This article was originally submitted to the Modern MD competition hosted by the Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science (DUJS) and was recognized as an honorable mention.

Abstract

Healthcare practitioners have a responsibility to adhere to ethical guidelines during all medical procedures. But in certain cases, these guidelines are breached. Medical overtreatment is such a case. The phenomenon of overtreatment operates in discordance with the four main bioethical principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice/equity. The over-provision of medical treatment has peaked in recent years due to the combination of technological advancements, public beliefs, and financial incentives. From the patient’s perspective, the cost is high: physical iatrogenesis—injuries obtained through medical care— and excessive expense on medications and procedures that are unnecessary. To reduce the overuse of medical resources, solutions like reducing incentivized systems, amending the liability system, and enlightening medical students should be implemented. Most importantly, the healthcare system should explicitly stress the importance of granting patient autonomy through communication. This study examines how ethical issues underlie overtreatment in the United States an provides an instructive framework to examine causes, effects, and solutions of medical overtreatment.

Introduction

In the 21st century, as medical improvements spanning from novel drug development, to improved screening methods, to diagnostic testing have emerged, a novel ‘epidemic’ has steadily risen in prominence — overtreatment. Overtreatment refers to the prescription of unnecessary treatments and medications by physicians to patients with little evidence of benefit – or worse yet, prescribing medical interventions that inflict bodily harm (Carter & Barratt, 2017). As opportunities to use new technologies have increased, so have the numbers of therapeutics and medications. However, the public should recognize that use of additional medicines do not necessarily lead to increased physical health and psychological well-being; rather, increased drug use may impede good health. In the United States, one recent online survey sent to American Medical Association physicians revealed that the majority of those asked estimated 15 to 30% of their fellow doctors overtreated their patients (Lyu et al., 2017). Reported percentages of overtreatment in Madhya Pradesh, a rural city of India, were even higher – according to one study, 41.7% of sampled physicians prescribed unnecessary treatment to standardized patients (patients trained and rehearsed to enter doctors’ offices and demonstrate particular symptoms), signifying the relevance of the issue in both developed and developing regions (Das et al., 2012).

Overdiagnosis is often stated as the cause of overtreatment. Overdiagnosis refers to the (mis)diangosis of a medical condition that is, in fact, not harmful to an individual’s ordinary lifestyle (InformedHealth.org, 2017). Overtreatment follows early and unnecessary diagnoses, and complicates the ethical duties of physicians.

What are these ethical duties? The basic principles of medical ethics are beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and autonomy. Together they define the fundamental needs that doctors need to maintain as they provide care (Varkey, 2020). All four aspects are violated by overtreatment. One major challenge of medical treatment from an ethical standpoint is that not all members of the public, and even of the medical field, agree on what is improper. Whereas some may claim that certain procedures are morally right, others may claim them too harmful (or not helpful enough) and too costly to be justified. It is necessary to be cognizant of the viewpoints of all parties before rendering a verdict on what is proper and what it not. It is only after such an analysis that when we can arrive at a proposal to combat overtreatment ; one that reflects the spirit of Euripides, “Not too little, not too much: there safety lies.”

Medical Ethics and the Underlying Causes of Overtreatment

From a bioethical perspective, overtreatment has long been a major point of discussion. One could say that the most important parts of medical care are the physiological result of patient rehabilitation or the diagnosis of the true cause. In achieving these goals, the physician should act out of beneficence — the moral duty to provide positive outcomes to the best of one’s abilities (Varkey, 2020). Of equal importance is the creed of doing no harm, or non-maleficence. On top of these two standards, it is increasingly recognized that physicians ought to maximize patient autonomy. Autonomy, as defined in medical ethics, refers to the self-governance or self-control of patients in their responsibility of taking medications, receiving treatment, and receiving diagnostic tests (Varkey, 2020). In healthcare, autonomy is limited without knowledge. Without sufficient knowledge, patients hold misconceptions or may be subject to purposeful disinformation from physicians with financial pursuits in mind (Varkey, 2020). Thus, patient autonomy rests on the principles of justice and equity, which dictate that the public have broad and equal access to information and resources (Varkey, 2020).

Why is overtreatment so prevalent in the US medical system? One can start by asking doctors themselves. In 2017, an online survey was sent out to doctors from the American Medical Association, collecting opinions about the extent of the overutilization of medical resources and its possible causes (Lyu et al., 2017). The majority of respondents (84.7%) ascribed the reason for overtreatment to a fear of malpractice if treatment was to be found lacking, while 59.0% replied “patient pressure/request” as the cause (Lyu et al., 2017). Although only 2-3% of patients who claim to have received negligent care seek litigation, fears of medical claims are still very common among doctors, particularly since one lawsuit can profoundly damage their reputation and risk their license to practice medicine being stripped (Bell et al., 2012).

