Cover Image: An image of a girl holding a stuffed animal bear. (Source: Pixabay, Skitterphoto)

Introduction

Early childhood adversity can involve a variety of negative exposures, ranging from physical and sexual abuse to chronic poverty (Anda et al., 2006; Burghy et al., 2012; Cohen et al., 2013). Evidence from population-based epidemiological studies have found that childhood adversity has significant detrimental impacts on an individual’s well-being (Cohen et al., 2001; Green et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2012). People unluckily exposed to early childhood adversity are at elevated risk of developing severe mental disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorders, etc.) and self-destructive behaviors (alcoholism, substance use, etc.) (Barrett, 2009; Molnar et al., 2001; Troy et al., 2021).

Another negative consequence of early childhood adversity is impulsivity and, more specifically, impulsive decision-making. One meta-analysis (a study of existing studies) found that chaos in the household was inversely associated with child executive functioning and effortful control (Andrews et al., 2021). However, other recent research has found that early childhood adversity could enhance individuals’ executive functioning and result in adaptive strategies – a seeming contradiction. Identifying the factors that lead to these two different outcomes may explain why some people cope with more resilience and others with more vulnerability

In this article, I focus on the association between childhood adversity and impulsive decision-making, traumas that occur in early childhood, and their impact that accumulates during childhood development. The contradictory findings mentioned above will also be compared and discussed.

Early Childhood Adversity

Early adversity refers to a condition that threatens the satisfaction of needs and main goals of the individual, constrains their development, and leads to prolonged stress (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995). Adverse childhood experiences that occur before 18 can be broken down into three categories: (1) abuse, including emotional, physical, and sexual; (2) neglect, including emotional and physical; and (3) household dysfunction, including interpersonal violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, and incarceration of a household member (Lukasse et al., 2009).

Other researchers have further divided childhood adversity into two parts: experiences of deprivation and experiences of threat (McLaughlin et al., 2012). Deprivation is the absence of positive cognitive and social inputs. Threats, on the other hand, include events that involve actual or threatened death, serious injury, sexual violation, or other harm to one’s physical integrity. Researchers also may refer to complex exposures, or experiences that involve both threat and deprivation, which happen in many cases.

Early childhood is a sensitive period in human development, during which the brain, especially the circuitry related to emotion, attention, self-control, and stress, is shaped by the interplay of genetic information in the child’s genes and their lived experiences. According to developmental and evolutionary theory, biological systems, such as the reward system, show considerable functional plasticity (adaptability) early in development, making them highly malleable in the face of changing environmental conditions (Meaney et al., 2010). As children grow, the biological and environmental factors that determine their development become increasingly intertwined. Thus, early adversity and later developmental health are linked through the structural and functional development of specific brain and nervous system circuits, from those dealing with executive function to those governing responses to stress.

Take this study for example. One group of researchers, studying an area of the brain called the amygdala that is heavily involved in the experience of emotions, have identified a critical point in childhood development for the experience of adversity They found that healthy adults first exposed to early adversity between the ages of 3 and 7, which is an important period for amygdala development, show greater cortisol awakening response in the amygdala relative to those first exposed to early adversity before 3 or after 7 (Flaherty et al., 2006).

Adverase childhood experiences that influence children’s development typically do not only include one-time, dramatic events; the daily, repeated events in a child’s life are often much more important. It is the chronic, day-to-day exposure to maltreatment, poor parenting, and other adversities, rather than an individual, dramatic occurrence of abuse, which causes the most damage to developmental health. Also, prior research has shown that different types of adverse experiences frequently co-occur, and most individuals exposed to childhood adversity have experienced multiple adverse experiences (Finkelhor et al., 2007; McLaughlin et al., 2012).

Even though adverse childhood events occur early in life, victims’ reactions tend to be subsequently kept and reinforced through a series of differential exposures to stressful and risky social contexts. For example, cognitive theory (Beck, 1976; Young et al., 2003) and attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) both posit that negative experiences in childhood are internalized and continue to shape how the child responds to external events as they age. Those with exposure to childhood adversity and negative circumstances are more likely to continue to be exposed to – and even be drawn towards – stressful events and circumstances (Pearlin, 1989).

