This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023 Summer Program.

Source: Daniel Schludi

Abstract

Background: Covid-19 has been a growing public health issue in American households over the past several years, specifically the Hispanic pediatric population. In Illinois, Hispanic individuals accounted for about 25% of Covid-19 although they make up only 18.3% of the population. Only 12% of 5 to 11 years old who were vaccinated were of Hispanic descent. Although Covid-19 is no longer as large a public health concern, new strains derived from Covid-19 continue to put the Hispanic pediatric population at risk. Objectives: The Objective of our literature review is to investigate the Covid-19 virus while focusing on the social determinants of health, health implications, and interventions regarding these viruses and analyzing their impact on the Hispanic pediatric population. Methods: This literature review was conducted by synthesizing the findings from 77 scholarly sources about coronavirus disease and related topics. The data and findings were extracted from Google Scholar as well as national and international organizations such as the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO). Results: The populations at highest risk for Covid-19 were Hispanic children who tend to face greater risks due to their physical environment and socioeconomic status. Conclusion: Due to the relevant health disparities in Hispanic pediatric populations, implementing educational workshops on the prevention of infectious diseases may help alleviate public health issues in this community.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Infection, Healthcare, Hispanic, Children, Disadvantaged Population

Introduction

As of February 2024, Covid-19 has taken nearly 7 million lives worldwide. In the US alone, there have been 103,518,723 cases and 1,127,152 deaths. Given the magnitude of the pandemic and its effects, it is vital to educate the public on prevention methods to stay protected from Covid-19 and other future infectious illnesses. Covid-19 and other respiratory diseases significantly hurt the Hispanic community; within Illinois, the Hispanic community made up for 25% of deaths1. Unfortunately, this community has many underlying issues putting them at a higher risk for contracting the virus, especially children. 75% of children killed by the virus have been Hispanic, Black, and American Indian children, even though they only comprise 41 percent of the U.S. population2. Hispanic children experience worse illness and have a higher mortality rate than white children. Usually, these children live in multigenerational houses, which makes isolating difficult, and they are often exposed to the virus through family members who have high labor jobs that put them at greater risk of contracting the disease3. As of November. 7, 2021, Illinois provided 15,470 Covid-19 vaccines to 5- to 11-year-olds, of which only 12% were Hispanic when Hispanic individuals make up 18.3% of the population. The relatively low vaccination rates and the negative impacts on children result from lack of access to knowledge and healthcare providers in these Hispanic neighborhoods and often mistrust of the healthcare system4. Although Covid-19 is no longer as dangerous a public health threat as it was in 2020, new variants continue to send people to the hospital and take lives.

Methods

This research project was conducted using 77 government reports, peer reviewed journals, news articles and various other scholarly sources. The first component of the project, the National Literature Review, consisted of 50 scholarly sources that were found through Google Scholar. The team was able to gather data through government websites such as the CDC and Illinois’s state website. For the project’s second component, we reviewed news articles to understand the social impact of the virus while gathering data on patients and prevention strategies to overcome the virus. Finally, the project’s third component, the EBR literature review, consisted of 27 sources, though most of the data is gathered from the U.S Census Bureau. Additionally, the EBR review consists of sources that illustrate current interventions taking place within Illinois to support the Hispanic communities who are impacted by Covid 19.

In addition to the National Literature Review, review of news articles, and EBR literature review, we interviewed several individual stakeholders for a more personal perspective on the pandemic and the plight of the Hispanic community in particular. One of the stakeholders, Dr. Jennifer Piscano, Chief Director of Infectious Diseases from UChicago, provided us with further insight on infectious diseases and public safety from 2020 up until now. The team had interviewed Dr Piscano based on her research and her transition to chief director during the peak of the pandemic. A couple weeks later, we interviewed Dr. Moira McNulty who gave us insight on her previous interventions, and methods to build trust with the Hispanic community.

National Literature Review

Through the synthesis of 53 scholarly sources, our national literature review summarizes the epidemiology, social determinants of health, and health implications of the coronavirus nationwide and interventions for it.