The liability system of the United States is managed primarily by state courts, rather than the federal government (Bal, 2008). Therefore, the decisions vary from state to state, but studies have found malpractice lawsuits to be relatively common in the United States in comparison to other Common Law countries (Ross, 1977). To be held accountable for an injury, the patient must prove that the fault was due to the negligence of the physician without their own intervention (Bal, 2008). If the physician is proved to be at fault, they need to provide monetary compensation to the patient, which includes recouping economic losses from the injury, the costs of future medical care, and the costs of non-economic adversities such as mental suffering or trauma (Bal, 2008). Regardless of the outcome, the preparation for jurisdiction trials itself takes substantial time, resources, and money (Bal, 2008). On average, the plaintiff and defending clinician spend more than $100,000 on the preparation of medical negligence lawsuits alone (Bal, 2008). Such preparation often includes hours of conversations with the attorney, interviews, reviews of records, and appraisal of legal conventions (Bal, 2008). Thus, there is undeniable anxiety that accompanies the cumbersome procedures of lawsuits, whether the physician was at fault or not. Another motivation for overtreatment may stem from the fear of harm; endangering a life due to undertreatment brings a hefty psychological cost for doctors who are passionate about the health and satisfaction of patients.

The remarkable percentage of physicians who stated “patient pressure/request” as their reason for overtreatment demonstrates the unfortunate and commonplace communication barriers which exist between patients and their caregivers. The public may assume that more tests and screenings lead to better care, which puts pressure on doctors to provide additional medications lest they risk dissatisfaction with their hospital (Lyu et al., 2017). The term “patient pressure/request” may actually illustrate the lack of communication and thus lack of patient autonomy. A survey reported that 89% of doctors thought “patient experience” was a critical factor of quality care and of significance, but only 16% affirmed that they ask patients their expectations (Rozenblum et al., 2011). These statistics determine the lack of patient self-governance, as doctors who do not acknowledge patient expectations are likely to give treatments that are not consistent with the patient’s preferences. Physicians need to acknowledge that valuing patient autonomy and communication is correlated to better patient experience and health outcomes, as well as fewer lawsuits and greater patient satisfaction (Chandra et al., 2018).

Overtreatment and Overdiagnosis: Benefits and Drawbacks

Medical radiation (from CT scans, X-rays, radiotherapy, etc.) is the largest man-made source of radiation today (World Health Organization, 2016). Notably, the United States recorded an average medical-induced radiation exposure five times the global average between 2009 and 2010 (World Health Organization, 2016). The country’s rapid technological advancements have led to numerous applications of radiation, from radiopharmaceutical treatments to medical imaging. Among medical imaging techniques, CT scans and nuclear imaging both use significant radiation doses (De Gonzalez, 2011).

Figure 1: Radiation Dose Chart which compares radiation exposure from Chest CT to other non-medical exposures, including the maximum yearly dose permitted for US radiation workers. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Randall Monroe)

Additional screenings are a major category of overdiagnosis and overtreatment and have the potential of both benefiting and injuring patients. For example, patients undergoing more screenings than the suggested number have a significantly greater chance of detecting early stages of cancer or pre-cancerous masses (Welch & Black, 2010). A report on the diagnosis of breast cancer from 15 years of follow-up on mammography screenings concluded that from the 477 cancers diagnosed by screenings, around 115 (16%) did not go on to reveal any symptoms or cause injuries – in other words, these cases were false positives (Welch & Black, 2010). This finding was even more dramatic when the diagnostic method was the chest x-ray ; approximately 32% of cancer diagnoses in one study were found to be false positive, causing no lasting harm to the patient over time (Welch & Black, 2010).

On the other hand, frequent screenings can also lead to radiation-induced harm. Considering digital mammographic screening for a population of 100,000 women – and knowing the amount of radiation required for a standard mammogram – scientists estimated that screenings are likely to induce 125 cases of radiation-induced breast cancer and 16 deaths (Miglioretti et al., 2016). The researchers claimed that in proportion to the number of averted deaths without screenings, the 16 deaths were not trivial, and thus efforts to diagnose patients do have significant downside (Miglioretti et al., 2016). Clinicians should acknowledge this fact and be open about all risks of harm to their patients.

