The human mind is constantly working on the fly, adapting to situations, and processing new information while considering the old. When posed with opposing courses of action, the best we can do is weigh our options in an attempt to mitigate risk and maximize reward by using what is presented to us along with our past experiences. However, clear cut realities can be blurred and muddled by misleading opinions and emotions. It is at this point that we may make the wrong choice, setting forth a course of events that not only puts the lives of our own children at risk, but the lives of others as well. The decision to vaccinate places us at such a crossroads and for some, the choice is easy: vaccinate. But, for others, it is not so clear. Vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon, yet it poses a great threat and must be dealt with in new and innovative ways.

Since the days of Edward Jenner, the pioneer scientist behind modern vaccination, standard-of-care preventative medicines have been at odds with the resistance, or those who feel the risk of vaccination outweighs the benefit. As medical advances continue to be made, anti-vaccine sentiments follow closely behind, nipping at its coattails. Now, this anti-vaccine mentality does not appear to come from a place of malice but is rooted in an innate parental desire to provide what is believed to be best for children. The mindset of a parent is a peculiar one, especially in this modern era of media and tabloid, with so many questions to be asked and such a variety of answers from sources of information, misinformation, and agenda. Given all the outlets of parental advice, it is easy to become overwhelmed and unsure of the “best way to raise a child.” At this point, in moments of uncertainty, the human mind falls back on heuristics of decision making, capable of bringing about flawed judgement with lasting effects.

When the time comes to balance rational thinking and emotion, it is often easiest to revert to the latter and only rely on instinct. These gut reactions, founded on information that is placed at the forefront of one’s working memory, often fall prey to availability bias. This is of most concern when considering the state of infection transmission in the United States of America. Due to advances in medical technology, vaccination has been deemed one of the most substantial advents in recent history [3] by eradicating or nearly eliminating certain diseases and as such, has greatly diminished the human fear of disease due to lack of exposure. We have become accustomed to life without the threat of fatal infection, and in doing so have relocated our fears elsewhere. In this, vaccines have clearly become victims of their own success. Just as hearing of a rare shark attack can discourage one from enjoying time at a beach, when a parent hears about the chance of an extreme reaction to a vaccine, even if that chance is only one in a million, there are some who choose to go against the physician and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) vaccine recommendations. This is availability bias at work in its most potent form, especially in the modern era: parents haven’t had exposure to the deadly diseases that recommended vaccine series protect against, but they are inundated with information on potential harmful side effects of vaccination. Far too much credence is given to the risks of vaccination when the choice should be clear. This is not to say that we shouldn’t ask questions and voice concerns, but we should ask them with an open mind and engage the factual answers provided by healthcare professionals and government agencies devoted to understanding all there is to know about vaccines. For some, these fears are alleviated by strong physician recommendation, but for other parents, vaccine schedules are altered or forgone completely. At this point, when a parent decides to not vaccinate or delay vaccination, dire downstream effects are put in motion and often other unavoidable measures arise preventing parents from returning with a change of heart about immunization.

There are varying reasons why a parent is unable to initially vaccinate or return to a healthcare provider to vaccinate their child, some of which are legitimate. In a 2013 study of the preceding year, one in three parents voiced some form of concern regarding vaccination [2]. In many cases, there are religious or personal beliefs that prevent families from vaccinating. For example, traditional Amish families do not practice vaccination, and in turn are left more susceptible to preventable disease contraction than other sectors of the population. Over time, vaccines have been deemed “unnatural” and as such strike fear into some of those who prioritize a “natural” lifestyle, resulting in vaccine hesitancy [3]. It seems somewhat inherent to have a general mistrust in the prescribed injection of an unknown solution of chemicals into your child, let alone multiple at once. Without proper understanding of those chemicals, it is not hard to imagine why a parent doesn’t feel comfortable in vaccinating their child. There are also issues related to vaccine access: cost of vaccination, insurance plans of patients, availability of immunization stock and of appointments at clinics. If local providers are unable to administer a vaccination due to inventory and the patient lives a busy lifestyle, unable to return to the clinic in the near future, it is easy for the patient to continue to push off vaccination, leaving themselves and the community at risk for that much longer of a time. Now, there are some individuals who are at great risk from the immune response that is mounted from vaccine administration itself. A fraction of a percent of the population reports that they are unable to receive one vaccine or another due to being immunocompromised or allergic to the vaccine [3]. These are the individuals who have no agency over their susceptibility to disease and are the reason why the rest of the population needs to be vaccinated.