Given the various social determinants of health that can affect an individual’s chance of contracting the virus, the paper focuses on race and ethnicity, age, and physical environment. By the peak of the pandemic, Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous hospitalizations, cases, and deaths were at an all-time high6. These individuals also face challenges such as low paying jobs which rarely allow quarantine time, putting them at a higher risk for contracting the virus7. With generally lower socioeconomic status, these groups are often uninsured and may struggle to pay for the hospitalizations and treatments. Among these groups with low socioeconomic status, cases among the elderly occur at higher rates. Physical environments also play a role in contracting the virus, since in the US boroughs like the Bronx, New York have higher proportions of case rates for Black individuals than boroughs like Manhattan. The Bronx has a higher number of Black and Hispanic individuals, leading to an increased number of deaths8.

Due to the physical environment, homeless people are also at higher risk as they live in crowded areas and are exposed to many individuals at the same time. They also tend to not receive nutritious meals, which weakens their immune systems and puts them at a higher risk of contracting Covid-19. Current interventions include school regulations on an organizational level and encouraging hygiene and social distancing at an individual level. Now that vaccines have been distributed, the case rates have slowed but further work to help minorities still needs to be implemented.

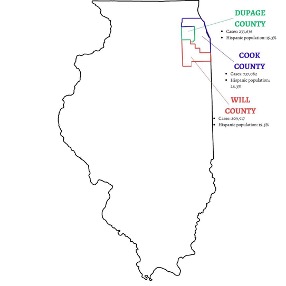

Figure 1. Illinois Counties with highest number of Hispanic cases and their percentages of Hispanic Population

Evidence Based Review

The Evidence Based review (EBR) focused on the gaps and disparities faced by Hispanic populations in Illinois during the coronavirus pandemic. Currently in Illinois, the northeastern region has had the most cases. Figure 1 shows the number of cases in each northeastern county and their respective percentages of Hispanic population.

