Figure 1: Shows a model for decision making in a social context. Inhibitory spillovers could help facilitate impulse controls thereby resulting in less self-control conflicts

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Choices are an integral part of our lives. According to researchers at Cornell University, we make just above 220 choices when eating, that is, between the start of taking a meal until the end. (Wansick & Sobal, 2007). Choices are usually associated with compromises such that choosing one option foregoes experiencing the benefits of the other choice(s). This opportunity cost is inescapable. Making choices is so significant that behavioral psychology has dedicated a particular field to the study of decision making – behavioral decision theory, which is concerned with the reasoning behind making a particular choice (Takemura, 2020).

Visceral factors, such as sexual desire, hunger, sleep and thirst, are often the driving factors influencing decision making (Loewenstein, 1996). Most visceral states tend to lead to more destructive and impulsive behaviour. As such, most visceral factors often have hedonistic approach attached to them; more often than not, human beings do not act in their best interest when making choices (Loewenstein, 1996). Visceral factors are often associated with a local domain or circuitry in the brain that is responsible for the influence of that particular visceral factor. For instance, the hypothalamus is responsible for sleep and arousal, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is responsible for urination (National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2019; Griffiths & Tadic, 2008). These particular domains are often associated with reward circuits in that the satisfaction of a particular visceral factor is often associated with a particular reward. For example, the dopaminergic reward circuitry releases dopamine not just upon reward, but also when we expect a reward for satisfying a particular visceral factor (Mandal, 2019; Van der Bergh et al., 2008).

It has long been thought that there is no spillover effect in different visceral domains. A spillover effect means that engaging in one action influences the likelihood of commitment to another closely tied behaviour. As a result, spillover effects can either be positive or negative (Nilsson et al., 2016; Elf et al., 2019). It is generally thought that distinct visceral domains cannot spill over to other different domains. For example, the domain responsible for sleep cannot affect the domain responsible for hunger and vice versa. But recent research suggests that this may not be the case.

A team from the University of Twente led by Mirjam A.Tuk investigated the effect of inhibitory spillover (particularly urinary urgency control) in visceral states and its effect on impulse control. They sought to determine if some visceral state domains could spill over to other domains affecting choice, thus making people more rational or less impulsive (Tuk et al., 2011).

The human motivation system can be broadly categorized into 2 systems. The first is the Behavioral Approach System (BAS), which is responsible for our ability to work towards a particular goal through positive reinforcement. For example, one can promote the BAS system in children by offering them candy as a response to doing good things such as cleaning up after themselves. Second, the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) is responsible for alertness to surroundings and allows individuals to attach special value to uncommon events. The BIS is normally associated with punishment rather than reward (Merchán-Clavellino, 2019; Gray, 1981).

Tuk et. al sought to determine if effects of visceral state domains can in fact spill over into other different domains, particularly through inhibition rather than approach as was the norm with previous experiments. They did this through a common inhibition method – suppressing urination urgency as one’s bladder fills with urine (Tuk et al., 2011)

Tuk et. al conducted 4 separate tests to investigate the above question. First, they assessed the participant’s urination urgency (after instructing them to drink a lot of fluids) by testing them on the color-naming component of the Stroop Task, that is, they were instructed to indicate the color of the word in the Stroop Task. (Some words in a Stroop Task are printed in different colors, egg, the word ‘green’ may be printed in red ink – the participants are then instructed to name the color of the word that the word is printed in. In this case, one is supposed to say ‘red’ instead of ‘green’. The color-naming component of the Stroop Task inhibits the dominant or impulsive response (reading) which is called upon in normal situations. For example, it is easier to name ‘green’ than to name the color which ‘green’ is printed in. (Scarpina & Tagini, 2017).

Next, they proceeded to demonstrate how inhibition of urination urgency affected the quality of choices people make. The research team presented their participants with 2 choices. The first choice entailed a smaller reward that they were going to receive the next day and the second choice comprised of a larger reward that they were going to receive later in time.

In the third test, they investigated the relationship between resisting impulsive urges and the sensitivity of the BIS system by manipulating the participants’ urination urgency through bladder control.

Finally, they sought to determine whether inhibitory spillovers are also affected by exogenous cues in addition to physiological cues (bladder control) through prompting one-half of the subjects to search for urination-related words including “water”, “waterfall”, and “pee” and the other half were control subject who searched for non-urination related words (Tuk et al., 2011).

In the first test, the researchers concluded that increased urination urgency results in increased response times in the color-naming aspect of the Stroop task. Next, from the second test, they concluded from the second test that persons with greater urination urgency tend to make better choices, in that those who with an increased urge to urinate chose the long-term reward option. From the third test, they concluded that higher sensitivity of the Behavioral Inhibition System as evidenced by the increased inhibitory task of not voiding urine leads to better decision making. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, they noted found from the fourth test that those who searched for words related to urination reported a greater urge to urinate meaning that exogenous cues could prompt a sense of urination urgency (Tuk et al., 2011).

Admittedly, these results are in stark contradiction to what the researchers expected. Past experiments conducted by Baumeister et al. concluded that the execution of self-control in a particular domain causes impairment of self-control in a sequential domain (Baumeister et al., 2007). However, Tuk argues that since inhibition of urination is largely unconscious, this might make self-control in other domains easier than if the inhibitory process were conscious.