Responsibility to protect those who are medically unable to receive vaccines falls on the shoulders of the general populous. Epidemiologists often cite the basic reproductive number of an infectious disease when discussing the ability to protect non-immunized individuals. Variables considered when scientists determine this are characteristics such as mode of infectivity and estimated levels of immunized host populations. The latter of the two is often known as the degree of herd immunity, a statistical phenomenon that hinges the protection of nonimmune individuals on the likelihood that they will encounter a carrier of disease. Optimally, all individuals would be immunized, but as of the current situation this is not possible. There will always be those with compromised immune systems, allergies, or those who receive a vaccine not of absolute efficacy. Due to this reality, it becomes the duty of the rest of society to act as immunological barriers defending against vaccine preventable diseases to protect at-risk communities. The sentiment of vaccine hesitancy works in stark contrast to forming competent herd immunity, which reinforces the necessity of a nationwide campaign to emphasize the importance of vaccination.

To properly address the crisis of vaccine hesitancy, public opinion must be considered at all fronts. Parents, who only wish to provide the best for their child, are caught in the middle of this turmoil and are at the mercy of the information that they are exposed to, correct or incorrect. The dissemination of well-researched advice must be propagated from all directions toward those who have to make the decision to vaccinate. It is the education system’s responsibility to shed light on the times of immense mortality from disease and emphasize the privilege of vaccination that too many people take for granted. An awareness of the extreme pain and suffering that can be caused by preventable illness must be made to overtake availability bias, which for some, inclines them to overestimate the perceived risks of vaccination. If the public is shown the damage that illnesses can wreak on the human body, hopefully they will be jolted out of their lull of complacency. On another front, physicians and healthcare providers must exercise the power that they wield over public sentiment and be well trained in effectively communicating with patients. The recommendation of health professionals cannot be overstated, but most effective interactions come from a place genuine interaction and care for the patient’s wellbeing and understanding. Healthcare providers must be taught to convey their well-informed knowledge in unambiguous ways so as to leave their patients with an ease of mind in the decision to vaccinate. It must be emphasized that physicians resist the urge to talk down to those who see them and meet their patients from a place of respect. Moreover, the general public needs to be continually reaffirmed in their decision to vaccinate. This support can be provided in the form of persistent research and publication surrounding the efficacy and safety of standard-of-care vaccinations. If studies are done to emphasize the benefits of vaccination and the detriments of low vaccination rates and results of these explorations are made more accessible, then the public can know their health is of utmost concern and be constantly reassured of the decision to vaccinate. These proposals to modify education systems, update healthcare training programs, and publicize cutting edge research in an accessible fashion can be further amplified by instituting changes at the legislative level.

Recent changes in the state of California have shed a great deal of light on the power of government mandates to influence vaccination rates. In the face of decreased vaccination administration by percent of population, California passed measure AB2109 in 2014. This piece of legislation permitted the continued acknowledgement of personal and religious beliefs as excuse for not vaccinating children beginning at kindergarten, yet required physician signature confirming that the risks of not vaccinating were discussed with a parent if they desired to exercise personal belief exemption. Once in effect, a small drop in prevalence of unvaccinated children was observed [3]. Following up, the state of California passed SB277 in 2016 eliminating all exemptions (including religious belief exemptions), except for those medical in nature, upon school entrance. From this legislation, an even more intense drop in prevalence of unvaccinated children upon admittance was observed [3]. An important aspect of the analysis of vaccination rates must be recognized at this point: vaccination rates are measured upon the entrance to kindergarten at age five. This is at an age far older than the maximum age recommended by the CDC for nearly all vaccines. If we want to properly address the vaccine hesitancy crisis, we must analyze it in a way that provides information from the most important demographics.