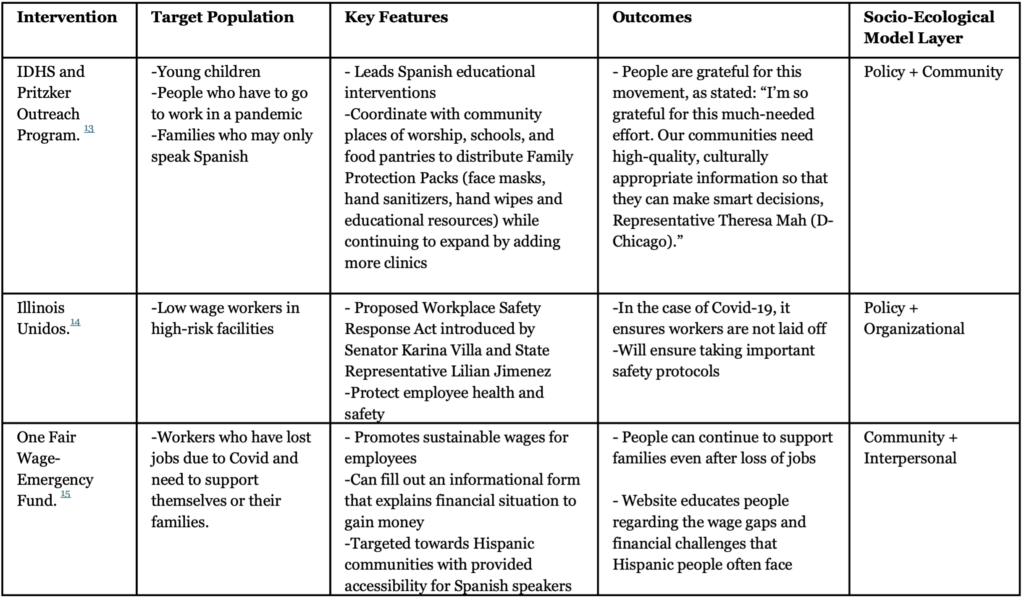

Although the Hispanic population in Illinois makes up just 11.7% of the whole population, they make up almost 60% of all cases in Illinois9. Various social determinants of health contributed to their elevated chances of contracting the virus. When the Governor of Illinois J.B. Pritzker announced the Stay-at-Home order, essential workers were exempt from it10. The Hispanic population was drastically affected since they are heavily employed in the “essential” jobs of production, material moving, and food preparation11. Thus, the population was left relatively unprotected from the virus, which put them and their families at a higher risk. Often in relation to their socioeconomic statuses, many Hispanic individuals refused to get tested for the virus in fear they would lose their jobs. Furthermore, 16% of Hispanic individuals lack healthcare coverage9,12. Currently, in Illinois, there are various organizations that work to support the Hispanic community in facing the aftereffects of the pandemic. Table 1 shows some of these organizations and what they do to help the Hispanic community.

Table 1. Interventions to support Hispanic communities in Illinois during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Stakeholder Perspectives

In addition to our literature review, we worked with stakeholders Dr. Jennifer Pisano, the chief of Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Alison Bartlett, an infectious diseases pediatric physician at UChicago. These physicians reside in the Chicago area and are associated with the UChicago medical system. Their expertise helped guide us in understanding the knowledge gaps that children have with regards to infection prevention at the hospital and provided insight into adapting our presentations for safety.

Plan of Action

Our intervention intends to target school-age children of ages six to 15 at the local Comer Children’s Hospital, as children are highly vulnerable to acquiring infectious diseases in hospital settings. This population is located in the Chicago area and will likely include a mix of various different ethnicities. We hope to empower at least 20 children to feel confident in protecting themselves and their community from infectious diseases in the future. We plan to start our intervention off with a quick introduction and a slideshow on infectious diseases. Then, we have two engaging games planned to show bacteria and transmission. Our first game is Virus Buster. The objective of this game is to illustrate how the chain of infection works and how infections can be spread. It operates as a freeze tag game where one person will be the host with the virus and tag other people with the virus. When a person gets tagged, they now carry the virus and are frozen, but other children will have to unfreeze them by using prevention methods previously learned including washing hands, wearing a mask, and getting vaccinated. Our second game is Glowing Guardians. The objective of this game is to create a compelling visual representation of prevention methods for infectious diseases. We plan to utilize glow in the dark bacteria kits to showcase bacterial growth before and after hand washing. We will demonstrate the proper hand washing technique and highlight the effectiveness of hand washing to reduce bacterial growth. Finally, we will end with the reflection of the games as well as do a Q&A to answer any unresolved questions. This strategy is likely to be effective: instead of being lecture-based and unengaging for children, we have incorporated various games to capture their attention and convey our message of infectious diseases control. Our timeline to implement this intervention is as follows:

August

- Plan our curriculum for Infectious Diseases Workshop

- Consult with Dr. Pisano to obtain feedback on our slides.

- Community outreach with a Go Fund Me to raise money for our materials.

September

- Test our curriculum out with children in our community.

- Recruit children from our community to participate in our workshop and give feedback.

- Edit our curriculum to ensure it is suitable for children at the hospital.

- Work out logistics of teaching at the hospital.

October

- Test out improved curriculum with different children in our community.

- Gain more feedback on our curriculum.

- Order supplies with fundraised money.

- Finalize dates for our workshop.

November

- Finish up last minute details for the workshop.

- Present the workshop.

- Analyze pre and post surveys to assess knowledge levels.

- Follow up with stakeholders for more feedback on our presentation.

December

- Send follow up information to the hospital.

- Refine our presentation with feedback from stakeholders and hospital children.