The Impact of Early Childhood Adversity

Study suggested that there is a bilateral relationship between childhood adversity and impulsivity. Childhood maltreatment leads to an elevated risk of individual impulsivity, which, in turn, results in greater subsequent maltreatment (Gershoff et al., 2002; Vasta et al., 1982). To disentangle and break this vicious circle, we would first explore how childhood maltreatment impacts individuals’ life.

Maltreatment events during childhood have deleterious effects later in life, including impulsive decision-making. Impulsive decision-making (or impulsive choice) refers to decisions based on evaluation of potential outcomes (i.e., risks and rewards) and is associated with the tendency to favor more immediate rather than delayed rewards (Demons et al., 2016; Broos et al., 2012). Two types of tasks are frequently used to assess impulsive decision-making. One is the Delay Discounting Task (DDT), which measures impulsive decision-making as a participant’s tendency to choose smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. The other is the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART), which models real-world risk behavior through the conceptual frame of balancing the potential for reward versus loss (Lejuez et al., 2002). For example, Delay discounting task was applied in both humans (Levitt et al., 2021; Acheson et al., 2019) and rats (Brydges et al., 2015). Similar findings showed that subjects with early adverse experiences made worse performance. Euser et al. (2013) assessed event-related potentials during a modified version of the Ballon Analogue Risk Task in adolescents with a parental history of substance use disorders. The results showed that high-risk male adolescents made significantly more risky and faster decisions than did non-risk controls.

The link between adversity experienced early in development and increased impulsivity and reward incentive salience has been demonstrated in both animals and humans (Chugani et al., 2001). In animal models, maternal separation and isolated rearing increase impulsivity and hyperactivity. Adult rodents who, as pups, were separated from their mother show greater impulsivity, sensitivity to rewards, and behavioral inflexibility compared to adults who were reared naturally (Hall et al., 1998; Lovic et al., 2011). In humans, exposure to adversity early in life is associated with heightened ADHD symptoms, including greater impulsivity and hyperactivity (Laucht et al., 2007).

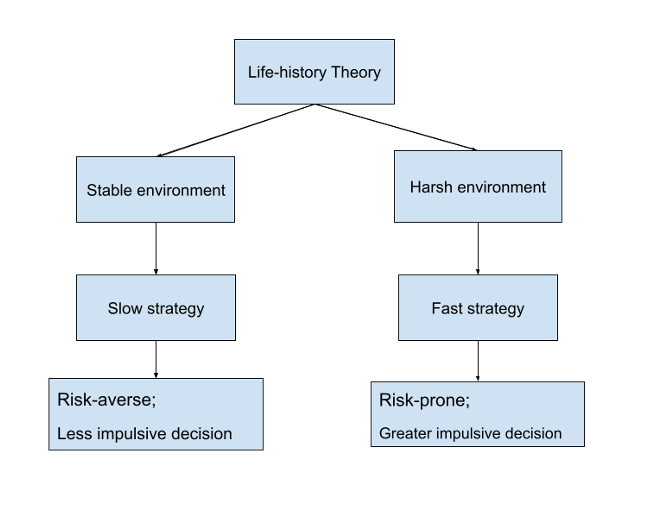

Although the relation between childhood maltreatment and impulsive decision making is well-established, further explanation of how this occurs is still needed. There are some theories on the matter. Life-history theory posits that organisms strategically allocate resources to different events and circumstances across their life span (Belsky et al. 2012; Belsky et al. 1991; Del Giudice et al. 2011; Ellis et al. 2009). Since these resources are finite by nature, it is impossible to maximally devote them to all major life functions. Thus, there is a trade-off. Natural selection favors individuals who can arrange development and activities, in other words, allocate resources, in a way that optimizes the trade-off between life course and different ecological conditions (Belsky et al. 2012). These strategies exist on a fast-slow continuum. People who adopt slower strategies tend to have high expectations and are relatively risk-averse because they have to survive to realize their expectations. Thus, they are characterized by later reproductive development and behavior, preferences toward relatively stable pair bonds, higher quality parental investment, and fewer offspring. Conversely, people reared in a harsh environment usually adopt the fast strategy, which is high-risk, impulsive, and prioritizes immediate over delayed rewards (Del Giudice et al. 2011; Ellis et al., 2014). They have low expectations with regards to future resource availability and are relatively risk-prone because they have little to lose. However, it is also worth noting that whether impulsivity is adaptive in harsh environments depends on the nature of the early life environment to which a person has been exposed.