The measures passed in California set a promising precedent of legislation that when applied nationwide can greatly increase vaccination rates, hopefully to a level that permits acceptable herd immunity for each vaccine preventable disease. However, in response to the passage of SB277, there was an observed spike in parents claiming medical exemption [3]. This indicates that a subset of anti-vaccine parents continued to subvert entrance requirements by finding doctors to sign off on medical exemptions. Knowing this emphasizes the necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration: legislation to require vaccinations and reach appropriate degrees of herd immunity, physicians to act in an ethical manner and not sign off on medical exemptions when they clearly are not the case, all healthcare professionals to provide strong yet compassionate recommendation for vaccination, education systems to reinforce the damage of unchecked disease, and researchers to better publicize the overwhelming benefits to vaccination and to explore demographics of interest.

If these measures are not undertaken, then the grip of vaccine hesitancy will persist. The detriments of an under-vaccinated population have recently been spotlighted in lieu of the most recent measles outbreak and reinforce the need for instituted change. In the decade before 1963, the year the measles vaccine was introduced, it is estimated that 3 to 4 million people in the United States contracted measles each year, 500 of which died from the disease annually [4]. In the year 2000, measles was declared eliminated. Since then, a slight enough decrease in measles vaccine administration has resulted in cases such as the 2014 Disneyland outbreak and the current national outbreak. A disease thought to be eliminated is now reemerging, and those who are not vaccinated have the highest risk of infection [3].As determined in the Disneyland outbreak, and as will likely be the case in the current outbreak, the immensely high degree of international travel puts the United States and essentially every other country at risk of cross contamination from areas of low vaccination and high disease prevalence. Without sufficiently high levels of immunization, there is no other way to effectively resist many vaccine-preventable infections.

By inhabiting a progressing global society, the necessity of vaccination becomes increasingly clear. Fear of minimal threats that vaccines pose must be mitigated through rational discourse to promote their near-universal usage. The much-needed shift in mentality of a select portion of the public can only be achieved through interdisciplinary cooperation. By having all tendrils of government, health, education, and research extend toward public perception of vaccination, appropriate levels of immunity can be reached at a community level and individual lives can be saved.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Ten Great Public Health Achievements. Atlanta.

- Wheeler M. and Buttenheim A. Parental vaccine concerns, information source, and choice of alternative immunization schedules. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Aug 1; 9(8): 1782-1789.

- Jones, M 2017, Vaccine Refusal and Public Health, presentation, Wednesday Nite @ the Lab, University of Wisconsin- Madison, delivered September 27, 2017.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Measles (Rubeola). Atlanta.

Related Posts

Retitling Stress: A Look at the Yerkes-Dodson Law

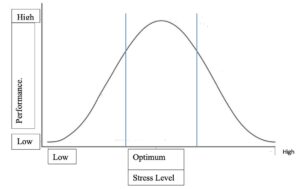

Figure 1: This graph compares stress level with performance at...

Read MoreThe Price of Postponement: The Link Between Procrastination and Sleep Deprivation in Postsecondary Students

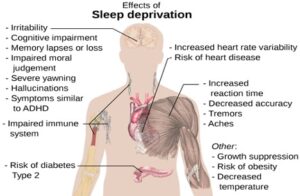

Figure 1: This figure describes the physiological and cognitive effects...

Read MoreBiometrics and Their Health Implications

Source: Torsten Dettlaff Healthcare is constantly evolving. One example of...

Read MoreLuke Zangl and Ryan Brown