- Plan another workshop with different children at the same hospital.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the student intervention, we plan on having the students fill out a pre and post survey. The pre and post survey will estimate how much knowledge the students have gained over the course of the workshop. A key indicator that measures success include being knowledgeable about measures they can take to control the spread of infection. After we collect data from our pre and post surveys, we plan to analyze and determine a grade for each survey. Each question would be worth one point, and we would find the average of the change in points. After our pilot event, we plan to have check-ins with the Comer Hospital and stay in touch with the children by sharing goodie bags. Furthermore, we hope to get in touch with a local policy maker to review what policies could be implemented for infection prevention.

Strengths and Limitations

In order to create the most unique and appropriate infectious diseases workshop for children, we will be focusing on a hospital-based education initiative. This type of intersection will fill in any knowledge gaps children have about infection prevention in a hospital setting. The incorporation of various games will also deviate from a standard, traditional lecture while clearly conveying our message of prevention and control. To add value and a sense of belonging in this community, our mission is to invoke a well-rounded understanding of safety measures and precautions in the youth. These include but are not limited to the knowledge of prevalent diseases, the utmost safety, quality, and resources for low-income groups, as well as proper tips and methods. In addition, pre and post surveys will be implemented to evaluate the effectiveness of our student intervention.

Moreover, to combat the potential challenges that may arise in the process, all activities will follow proper provisions and safety at the hospital. Since it has also, to an extent, a long runtime, attention difficulty or hyperactivity are plausible for the students. To address these issues, our games will be designed to add excitement and fun so that there is less direct content coverage and more “show, don’t tell.” In other words, we aim for students to recognize the impact from this session themselves, rather than having it read aloud to them.

Discussion

Throughout history, infectious diseases have had profound impacts on societies. Respiratory illnesses tend to emerge and re-emerge at alarming rates. With the recent Covid-19 pandemic, the world has witnessed several disease outbreaks and epidemics related to this unwelcomed infectious agent, which has inflicted unparalleled challenges on health systems worldwide. The coronavirus pandemic outbreak significantly disrupted the United States economy, leading to substantial human losses and the closure of major economic sectors. It has created tremendous interference in people’s lives, stretched healthcare systems to their utmost capacities, and has led to a global economic decline — as of today, 7 million lives have been lost around the world.

Based on our previous findings, it is evident that on the public health front, the spread of the virus has exhibited clear trends among racial and ethnic groups, especially in densely populated urban communities. Disparities in the social determinants of health (i.e. income, healthcare access, education, housing) are interconnected and place certain racial and ethnic minority groups at higher susceptibility to contracting Covid-19, disproportionately affecting Hispanic populations, for example. Specifically, the Hispanic community in Illinois has many underlying factors which put them at a higher risk of contracting the virus, as evidenced by our literature reviews. These issues can weaken the immune system and restrict the body from effectively fighting the virus off, resulting in higher hospitalization rates and treatments. Our national analytics clearly testify to the racial disparities that are present in Illinois, where the pandemic exacerbates existing economic inequities that the socioecological model suggests.

Our Evidence-Based Research Paper also indicates the factors that put children in Illinois are at risk and we hope to use this information as a guide, in accordance with our prior knowledge of ethnic disparities. Our collaborative partnership with Dr. Jennifer Pisano, the chief of Infectious Diseases at UChicago, and Dr. Alison Bartlett, an infectious diseases pediatric physician, has aided our understanding of children’s knowledge gaps in infection prevention at the Comer Children’s Hospital, and helped us to develop effective interventions that maintained safety boundaries and precautions. We will work together to encourage awareness among Hispanic pediatric populations regarding infectious diseases by planning successful community interventions.

Our intervention intends to target school-age children at a local hospital because children are highly vulnerable to acquiring infectious diseases in hospital settings. This population is located in the Chicago area and will likely include many individuals of primarily Hispanic identity. To address infectious disease education in children, we will be focusing on a hospital and school-based education initiative. In partnership with Dr. Jennifer Pisano and the Infectious Diseases Team at UChicago, we hope to work with the Comer Children’s Hospital to safely teach admitted children how to stay safe from infectious diseases, especially at the hospital. By hosting an educational workshop there, we plan to raise awareness for infectious diseases and answer any questions that children may have about other infectious diseases after the pandemic, achieving our objectives and goals.