The negative aftermath of overdiagnosis and overtreatment also manifests in the treatment of mental disorders. One study found retrospectively that 16.7% of child psychotherapists diagnosed patients with ADHD when case vignettes did not meet the official diagnosis criteria and concluded these results as proof of overdiagnosis (Merten et al., 2017). After being diagnosed with ADHD, these patients would receive psychiatric treatment, which may lead to additional diagnoses of psychological afflictions (Merten et al., 2017).

It should be noted that it is difficult to be sure that a psychological condition has been over-diagnosed (even in retrospect) because of the inherent complexity of psychological disorders. For example, you can’t perform a blood test or a biopsy to confirm that an individual does or does not have ADHD. Yet over-diagnosis is still imperative to acknowledge and attempt to reconcile with. Due to unnecessary psychotherapy or inappropriate medications, these patients are likely to experience psychological trauma and possibly develop new symptoms because of the clinician’s projections.

Clearly, in both cases – of cancer screening and diagnosis of psychological disorders – there are benefits and harms associated with additional screenings and medications; however, a procedure capable of inducing greater harm should not be exercised.

Economic Considerations

Overtreatment has dramatic economic as well as human consequences. A recent meta-analysis estimated that the total yearly waste (healthcare spending that is not considered beneficial) from the United States healthcare system equaled approximately between $760 billion to $935 billion, accounting for almost 25% of the total spending from the national healthcare industry (Shrank et al., 2019). Moreover, the particular category of “overtreatment and low-value care” was individually responsible for an estimated $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion, taking up approximately 1/7th of the total annual waste (Shrank et al., 2019).

What accounts for this waste? 71% of clinicians surveyed in the American Medical Association “believed that physicians were more likely to perform unnecessary procedures when they profit from them.” (Lyu et al., 2017). In some cases, overtreatment costs can be siphoned off by doctors, particularly in the private sector, as these financial benefits are incentivized (Frey, 2008). The private sector often has less robust regulations of cost-control, and prices in the private sector have been reported up to 50% higher than average hospital costs in the United States (Barber et al.). Thus, willingness to provide additional yet unnecessary care may heighten for private providers. For instance, in Switzerland, there was evidence of privately insured adults having the highest rates of surgical procedures (Frey, 2008). Correspondingly, fees for invasive procedures done by specialists in the private industry are high, acting as incentives to physicians that may trigger needless surgeries or medications (Frey, 2008). From the perspective of underprivileged patients, these economic windfalls seem unethical and exploitative of a group that is already under economic hardship (Jha et al., 2002). The job of a medical practitioner is to serve appropriate care, yet overtreatment and overdiagnosis allow them to secure a greater amount of money from the pockets of patients. If this phenomenon exists, the idea of a fair transaction between physicians and patients is lost.

Prospective Solutions

In order to solve ethical questions surrounding overtreatment, it is critical that faults in the medical system be addressed so that overtreatment is disincentivized and patients are able to receive the full range of medical necessary to make autonomous decisions about their health. Patient-physician relationships make up the key elements to an effective and consummate healthcare system (Vento et al., 2018). Unfortunately, this trust has been progressively weakened by lack of interaction time, lack of autonomy, and tension from liability concerns (Vento et al., 2018). It is crucial to improve patient-physician communication with jargon-free, extensive, and comprehensive consultations. Initiatives such as the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes Project can be of considerable assistance for physicians who wish to reach out to medical practitioners across the globe to access medical education and case studies through teleconferencing systems (Arora et al., 2007). Institutions can also find methods to reduce the incentives placed on commercial medications and treatments. By limiting fee-for-service arrangements (payment method where doctors receive fees for each service performed) and introducing bundled payment measures (reimbursements to physicians based on expected costs for different occasions of care), clinicians can receive capped payments and ensure equity of resource selection, while simultaneously preventing overtreatment and overdiagnosis (Axene, 2017; Noah & Feigenson, 2016).

Figure 2: Image outlining a doctor consulting with a patient, which elucidates the importance of physician-patient communication. (Source: Pxhere, rawpixel.com)

At the heart of these problem are issues with the structure and organizations governing the medical system at large. A primary concern is the ever-present fear of malpractice lawsuits. Unfortunately, policymakers in the United States have not experimented with many reforms and attempts to place caps on non-economic damage costs have shown little efficacy in decreasing physician’s perceived liability threats (Frakes & Gruber, 2018). Ultimately, exhorting medical practitioners to ignore the pressure of the law does not solve the issue (Frakes & Gruber, 2018).

