Figure 1: Comparison of smallpox (left) and cowpox (right) inoculations 16 days after administration.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The historical practice of inoculation was a major precursor to the development of vaccinations. Prior to the widespread use of inoculation in the 18th century, it had been recognized that some diseases don’t reinfect a person after recovery. Smallpox was one of the first diseases that was treated through inoculation methods. Inoculation originated in either India or China some time before 200 BC (Boylston, 2012). In many cases, inoculations were performed by buying a few scabs or pus from someone suffering from smallpox, and then puncturing the skin of an uninfected person with a needle which had been in contact with the virus (Boylston, 2012). However, inoculation was not without risks. The public was concerned that recipients of inoculation might develop smallpox and spread it to others. Additionally, there was concern about the transmission of other diseases, such as syphilis, which could also be introduced to the body during inoculation via bloodborne pathogens (Boylston, 2012).

Many physicians sought to remedy these concerns, one of whom was the famed Edward Jenner. The Scottish physician had heard tales that dairymaids were protected from smallpox naturally after having suffered from cowpox. Since the effects of cowpox were more mild than smallpox, Jenner decided to initiate one of the world’s first clinical trials – systematically inoculating people with cowpox to see if it could effectively confer resistance to smallpox infection. Jenner devised an alternative to variolation (inoculation with smallpox) where he controlled the transfer of pus from one person’s active cowpox lesion to another person’s arm (Stern, 2005). He concluded that the introduction of cowpox to one’s body not only protected against smallpox but also could be transmitted from one person to another(Bazin, 2011). Vaccination offered the public a less-harmful, and more efficient method of preventing smallpox.

Since Jenner’s smallpox vaccination, many developments have taken place to improve the safety, efficacy, and delivery of vaccines. The middle of the 20th century was an active time for vaccine research and development as methods for growing viruses in the laboratory led to rapid discoveries and innovations, including the creation of vaccines for polio (Duffy, 1990). This further led to researchers using vaccines to target other common childhood diseases such as measles, mumps, and rubella (Plotkin, 1999). Today, innovative techniques drive vaccine research, with recombinant DNA technology and new delivery techniques leading scientists in new directions (Alcock et al., 2010). At the same time, disease targets have expanded, and some vaccine research is beginning to focus on non-infectious conditions such as addiction and allergies. From Jenner’s trial to today, the practice of vaccination has saved countless lives – and especially in the coming months, it will save many more.

References

Alcock, R. ., Cottingham, M., Rollier, C., et al. (2010). Long-Term Thermostabilization of Live Poxviral and Adenoviral Vaccine Vectors at Supraphysiological Temperatures in Carbohydrate Glass. Sci. Transl. Med,. 2010; 2(19), 19ra12.

Bazin, Hervé. (2011). Vaccination: A History from Lady Montagu to Genetic Engineering. (Montrouge: J. Libbey Eurotext. , 2011)

Boylston, Arthur. (2012). “The origins of inoculation.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 105(,7), (2012): 309-13. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.12k044

Duffy, J. (1990). The sanitarians: a history of public health. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. , 1990.

Edsall, G. (1964) Smallpox Vaccination vs Inoculation. JAMAJournal of the American Medical Association, . 1964;190(7), :689–690. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070200125036

Plotkin, SA & , Orenstein, WA. (1999). Vaccines. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders Co. , 1999.

Related Posts

Looking into the Past for a Glimpse of the Future: Using Medieval Tonics as Modern Antibiotics

Figure 1: In the image above, one can see a...

Read MoreMedical Overtreatment in the United States: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions

This article was originally submitted to the Modern MD competition...

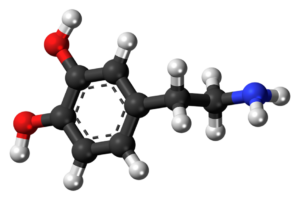

Read MoreLearned Control of Spontaneous Dopamine Impulses in Mice

Figure: Dopamine is the so-called “feel-good” neurotransmitter, involved in cognitive...

Read MoreSanah Handu

Comments are closed.