, A., Al Ramiah, A., & Cairns, E. (2014). Intergroup contact and intergroup conflict. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 20(1), 39.

Houlette, M. A., Gaertner, S. L., Johnson, K. M., Banker, B. S., Riek, B. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2004). Developing a more inclusive social identity: An elementary school intervention. Journal of Social Issues, 60(1), 35-55.

Johnston, B. M., & Glasford, D. E. (2018). Intergroup contact and helping: How quality contact and empathy shape outgroup helping. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(8), 1185-1201.

Mathew Ingram, 2007, Camp, flickr, https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.flickr.com%2Fphotos%2Fmathewingram%2F882244782&psig=AOvVaw3uVZPkTZ9T3HxCYak5m5o3&ust=1618216917445000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAIQjRxqFwoTCOCS8vrl9e8CFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

Miller, N. (2002). Personalization and the promise of contact theory. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 387-410.

Montecruz Foto, 2021, Ireland: Sectarian riots – a bad end to a bad peace, Maxism

Nier, J. A., Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Banker, B. S., Ward, C. M., & Rust, M. C. (2001). Changing interracial evaluations and behavior: The effects of a common group identity. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4(4), 299-316.

Paluck, E. L., & Green, D. P. (2009). Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annual review of psychology, 60, 339-367.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual review of psychology, 49(1), 65-85.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(5), 751.

Pettigrew, T. F., Christ, O., Wagner, U., & Stellmacher, J. (2007). Direct and indirect intergroup contact effects on prejudice: A normative interpretation. International Journal of intercultural relations, 31(4), 411-425.

Prati, F., Crisp, R. J., & Rubini, M. (2020). 40 Years of Multiple Social Categorization: A Tool for Social Inclusivity. European Review of Social Psychology, 1-41.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of social issues, 41(3), 157-175.

Stiff, C., & Kedra, P. (2020). Playing well with others: The role of opponent and intergroup anxiety in the reduction of prejudice through collaborative video game play. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(1), 105.

Turner, R. N., Hewstone, M., & Voci, A. (2007). Reducing explicit and implicit outgroup prejudice via direct and extended contact: The mediating role of self-disclosure and intergroup anxiety. Journal of personality and social psychology, 93(3), 369.

Wölfer, R., Christ, O., Schmid, K., Tausch, N., Buchallik, F. M., Vertovec, S., & Hewstone, M. (2019). Indirect contact predicts direct contact: Longitudinal evidence and the mediating role of intergroup anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(2), 277.

University of Oklahoma. Institute of Group Relations, & Sherif, M. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment (Vol. 10, pp. 150-198). Norman, OK: University Book Exchange.

Wright, S. C., Aron, A., McLaughlin-Volpe, T., & Ropp, S. A. (1997). The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 73(1), 73.

Related Posts

To safeguard Africa’s topmost predators

From Nepal’s bengal tiger to Kenya’s big Lions, conservation of...

Read MoreHealth Literacy in the United States

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst...

Read MoreAlleviating Vaccine Hesitancy: The Path to a Safer Future

The human mind is constantly working on the fly, adapting...

Read MoreAilin Han