To relieve physicians of undesirable lawsuits, preventing defensive medicine, the American judicial system may need to learn from strategies used beyond its borders for tackling liability affairs. In most of Europe, a judge takes the place of the jury, often meaning that medical payouts are smaller and cases are resolved faster (Goldberg, 2012). New Zealand possesses a medical board in which patients file their claims, making it difficult for patients to easily initiate frivolous lawsuits (Bismark & Paterson, 2006). Another potential systemic approach would be adjusting medical school curricula to emphasize patient involvement and discourage overtreatment (Burgess, 1989). The curricula should prioritize the importance of quality care that respects patient autonomy – and its lessons should unfold not only through lectures but also during intern and later residency training, where students can experience first-hand how senior doctors conduct themselves ethically and communicate appropriately with patients. (Burgess, 1989).

The public too should share responsibility for dealing with their diseases and symptoms. Today, technology has permitted access to inexhaustible information; it takes just a couple of clicks to find medical details and expertise data from online sources. The National Council on Bioethics in Human Research has also highlighted the importance of community participation in medical research and cooperation with physicians (Burgess, 1989). Whether it be consulting physicians or questioning reasons for diagnoses, the patient should do one’s utmost to achieve patient autonomy and choose what is best for their own body.

Conclusion

Medical overtreatment, whatever its intentions, clearly has a dramatic negative effect on the health and well-being of the American public. While it may come from a place of concern on behalf of the physician, overtreatment can be a financial burden to the patient, lead to physical risk, or reflect the commercial intentions of healthcare practitioners. It is also critical to recognize that physicians in the United States suffer greater repercussions for alleged malpractice, which further encourages overtreatment. In order to decrease this trend, there should be a reinforcement of patient-physician interaction, where both sides treat each other with respect and attentiveness, rather than maintaining a service and customer relationship. Among bioethical principles, autonomy should be valued in solutions to enable patients to choose the correct options and create an environment of trust.

It should be noted, however, that the data presented in this paper comes from studies conducted in various geographic regions and at different time periods, and therefore may not reflect the most recent data within the United States. Furthermore, the conclusions have been proposed based on examined statistics and may not apply to other countries in different circumstances and with distinct governmental policies. There are also limitations to the solutions proposed. The rectifications of the law and financial systems of medical institutions are not simple. The introduction and referral of a bill can take years, and similarly, the medical system is not going to change its structure easily (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2012). Hence, rather than concentrating on official transformations, more focus should be placed on an individual’s capability to expand knowledge of their medical condition and reorientation of education towards patient interaction and autonomy.

Transcending the faults in the medical system is a shared responsibility of patient and physician, the collective effort being the only mechanism that will ensure good health for all. With physicians’ dedicated supervision, patients’ informed decisions, and the public eye set on policy reforms that push for quality care, it may be possible to curb the ‘overtreatment epidemic’ plaguing the United States.

References

Arora, S., Geppert, C. M. A., Kalishman, S., Dion, D., Pullara, F., Bjeletich, B., Simpson, G., Alverson, D. C., Moore, L. B., Kuhl, D., & Scaletti, J. V. (2007). Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 82(2). https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f68

Axene, J. W. (2017, August 22). Axene Health Partners, LLC. Axene Health Partners, LLC. https://axenehp.com/paying-healthcare-providers-impact-provider-reimbursement-overall-cost-care-treatment-decisions/

Bal, B. S. (2008). An introduction to medical malpractice in the United States. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 467(2), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0636-2

Barber, S., Lorenzoni, L., & Ong, P. (2019). Price Setting and Price Regulation in Health Care Lessons for Advancing Universal Health Coverage. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/OECD-WHO-Price-Setting-Summary-Report.pdf

Bell, S. K., Smulowitz, P. B., Woodward, A. C., Mello, M. M., Duva, A. M., Boothman, R. C., & Sands, K. (2012). Disclosure, apology, and offer programs: Stakeholders’ views of barriers to and strategies for broad implementation. Milbank Quarterly, 90(4), 682–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00679.x

Bismark, M., & Paterson, R. (2006). No-fault compensation in New Zealand: Harmonizing injury compensation, provider accountability, and patient safety. Health Affairs, 25(1), 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.278

Burgess, M. M. (1989). Ethical and economic aspects of noncompliance and overtreatment. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 141(8), 777–780. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1451310/

Chandra, S., Mohammadnezhad, M., & Ward, P. (2018). Trust and communication in a doctor- patient relationship: A literature review. Journal of Healthcare Communications, 3(3). https://healthcare-communications.imedpub.com/trust-and-communication-in-a-doctorpatient-relationship-a-literature-review.php?aid=23072