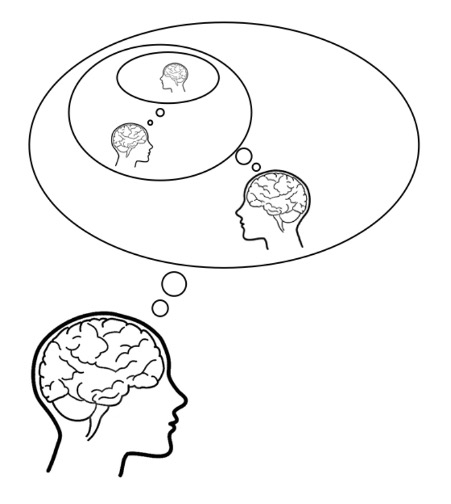

In hindsight, this study is important in that it reflects the powerful impact of inhibition as it relates to impulse control. It opens a new pathway in the field of decision theory, as it is one of the pioneers of the study of inhibition (BIS) rather than activation (BAS) in decision making (Tuk et al., 2011). The fact that people make better decisions when they probe the inhibitory system or domains points to the desired outcome of spillover events. That is, the behavioral domain responsible for registering increasing levels of bladder pressure spills over to the “choice-making domain” of the brain, meaning that the relationship of domains is not only casual but also dependent on each other.

Future research on inhibitory spillover events, such as the one demonstrated by Tuk et al., could open a new pathway to the advancements on how we as humans could make better decisions. The result of better decision making would be greater general happiness through eradication of anxiety and depression that come as a result of self-control conflicts. Deeper research into other inhibitory responses, other than bladder pressure, within the field of behavioral psychology could be applicable to other behavioral subfields, like behavioral economics (Tuk et al., 2011). This could mean better financial decision-making and ultimately, better quality of life, through better impulse control. Gaining deeper insights into inhibitory spillovers could result in a deeper understanding and advancements of self-control conflict techniques. Proven harmful self-control techniques such as overindulgence and self-harm e.g., bruxism – clenching your jaws (which could lead to some serious dental issues) (The Bruxism Association, n.d.) or clenching your fists (which could lead to pain and stiffness) (Hung & Labroo, 2011; Meiwandi & Papadakis, 2019) could be a thing of the past. Still, there is much more to learn from inhibitory spillovers as it relates to better decision making and impulse control.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The Strength Model of Self-Control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x

Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019, August 13). [..Gov]. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Understanding-Sleep

Effects Of Bruxism. (n.d.). [..Org.uk]. The Bruxism Association. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from http://www.bruxism.org.uk/effects-of-bruxism.php

Elf, P., Gatersleben, B., & Christie, I. (2019). Facilitating Positive Spillover Effects: New Insights From a Mixed-Methods Approach Exploring Factors Enabling People to Live More Sustainable Lifestyles. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2699. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02699

Gray, J. A. (1981). A Critique of Eysenck’s Theory of Personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A Model for Personality (pp. 246–276). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-67783-0_8

Griffiths, D., & Tadic, S. D. (2008). Bladder control, urgency, and urge incontinence: Evidence from functional brain imaging. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 27(6), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20549

Hung, I. W., & Labroo, A. A. (2011). From firm muscles to firm willpower: Understanding the role of embodied cognition in self-regulation. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(6), 1046–1064. https://doi.org/10.1086/657240

Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of Control: Visceral Influences on Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272–292.

Mandal, A. Dr. (2019, April 9). Dopamine Functions [..Net]. News-Medical.Net. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Dopamine-Functions.aspx

Meiwandi, A., & Papadakis, M. (2019). The clenched fist syndrome: Case report of a clinical rarity of special interest for psychiatrists and hand surgeons. BMC Psychiatry, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2348-4

Merchán-Clavellino, A., Alameda-Bailén, J. R., Zayas García, A., & Guil, R. (2019). Mediating Effect of Trait Emotional Intelligence Between the Behavioral Activation System (BAS)/Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Positive and Negative Affect. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00424

Nilsson, A., Bergquist, M., & Schultz, P. (2016). Spillover effects in environmental behaviors, across time and context: A review and research agenda. Environmental Education Research, 23, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1250148

Scarpina, F., & Tagini, S. (2017). The Stroop Color and Word Test. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00557

Takemura, K. (2020). Behavioral Decision Theory. In K. Takemura, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.958

Tuk, M. A., Trampe, D., & Warlop, L. (2011). Inhibitory spillover: Increased urination urgency facilitates impulse control in unrelated domains. Psychological Science, 22(5), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611404901

Van den Bergh, B., Dewitte, S., & Warlop, L. (2008). Bikinis instigate generalized impatience in intertemporal choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/525505

Wansick, B., & Sobal, J. (2007). Mindless Eating: The 200 Daily Food Decisions We Overlook. Environment and Behavior, 39(1), 106–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506295573

Related Posts

The I.D.E.A. Initiative: Infectious Disease Educational Awareness

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreInvestigating the Quality of Healthcare in Rural Areas

Cover Image: A rural Metro ambulance in Memphis, Tennessee. Rural...

Read MoreA New Method to Track Parkinson’s Disease

Figure 1: 3D structure of alpha-synuclein protein. Mutations in alpha-synuclein...

Read MoreCollins Kariuki