One possible barrier to this intervention is not being able to host an in person session due to safety. We plan to work with our stakeholders to see if we can send a STEM box and show them videos of our games and lesson plan virtually. In the end, our mission is to create a compelling visual representation of prevention methods to the marginalized youth.

Conclusion

Covid-19 has disproportionately affected the Hispanic community, especially children who live in multigenerational households and are unvaccinated. Despite the existing interventions set in place to help these individuals, more must be done to mitigate the public health issue. Through our intervention, we hope to expand education and techniques for the infectious diseases to Hispanic children in the Chicago area, so that they feel confident in protecting themselves and their families from infectious diseases. Moving forward, we hope to target our program in other areas nationwide with high rates of Covid-19 cases and vulnerable Hispanic communities.

References

- Acevedo, N. (2020). In Illinois, Latinxs have highest cases of coronavirus, and officials worry about a spike in deaths. NBC News https://www.nbcnews.com/news/Latinx/illinois-Latinxs-have-highest-cases-coronavirus-officials-worry-about-spike-n1202181.

- Wan, W. (2020). Coronavirus kills far more Hispanic and Black children than White youths, CDC study finds. The Washington Post.

- Mitropoulos, A. (2021). Children of color disproportionately impacted by severe Covid-19 and related illness, data reveals. ABC News https://abcnews.go.com/Health/children-color-disproportionately-impacted-Covid-19-data-reveals/story?id=76063845.

- Smylie, S. (2021). COVID vaccination rates low for Black and Latinx children in Illinois. Chalkbeat Chicago https://chicago.chalkbeat.org/2021/11/10/22775481/covid-vaccine-hesitancy-black-hispanic-children-illinois.

- [No title]. https://covid19.who.int/table.

- Diaz, A. A. & Celedón, J. C. (2021). Covid-19 vaccination: Helping the latinx community to come forward. EClinicalMedicine 35, 100860.

- Page, K. R. & Flores-Miller, A. (2021). Lessons We’ve Learned — Covid-19 and the Undocumented Latinx Community. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 5–7.

- Wang, R. et al. (2022). Artificial intelligence for prediction of Covid-19 progression using CT imaging and clinical data. Eur. Radiol. 32, 205–212.

- Northern Illinois Annual Conference. (2023). Covid-19 pandemic impacts Hispanic/Latinx community. Northern Illinois Annual Conference https://www.umcnic.org/news/Covid-19-pandemic-impacts-hispaniclatinx-community.

- Executive order. https://www.illinois.gov/government/executive-orders/executive-order.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Explore Census Data. https://data.census.gov/.

- Covid-19 reveals health and economic inequities among Latinxs. https://www.bcbsil.com/newsroom/category/community-health/Covid-19–Latinx-disparities.

- [No title]. https://www2.illinois.gov/IISNews/22436-Pritzker_Administration_Launches_Outreach_Campaign_to_Support_the_State%E2%80%99s_Latinx_and_Immigrant_Communities.pdf.

- Home. (2020). Illinois Unidos https://illinoisunidos.com/

- Home. One Fair Wage https://onefairwage.site/

Related Posts

The E.C.H.O. Initiative: Encouraging Cardiovascular Health Through Outreach

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreTo safeguard Africa’s topmost predators

From Nepal’s bengal tiger to Kenya’s big Lions, conservation of...

Read MoreThe Public Health Humanitarian Crisis in Ukraine

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreNeuroscience, Narrative, and Never-Ending Stories

Figure 1: A field of poppies. The myths of Persephone...

Read MoreThe Public Health Crisis of Alzheimer’s Disease in African American and Hispanic Populations

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst...

Read MoreThe COVID Brain

Cover Image: The Structure of the Coronavirus. (Source: Wikimedia Commons,...

Read MoreSarah Narula, Shaila Pochiraju, Kshithi Prasanna, Rayaan Shaik, Arman Kakkar