Figure 1: This image shows two types of life history strategies. Type one is the slow strategy, typical of a relatively stable environment; type two is the fast strategy, typical of a relatively harsh environment. (Source: Image Drawn by author, based on Belsky et al. 2012)

Apart from evolutionary and life course perspectives, other researchers have suggested that childhood adversity is related to maladaptive schema, such as themes with danger. Danger schemas facilitate the biased processing of threat-relevant information. That is, danger schemas influence the manner in which individuals allocate their attentional resources, interpret ambiguous material, and recall experiences with threat. It was found that people who act on the danger schema prefer smaller immediate rewards over larger future rewards (Brezina et al., 2009). In other words, they act more impulsively. This kind of impulsivity is understandable because future rewards are much more uncertain in dangerous and constantly changing environments.

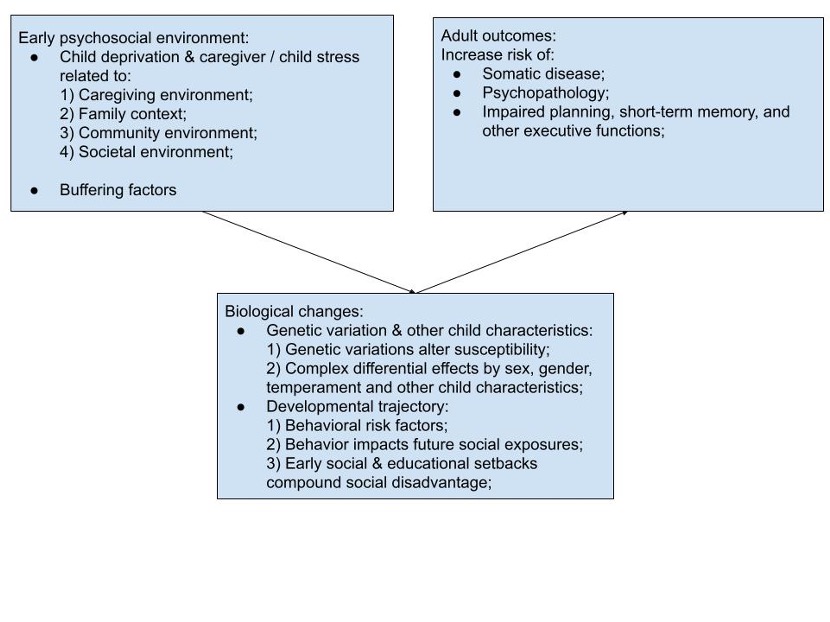

A Neurobiological approach adds more evidence to support these theories of childhood adversity by examining their underlying physical mechanisms. Research suggests that impulsivity results from the impacts of early adversity on multiple integrated biological systems mediated by the brain (Pakulak et al., 2018). Some researchers hypothesize that childhood adversity alters neurobiological and psychosocial processes, which in turn may affect decision making (Heim et al., 2002; Kendler et al. 2004). For example, Gassen et al. (2019) proposed a novel theoretical model linking impulsive decision-making to the activities of the immune system. They found that inflammation may contribute to decision-making patterns. Other studies found that adverse childhood experiences can disrupt normal neural development, particularly in prefrontal cortical regions that govern response inhibition (Blair & Raver 2016; Hart and Rubia 2012; Pechtel & Pizzagalli 2011). Dysfunction in the anterior cingulate cortex is also a marker of childhood maltreatment, which also may be linked with impulsivity later in life (Lutz et al. 2017; Turecki 2005). Adversity has been linked to a variety of alterations in reward processing, including both potentiated and attenuated motivation to approach prospective rewards.

Figure 2: Conceptual model illustrates how early psychosocial adversity impacts adult outcomes. (Source: Image Drawn by author based on Berens et al., 2017)

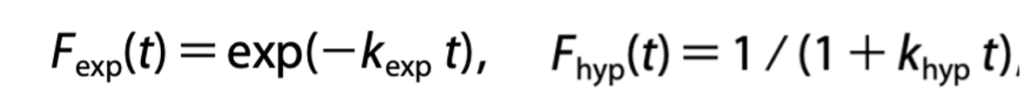

Theoretical and empirical studies have been trying to disentangle the association between childhood adversity and later impulsive decisions. To advance our understanding in this field, mathematical models or formula could be generated to predict the trajectory or patterns in the impact of childhood adversity. For example, during the last several decades, substantial progress has been made in uncovering the basic mechanisms of impulsive decision making, with theoretical models such as exponential or hyperbolic discount function being built (Kim & Lee, 2011). These two discount functions consist of a temporal discount function, F(t), which describes how steeply the value of delayed reward decreases with its delay t.

