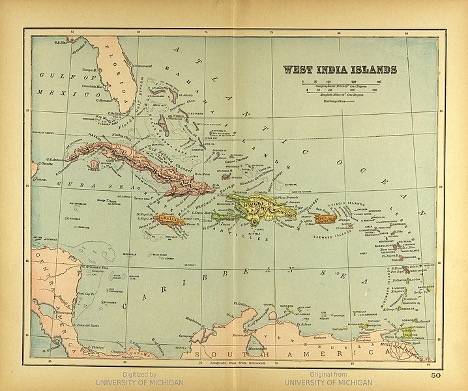

Figure 1: A map of the Caribbean Islands from 1894

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Our ancestors are always with us, especially in our genetic makeup. Looking at the DNA in human remains can help archaeologists piece together the story of migration and diversification in ancient civilizations. In recent studies, the ancient DNA of pre-contact Caribbean individuals were used to re-construct cultural diversification and dispersal of these populations; pre-contact is defined in these studies as before European colonization. The Caribbean is composed of modern-day Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Bahamas, Curaçao, and Venezuela. Approximately 6,000 years ago, humans first inhabited the Caribbean, and around 2,500 years ago, the introduction of ceramics and increased agriculture led to the Ceramic Age (Keegan, 2017). To reflect these cultural shifts in material reliance, Caribbean archaeology defines three main Ages: Lithic, Archaic, and Ceramic. Interestingly, a major genetic shift has been observed between Archaic and Ceramic Age civilizations.

In a recent study, ancient DNA samples from 174 authenticated skeletons were extracted for a genome-wide assessment. These tests found a median of 700,689 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) per skeleton (Fernandes, 2020). SNPs are a singular mutation that differentiates one individual from another. Then based on extracted tools (i.e. stone versus ceramic materials) and radiocarbon dating, the locations were classified as either Archaic or Ceramic Age. Understanding the Age which the skeletons are from will contextualize dispersal and diversification patterns in the Caribbean.

In the Archaic-associated communities, it was discovered that the Greater Antilles islands had the most genetic drift with Indigenous groups from Central and South America. Genetic drift refers to the preference for an allele within a population; a population is more likely to maintain a beneficial allele than a harmful one. When comparing the alleles of the seven language families, there was little to no migratory mating or genetic drift from one language group to another (Fernandes, 2020). A previous study found supporting evidence that Archaic Cuban communities were related to the North America’s Channel Islands of California (Nägele, 2020). However, this could not be replicated in later studies, and there does not appear to be any statistically significant similarities between the genes of Cuba and North America (Fernandes, 2020).

Later, Ceramic users overtook Archaic related ancestry in the Caribbean (with the exception of western Cuba, which maintained relatively homogenous Archaic alleles until European contact). Through ADMIXTURE analysis, a test that analyzes geographic origins of DNA, almost all individuals were traced back to Arawak ancestry (Fernandes, 2020). This supports a single source origin and south to north dispersal pattern where ceramic ancestors moved from Lesser Antilles into Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Across all of the islands, there is evidence for shared alleles, revealing an interconnected population throughout the Caribbean (Fernandes, 2020).

These genetic relationships provide archaeologists evidence for ancient civilizations’ lives and lineages. They also provide a powerful understanding of the pre-contact legacy of Indigenous communities. In fact, 4% to 14% of the genetic makeup of today’s Caribbean people includes varying proportions of Ceramic and Archaic genetic history depending on their geographic location (Fernandes, 2020). Our genomes tell a story of who we are and where we came from, and it is important to remember them.

References

Fernandes, D. M, et al. (2020). A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean. Nature. doi:https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2

Keegan, W.F. & Hofman, C. L. The Caribbean before Columbus (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017)

Nägele, K., et al. (2020). Genomic insights into the early peopling of the Caribbean. Science, Vol. 369 (6502), pp. 456-460. doi:10.1126/science.aba8697

Related Posts

Gut Bacteria May be a Cause of Colorectal Cancer (and the Key to Effective Treatment)

Figure: Cancer cell division is rapid and uncontrollable. New evidence...

Read MoreThe Looming Pandemic of Antimicrobial Resistance

Extensive and irresponsible use of antimicrobial drugs is one of...

Read MoreProteins that Create “Speckles” in Cell Nuclei Discovered

Figure 1: A fluorescent microscopic image of the localization of...

Read MoreKatherine Faulkner