Das, J., Holla, A., Das, V., Mohanan, M., Tabak, D., & Chan, B. (2012). In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Affairs, 31(12), 2774–2784. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1356

De Gonzalez, A. B. (2011). Estimates of the potential risk of radiation-related cancer from screening in the UK. Journal of Medical Screening, 18(4), 163–164. https://doi.org/10.1258/jms.2011.011073

Department for Professional Employees. (2016, August). The U.S. health care system: An international perspective. Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO. https://www.dpeaflcio.org/factsheets/the-us-health-care-system-an-international-perspective

Euripides. (1886). The medea of euripides. In Google Books. Macmillan & Company. https://www.google.co.id/books/edition/The_Medea_of_Euripides/UM8fAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

Frakes, M. D., & Gruber, J. (2018, July 23). Defensive medicine: Evidence from military immunity. Www.nber.org. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24846

Frey, B. (2008). Overtreatment in threshold and developed countries. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 93(3), 260–263. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.124479

Goldberg, R. (2012). Medical malpractice and compensation in the UK. Symposium on Medical Malpractice and Compensation in Global Perspective: Part II, 87(1),. https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3828&context=cklawreview

InformedHealth.org. (2017, April 20). What is overdiagnosis? Nih.gov; Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430655/

Lyu, H., Xu, T., Brotman, D., Mayer-Blackwell, B., Cooper, M., Daniel, M., Wick, E. C., Saini, V., Brownlee, S., & Makary, M. A. (2017). Overtreatment in the United States. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0181970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181970

Merten, E. C., Cwik, J. C., Margraf, J., & Schneider, S. (2017). Overdiagnosis of mental disorders in children and adolescents (in developed countries). Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0140-5

Miglioretti, D. L., Lange, J., van den Broek, J. J., Lee, C. I., van Ravesteyn, N. T., Ritley, D., Kerlikowske, K., Fenton, J. J., Melnikow, J., de Koning, H. J., & Hubbard, R. A. (2016). Radiation-induced breast cancer incidence and mortality from digital mammography screening. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 205. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-1241

National Human Genome Research Institute. (2012). How a bill becomes a law. Genome.gov. https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/policy-issues/How-Bill-Becomes-Law

Noah, B., & Feigenson, N. (2016). Avoiding overtreatment at the end of life: Physician-Patient communication and truly informed consent. https://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1326&context=facschol

Ross, S. (1977). Streamlining medical malpractice jury use: The approach used by common law countries. Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 1(1), 47. https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol1/iss1/4/

Rozenblum, R., Lisby, M., Hockey, P. M., Levtizion-Korach, O., Salzberg, C. A., Lipsitz, S., & Bates, D. W. (2011). Uncovering the blind spot of patient satisfaction: An international survey. BMJ Quality & Safety, 20(11), 959–965. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000306

Shrank, W. H., Rogstad, T. L., & Parekh, N. (2019). Waste in the US health care system. JAMA, 322(15). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.13978

Varkey, B. (2020). Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Medical Principles and Practice, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1159/000509119

Vento, S., Cainelli, F., & Vallone, A. (2018). Defensive medicine: It is time to finally slow down an epidemic. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 6(11), 406–409. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i11.406

Welch, H. G., & Black, W. C. (2010). Overdiagnosis in cancer. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 102(9), 605–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq099

World Health Organization. (2016). Communicating radiation risks in paediatric imaging (pp. 11–26). https://www.who.int/ionizing_radiation/pub_meet/chapter1.pdf

Related Posts

A Spoonful of (Modified) Sugar as an Antiviral Medicine

Figure 1: A negative stain transmission electron micrograph of Influenza...

Read MoreHow the Bystander Effect on Security Robots can Hamper Law Enforcement

BigDog robots being tested under the supervision of a Boston...

Read MoreWhy Young Investigators Should Consider Prehospital Care Research

Figure 1: The author (14 hours and 10 patients into...

Read MoreThe Growing Prevalence of Anxiety as a Public Health Issue

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy...

Read MoreNon-Violence: a Strategy

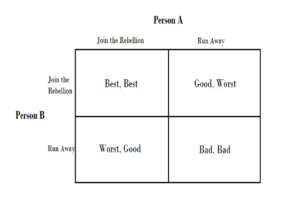

Figure: Assurance Game Payoffs. (Source: Author) It is puzzling that...

Read MoreA Novel Mental Health Literacy Education Program for Pre-Teens

Figure: A typical elementary school classroom in Japan (Cassidy, 2005). Source:...

Read MoreSeoyoon Lee