Exponential and hyperbolic discount function are given by the following respectively:

Based on these models, behavioral studies further found that patients with substance abuse tend to display steeper discount functions (Vuchinich & Simpson, 1998; Mitchell, 1999), indicating that such maladaptive behaviors arise from impulsive choices. However, decision-making models that consider childhood maltreatment is still needed in the future.

The Contradictory Findings

While early childhood adversity is a potential vulnerability factor for later impulsivity, not everyone who experiences adversity will go on to develop this reaction pattern. It is known that childhood trauma is strongly associated with executive dysfunction and impulsivity (Narvaez et al., 2012), and greater impulsivity is related to deficits in executive function. However, some researchers have argued that childhood adversity may shape cognition in adaptive ways rather than impairing cognitive function (Mittal et al., 2015; Ellis et al., 2019). Based on evolutionary models of behavior, adverse childhood environments can enhance specific types of cognitive performance in the face of uncertainty (Belsky et al., 1996; Ellis & Del Giudice, 2014; Frankenhuis & Del Giudice, 2012; Hawley, 2011; Nederhof & Schmidt, 2012).

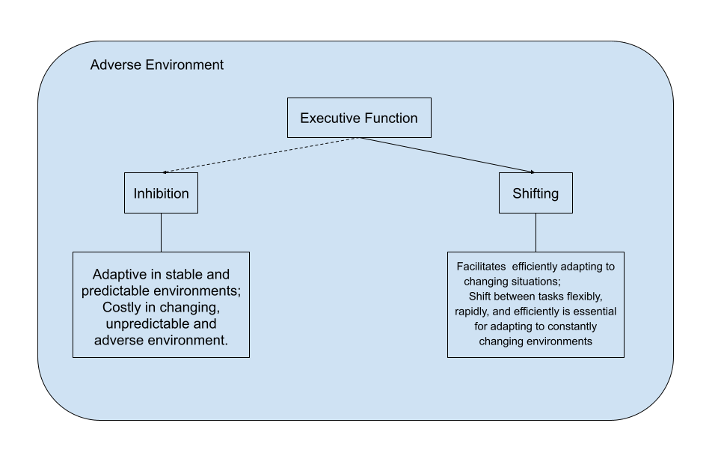

Mittal et al. (2015) measured executive function while participants took part in two tasks: inhibition (overriding dominant responses) and shifting (efficiently switching between different tasks). They found that people with negative childhood experiences performed worse at inhibition, but better at shifting, which is especially useful in an unpredictable environment. Inhibition is the deliberate overriding of dominant responses. It reflects the ability to exert active, intentional control to maintain and pursue a single goal (Mittal et al., 2015). Inhibition is essential for pursuing long-term goals and delaying gratification, which makes it adaptive in stable and predictable environments in which long-term investments are more likely to pay off. Shifting is the ability to shift between goals or strategies, and it facilitates efficiently adapting to changing situations. Opportunities in this environment are fleeting, and individuals who can adapt to change by quickly identifying new patterns and associations should be able to make better use of new opportunities before they disappear. Thus, exposure to harsh or unpredictable early life environments should enhance shifting. Inhibition, on the contrary, can be costly in constantly changing, unpredictable environments because it prevents people from taking advantage of important, short-term opportunities (Daly & Wilson, 2005). People who are good at shifting are better at allowing their responses to be guided by the current situation rather than by an internal goal.

