Figure: A typical elementary school classroom in Japan (Cassidy, 2005). Source: Wikimedia Commons, Tony Cassidy

The concept of mental health literacy (MHL) refers to knowledge and beliefs about mental health and mental health disorders (Kutcher et al., 2016). Helping children to develop MHL is critical because awareness of mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders is essential for recognizing them and seeking help. Along with increasing the likelihood of seeking help, the development of MHL is also positively associated with improvements in mental health outcomes, such as the alleviation of mild to moderate depression (Brijnath et al., 2016).

Efforts to increase MHL in children must recognize that mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders often begin in early childhood. A 2016 survey found that 1 in 6 children between the ages of 2-8 reported having a diagnosed mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder (CDC, 2020; Cree, 2018). Furthermore, although many studies of mental health have focused on teenagers, pre-teens (9-12 years old) are a crucial group for early treatment and prevention of mental disorders. The present work aims to highlight a novel educational program for developing MHL in pre-teens, examine the program’s effectiveness, and discuss future directions and considerations.

In an effort to develop MHL in pre-teens, Ojio et al. (2019) designed a school-based, teacher-led program adapted from a previous teacher-led MHL education program for secondary school students. Also designed by Ojio et al. (2015), the previous program was successful in increasing knowledge about mental health and getting students to recognize mental health problems and seek help. These improvements were seen immediately after the program and remained effective three months after the program ended based on questionnaires administered to the participants at those two time points. The program for pre-teens designed by Ojio et al. (2019) focused on similar topics, including the prevalence of mental disorders, lifestyle associations with mental health, and seeking help from adults. Their program consisted of a single 45-minute session where topics were presented to students by teachers through a 10-minute animated film. Participants were fifth- and sixth-grade students from schools around Tokyo, Japan, and consent was obtained from students and their parents (Ojio et al., 2019).

Like their earlier study, Ojio et al. (2019) examined the effectiveness of the MHL education program among their participants by administering questionnaires to students before the program, at the end of the session, and three months after the session. The questionnaires contained items asking about students’ knowledge regarding mental health and illnesses, recognizing mental health conditions, and seeking help for themselves and others (Ojio et al., 2019). They found that, overall, students showed significant improvements in their questionnaire scores for all topics after the session except for two topics: recognizing when to seek help (no improvement across any time points) and intention to seek help for themselves (improvement was seen immediately after the session but was not seen three months after).

This study, according to the authors, was the first to demonstrate the effectiveness of a school-based teacher-led program for developing MHL in pre-teens. In conjunction with the success of the teacher-led program for secondary students designed by Ojio et al. (2015), these results support the use of a teacher-led program to increase MHL in students across a broad range of ages. The implementation of such a program would help address some of the shortcomings in child and adolescent mental health services, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. According to a review by Juengsiragulwit (2015), such shortcomings include inadequate funding, overloaded services, and a lack of medical health professionals in school settings. The teacher-led MHL program can mitigate the consequences of these challenges, as the sessions are brief and can be administered by school teachers after a 2-hour training session instead of requiring a mental health professional (Ojio et al., 2019). Furthermore, future studies can expand on the limitations of the Ojio study by including a control group (that does not receive MHL intervention), controlling for factors such as socioeconomic status, or performing the study in other countries. These studies can also focus on the two topics where improvements were not observed: students’ ability to recognize when to seek help and their intention to seek help for themselves. These topics offer opportunities to tweak and refine the intervention and improve MHL outcomes. To conclude, the school-based teacher-led MHL education program developed by Ojio et al. (2019) is a promising, accessible, and effective way of increasing MHL in pre-teens.

References

- Brijnath, B., Protheroe, J., Mahtani, K. R., & Antoniades, J. (2016). Do Web-based Mental Health Literacy Interventions Improve the Mental Health Literacy of Adult Consumers? Results From a Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e5463. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5463

- Cassidy, T. (2005). A typical classroom in a Japanese elementary school.Elementary School- Japan. Flickr. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JapaneseClassroom2.jpg

- CDC. (2020, June 15). Data and Statistics on Children’s Mental Health | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html

- Cree, R. A. (2018). Health Care, Family, and Community Factors Associated with Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders and Poverty Among Children Aged 2–8 Years—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6750a1

- Juengsiragulwit, D. (2015). Opportunities and obstacles in child and adolescent mental health services in low- and middle-income countries: A review of the literature. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 4(2), 110–122.

- Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental Health Literacy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 61(3), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609

- Ojio, Y., Foo, J. C., Usami, S., Fuyama, T., Ashikawa, M., Ohnuma, K., Oshima, N., Ando, S., Togo, F., & Sasaki, T. (2019). Effects of a school teacher-led 45-minute educational program for mental health literacy in pre-teens. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(4), 984–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12746

- Ojio, Y., Yonehara, H., Taneichi, S., Yamasaki, S., Ando, S., Togo, F., Nishida, A., & Sasaki, T. (2015). Effects of school-based mental health literacy education for secondary school students to be delivered by school teachers: A preliminary study. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 69(9), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12320

Related Posts

Early Childhood Adversity Impacts Impulsive Decision-Making

Cover Image: An image of a girl holding a stuffed...

Read MoreBad dreams? According to new studies, COVID-19 could be to blame

Figure 1: A sleeping child. When we sleep, we dream,...

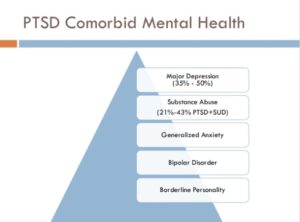

Read MoreBrain Circuit Disorders in PTSD

Figure 1: PTSD and its comorbid mental health symptoms contribute...

Read MoreUniversality of the Face: New Research Points to a Shared Human Commonality in Emotional Expression

Figure 1: Examples of emotional expressions Source: Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels Raising...

Read MoreThe Cognitive Aspects Behind Computer Code Comprehension

Figure 1: A section of a python code program. Programming...

Read MoreVincent Lai