Figure 3: Adverse early life environments have specific and opposing effects on inhibition and shifting. Harsh or unpredictable early life environments might impair inhibition and enhance shifting. (Source: Drawn by author based on Mittal et al., 2015)

Generally, we assume that early childhood adversity results in a greater degree of risk-taking behaviors such as alcohol mis-use, drug abuse, or anti-social behavior. Research has upheld this intuition on a large scale (Molnar et al., 2001). However, Kopetz et al. (2019) experimentally studied the impact of early psychosocial deprivation on risky behaviors, and they postulated on the contrary that early psychosocial deprivation could reduce adolescent risk-taking due to its diminishing effects on reward sensitivity. They explained that risky behavior is enacted to fulfill individual motivations and, thus, must be supported by enhanced executive function. Early psychosocial deprivation decreased engagement in risk-taking among young adolescents by reducing motivation related to impulsive behavior. This impact was further reduced by its deleterious effects on executive control. Since early childhood adversity leads to decreased executive function, there may be less exhibition of risky behaviors. In light of this, those with early adverse experiences may conduct less impulsive decision-making.

It is important to re-state that the study conducted by Mittal et al. (2015), discussed two paragraphs prior, found enhanced executive function, more specifically in people who experienced early childhood adversity – this is directly at odds with the results of Kopetz et al. (2019). How can this be? It turns out that the two teams measured different dimensions of executive function and used different experimental situations. More specifically, in Mittal’s study, they focused on the shifting aspect of executive function in harsh or unpredictable environments, while Kopetz and colleagues on the executive control side in foster care context. We should also be aware of the aspects or dimensions of impulsivity being studied. For example, impulsive decision-making can be divided into ideation, choices, or action. Mittal et al. (2015) looked impulsive deciison making more from the choices perspective, while Kopetz et al. (2019) more from the action perspective. After all, the dimension of key variables studied determines how experiments are designed and conducted, and how the experimental results are analyzed. The outcomes might be in conflict if we apply different angles.

Another reason for the discrepancy between studies may be that they are focused on different forms of adversity. Kopatz’s research studied institutional rearing, while other studies on disadvantaged neighborhoods, dysfunctional families, and experiencing discrimination (Carver et al., 2011). Additionally, the age of the study sample calls for extra attention. Kopatz’s study used adolescents of 12 – other studies have focused on different age groups.

To sum up, we conclude that the following factors that may lead to inconsistent findings. 1. The aspects of key variables (childhood adversity and impulsive decision making) of interest, such as forms, onset age, duration and severity of adversity, and impulsive decision in ideation and action. 2. Samples from diverse backgrounds (i.e., age, culture, race, etc.). 3. Experiment design, conditions, and measurement. By better understanding how and why research findings differ, we gain the ability to build targeted interventions for individuals in different circumstances.

Conclusion and Discussion

Although it is well documented that childhood adversity correlates with impulsivity, support for a causal relationship between childhood maltreatment and later impulsive decisions in a controlled, measured laboratory setting is generally lacking, especially in human studies. Most studies have focused on related terms such as risky behaviors, self-control/regulation, and reward processing. However, self-control/regulation and reward processing can only help indicate whether there will be impulsive decision-making, and they are situationally dependent. Future research, ideally research conducted with prospective, longitudinal designs (i.e., studies that look at the after-effects of exposure to childhood adversity on individual patients over time), needs to address this gap.

Intricate models that explain the biological causes underlying the link between adverse childhood experiences and impulsive decision making are needed in the future. Current research primarily focuses on the subset of the population already diagnosed with mental illnesses such as major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, personality disorders, and ADHD. Future research needs to expand to a more general population, observing their daily choices and actions, to get a full picture of how childhood adversity impacts impulsivity absent other underlying psychological conditions. Moreover, the influence of childhood adversity may manifest in different forms over the course of development. An integrative and dynamic framework is needed, especially in longitudinal studies.

Identifying developmental processes that are disrupted by childhood adversity is the key to developing better intervention strategies for children prone to impulsive decision-making. This would reduce the socioeconomic costs of such decision-making patterns to the individual and society. Effective intervention for those children still needs to be tried and tested in a longitudinal study with follow-up investigations. Although exposure to early adversity is a significant predictor of later problems, they are not inevitable for all children. Children who are more prone to impulsivity may also experience the most gains from timely intervention.

References

- Acheson, A., Vincent, A. S., Cohoon, A., & Lovallo, W. R. (2019). Early life adversity and increased delay discounting: Findings from the Family Health Patterns project. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(2), 153-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pha0000241

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Ch, W., Perry, B. D., ShR, D., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood : A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174-86. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/enduring-effects-abuse-related-adverse/docview/214162294/se-2?accountid=48841

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174-186. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/enduring-effects-abuse-related-adverse/docview/67908619/se-2?accountid=48841

- Andrews, K., Atkinson, L., Harris, M., & Gonzalez, A. (2021). Examining the effects of household chaos on child executive functions: A meta-analysis.Psychological Bulletin, 147(1), 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000311

- Baker, L. M., Williams, L. M., Korgaonkar, M. S., Cohen, R. A., Heaps, J. M., & Paul, R. H. (2013). Impact of early vs. late childhood early life stress on brain morphometrics. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 7(2), 196-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11682-012-9215-y

- Barrett, B. (2009). The impact of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of childhood adversity on adulthood parenting. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 18(5), 489-512. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10538710903182628

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

- Belsky, J., Steinberg, L., & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: an evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647–670.

- Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., & Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48, 662–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024454.

- Blair, C. B., & Raver, C. C. (2016). Poverty, stress, and brain develop- ment: new directions for prevention and intervention. Academic Pediatrics, 16, S30–S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.01. 010.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. I. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Brezina, T. (2009). ACCOUNTING FOR VARIATION IN THE PERCEIVED EFFECTS OF ADOLESCENT SUBSTANCE USE: STEPS TOWARDS A VARIABLE REINFORCEMENT MODEL*. Journal of Drug Issues, 39(3), 443-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002204260903900301

- Broos, N., Schmaal, L., Wiskerke, J., Kostelijk, L., Lam, T., Stoop, N., Weierink, L., Ham, J., de Geus, E.,J.C., Schoffelmeer, A. N. M., van den Brink, W., Veltman, D. J., de Vries, T.,J., Pattij, T., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2012). The relationship between impulsive choice and impulsive action: a cross-species translational study. PloS One, 7(5), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036781

- Brydges, N. M., Holmes, M. C., Harris, A. P., Cardinal, R. N., & Hall, J. (2015). Early life stress produces compulsive-like, but not impulsive, behavior in females. Behavioral Neuroscience, 129(3), 300-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bne0000059

- Burghy, C. A., Stodola, D. E., Ruttle, P. L., Molloy, E. K., Armstrong, J. M., Oler, J. A., Fox, M. E., Hayes, A. S., Kalin, N. H., Essex, M. J., Davidson, R. J., & Birn, R. M. (2012). Developmental pathways to amygdala-prefrontal function and internalizing symptoms in adolescence. Nature Neuroscience, 15(12), 1736-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn.3257

- Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., Joormann, J., Kim, Y., & Nam, J. Y. (2011). Serotonin transporter polymorphism interacts with childhood adversity to predict aspects of impulsivity. Psychological Science, 22(5), 589-595. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797611404085

- Chugani, H. T., Behen, M. E., Muzik, O., Juhász, C., Nagy, F., & Chugani, D. C. (2001). Local Brain Functional Activity Following Early Deprivation: A Study of Postinstitutionalized Romanian Orphans. NeuroImage, 14(6), 1290-1301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0917

- Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1995). A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(5), 541-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008

- COHEN, P., BROWN, J., & SMAILES, E. (2001). Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Development and Psychopathology, 13(4), 981-99. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/child-abuse-neglect-development-mental-disorders/docview/201696093/se-2?accountid=48841

- Cross, D., Fani, N., Powers, A., & Bradley, B. (2017). Neurobiological development in the context of childhood trauma: Science and Practice. Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 111-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12198Danese, A., & Lewis, S. J. (2017). Psychoneuroimmunology of early-life stress: The hidden wounds of childhood trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 99-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.198

- Del Giudice, M., Ellis, B. J., & Shirtcliff, E. A. (2011). The Adaptive Calibration Model of stress responsivity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(7), 1562-1592. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.11.007

- Demos, K. E., Hart, C. N., Sweet, L. H., Mailloux, K. A., Trautvetter, J., Williams, S. E., Wing, R. R., & McCaffery, J. M. (2016). Partial sleep deprivation impacts impulsive action but not impulsive decision-making. Physiology & Behavior, 164, 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.06.003

- Ellis, B. J., & Del Giudice, M. (2019). Developmental adaptation to stress: An evolutionary perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 111-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011732

- Ellis, B. J., & Del Giudice, M. (2014). Beyond allostatic load: rethinking the role of stress in regulating human development. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0954579413000849.

- Euser, A. S., Greaves-Lord, K., Crowley, M. J., Evans, B. E., Huizink, A. C., & Franken, I. H. A. (2013). Blunted feedback processing during risky decision making in adolescents with a parental history of substance use disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4), 1119-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000412

- Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology, 19(1), 149-66. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/polyvictimization-trauma-national-longitudinal/docview/201698758/se-2?accountid=48841

- Flaherty, E. G., Thompson, R., Litrownik, A. J., Theodore, A., & al, e. (2006). Effect of Early Childhood Adversity on Child Health. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(12), 1232-8. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effect-early-childhood-adversity-on-child-health/docview/198446906/se-2?accountid=48841

- Frankenhuis, W. E., & Del Giudice, M. (2012). When do adaptive developmental mechanisms yield maladaptive outcomes? Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025629

- Gassen, J., Prokosch, M. L., Eimerbrink, M. J., Proffitt Leyva Randi, P., White, J. D., Peterman, J. L., Burgess, A., Cheek, D. J., Kreutzer, A., Nicolas, S. C., Boehm, G. W., & Hill, S. E. (2019). Inflammation Predicts Decision-Making Characterized by Impulsivity, Present Focus, and an Inability to Delay Gratification. Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group), 9(1) http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41437-1

- Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579.

- Hall, W., & Solowij, N. (1998). Adverse effects of cannabis. The Lancet, 352(9140), 1611-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1

- Hart, H., & Rubia, K. (2012). Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 52. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00052.

- Hawley, P. H. (2011). The evolution of adolescence and the adolescence of evolution: The coming of age of humans and the theory about the forces that made them. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 307-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00732.x

- Jensen, S. K. G., & Nelson,Charles A., I.,II. (2017). Biological embedding of childhood adversity: from physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC Medicine, 15http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0895-4

- KENDLER, K. S., KUHN, J. W., & PRESCOTT, C. A. (2004). Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women.Psychological Medicine, 34(8), 1475-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003329170400265X

- Keyes, K. M., Eaton, N. R., Krueger, R. F., McLaughlin, K. A., Wall, M. M., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. S. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(2), 107-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062

- Kim, J. H., & Ji, Y. C. (2020). Influence of childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms on impulsivity: focusing on differences according to the dimensions of impulsivity. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1) http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1796276

- Kim, S., & Lee, D. (2011). Prefrontal cortex and impulsive decision making. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12), 1140-1146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.005

- Kopetz, C., Woerner, J. I., MacPherson, L., Lejuez, C. W., Nelson, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., & Fox, N. A. (2019). Early psychosocial deprivation and adolescent risk-taking: The role of motivation and executive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(2), 388-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000486

- Laucht, M., Hohm, E., Esser, G., Schmidt, M. H., & Becker, K. (2007). Association between ADHD and smoking in adolescence: shared genetic, environmental and psychopathological factors. Journal of Neural Transmission, 114(8), 1097-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00702-007-0703-y

- Lejuez, C. W., Read, J. P., Kahler, C. W., Richards, J. B., Ramsey, S. E., Stuart, G. L., Strong, D. R., & Brown, R. A. (2002). Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 8(2), 75-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-898X.8.2.75

- Levitt, E. E., Amlung, M. T., Gonzalez, A., Oshri, A., & MacKillop, J. (2021). Consistent evidence of indirect effects of impulsive delay discounting and negative urgency between childhood adversity and adult substance use in two samples. Psychopharmacology, 238(7), 2011-2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00213-021-05827-6

- Lovic, V., Keen, D., Fletcher, P. J., & Fleming, A. S. (2011). Early-life maternal separation and social isolation produce an increase in impulsive action but not impulsive choice. Behavioral Neuroscience, 125(4), 481–491. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024367

- Lukasse, M., Schei, B., Vangen, S., & Øian, P. (2009). Childhood abuse and common complaints in pregnancy. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 36(3), 190-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00323.x

- Lutz, P.-E., Tanti, A., Gasecka, A., Barnett-Burns, S., Kim, J. J., Zhou, Y., Chen, G. G., Wakid, M., Shaw, M., Almeida, D., Chay, M. A., Yang, J., Larivière, V., M’Boutchou, M. N., van Kempen, L. C., Yerko, V., Prud’homme, J., Davoli, M. A., Vaillancourt, K., Théroux, J. F., Bramoullé, A., Zhang, T. Y., Meaney, M. J., Ernst, C., Côté, D., Mechawar, N., & Turecki, G. (2017). Association of a history of child abuse with impaired myelination in the anterior cingulate cor- tex: convergent epigenetic, transcriptional, and morphological evi- dence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 1185–1194. https://doi. org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16111286.

- Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the Biological Definition of Gene × Environment Interactions. Child Development, 81(1), 41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01381.x

- Mitchell, S. H. (1999). Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 455-464. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/measures-impulsivity-cigarette-smokers-non/docview/69243938/se-2?accountid=48841

- Mittal, C., Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Sung, S., & Young, E. S. (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(4), 604–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000028

- MOLNAR, B. E., BERKMAN, L. F., & BUKA, S. L. (2001). Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychological Medicine, 31(6), 965-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701004329

- Molnar, B. E., Buka, S. L., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 753-60. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/child-sexual-abuse-subsequent-psychopathology/docview/215104419/se-2?accountid=48841

- Narvaez, J. C. M., Magalhães, P. V. S., Trindade, E. K., Vieira, D. C., Kauer-Sant’Anna, M., Gama, C. S., von Diemen, L., Kapczinski, N. S., & Kapczinski, F. (2012). Childhood trauma, impulsivity, and executive functioning in crack cocaine users. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(3), 238–244. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.058

- Nederhof, E., Belsky, J., Ormel, J., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2012). Effects of divorce on Dutch boys’ and girls’ externalizing behavior in Gene × Environment perspective: Diathesis stress or differential susceptibility in the Dutch Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey study? Development and Psychopathology, 24(3), 929-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000454

- O’Daly, M., Meyer, S., & Fantino, E. (2005). Value of conditioned reinforcers as a function of temporal context. Learning and Motivation, 36(1), 42-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2004.08.00

Pakulak, E., Stevens, C., & Neville, H. (2018). Neuro-, cardio-, and immunoplasticity: Effects of early adversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 131-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044115

Pearlin, L. I., Jacobson, D., & al, e. (1989). The Sociological Study of Stress.Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30(3), 241-56 https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/sociological-study-stress/docview/201659323/se-2?accountid=48841

Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214, 55–70. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s00213-010-2009-2.

Troy, D., Russell, A., Kidger, J., & Wright, C. (2021). Childhood psychopathology mediates associations between childhood adversities and multiple health risk behaviours in adolescence: Analysis using the alspac birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13379

Turecki, G. (2005). Dissecting the suicide phenotype: The role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 30, 398–408.

Vasta, R. (1982). Physical child abuse: a dual-component analysis. Developmental Review, 2, 125–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273- 2297(82)90007-7.

Vuchinich, R. E., & Simpson, C. A. (1998). Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6(3), 292-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.6.3.292

Vythilingam, M., Heim, C., Newport, J., Miller, A. H., & al, e. (2002). Childhood trauma associated with smaller hippocampal volume in women with major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(12), 2072-80. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/childhood-trauma-associated-with-smaller/docview/220132695/se-2?accountid=48841

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Related Posts

COVID-19 May Inflict Lasting Damage on the Central Nervous System

Figure 1: Transmission electron microscope image of the SARS-CoV-2 virus....

Read MoreThe Biochemistry and Broad Utility of Pfizer’s New COVID-19 Drug: Paxlovid

A photo of a Pfizer facility in Italy. (Image Source:...

Read MoreGeopolymer Cement: Upscaling Industrial Waste into Sustainable Alternatives to Portland Cement

Figure 1: Aerial view of the 1.1 billion gallons of...

Read MoreStudy Reveals the Prefrontal Cortex is a Key Conductor in Sleep Regulation

Source: Laboratoires Servier, (CC BY-SA 3.0) Sleep is a fundamental...

Read MoreInvestigating the Quality of Healthcare in Rural Areas

Cover Image: A rural Metro ambulance in Memphis, Tennessee. Rural...

Read MoreTransgender Health Disparities in Prisons

Transgender people are targets for victimization within the prison system...

Read MoreMingcong Tang