Figure: A person scrolling through news articles on their smartphone. FoMO has been largely studied in the context of social media and smartphone usage (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Japanexperterna.se).

Fear of missing out, or FoMO, is a feeling of apprehension that others are having positive or rewarding experiences where one is not present (Przybylski et al., 2013). FoMO has attracted much recent attention, especially in the context of social media and smartphone usage. In a study of 87 undergraduate students, Przybylski et al. (2013) found that FoMO was associated with Facebook engagement, distracted learning, and distracted driving. In other words, participants who reported experiencing more feelings of FoMO reported more engagement with Facebook during key times of the day (e.g., during meals, shortly after waking up and going to sleep). They were also more likely to use Facebook during class lectures, and paid more attention to their mobile phones while driving. In a more recent study of 834 adults in North America during the COVID-19 pandemic, Elhai et al. (2021) found that FoMO mediated the relationship between health anxiety (worry about one’s physical health) and both problematic smartphone usage (PSU; defined as excessive smartphone usage) and gaming disorder (GD; defined as excessive online and offline gaming activity). Thus, FoMO was an important variable that partially explained the relationship between health anxiety and both PSU and GD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although research has largely focused on the link between FoMO and both social media and smartphone usage, there is considerably less research looking at FoMO in different contexts.

To address this gap in knowledge, a group of researchers from the Sapienza University of Rome and the Catholic University of Sacred Heart in Italy ran a study of 26 adult volunteers where they sought to examine the neurobiological correlates of FoMO (Lai et al., 2016). After administering questionnaires asking about participants’ feelings of FoMO, engagement with social media, and attachment styles, they had participants undergo an experimental procedure where they viewed a series of images under electroencephalography (EEG). Each participant was placed in one of three conditions that determined the nature of the images shown to them, and these conditions were (a) social exclusion, where the images showed people who were cast aside from a group of others; (b) social inclusion, where the images showed people who were laughing and having fun as part of a group of others; and (c) neutral, where the images just showed everyday objects (Lai et al., 2016). After viewing the instructions for the task, participants underwent 30 total trials, where each trial included a small cross projected on the screen, followed by the image for the trial (Lai et al., 2016).

Analyses of the EEG and questionnaire data revealed an important main finding: Lai et al. (2016) found that participants who reported greater feelings of FoMO also experienced greater activation of the right middle temporal gyrus in response to the social inclusion condition images, compared to the social exclusion and neutral condition images. According to the researchers, this finding is consistent with previous studies that suggest the right middle temporal gyrus may have a role in processing social stimuli, such as differences in recognizing faces and facial features as well as in recognizing other people’s intentions (Brunet et al., 2000; Cecchini et al., 2013; Vartanian et al., 2013). For instance, in a study where 29 participants rated the attractiveness of a series of faces while scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Vartanian et al. (2013) found that higher ratings of attractiveness were associated with greater activation of the right middle temporal gyrus.

Although the main finding of this study is a promising step towards understanding the neurobiological correlates of FoMO, there are a few caveats that must also be considered. The researchers note that the Fear of Missing Out Scale (FoMOs), which was used to assess participants’ feelings of FoMO in the study, has not been validated in Italy where the study took place (Lai et al., 2016). Future studies can expand upon this limitation by examining participants from countries where the FoMOs has been validated, such as the United States (Przybylski et al., 2013). Other studies may also consider using different neurobiological techniques, such as fMRI, or consider variables closely associated with FoMO based on previous research such as problematic social media and smartphone usage. Looking forward, future research should continue to examine FoMO both in and out of the context of social media usage. Along with bolstering the scientific knowledge base surrounding FoMO, a more holistic approach to FoMO may also help improve researchers and practitioners developing and implementing interventions that may target FoMO, such as those aiming to curb problematic social media or smartphone usage.

References

Brunet, E., Sarfati, Y., Hardy-Baylé, M.-C., & Decety, J. (2000). A PET Investigation of the Attribution of Intentions with a Nonverbal Task. NeuroImage, 11(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.1999.0525

Cecchini, M., Aceto, P., Altavilla, D., Palumbo, L., & Lai, C. (2013). The role of the eyes in processing an intact face and its scrambled image: A dense array ERP and low-resolution electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA) study. Social Neuroscience, 8(4), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2013.797020

Elhai, J. D., McKay, D., Yang, H., Minaya, C., Montag, C., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2021). Health anxiety related to problematic smartphone use and gaming disorder severity during COVID-19: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.227

Lai, C., Altavilla, D., Ronconi, A., & Aceto, P. (2016). Fear of missing out (FOMO) is associated with activation of the right middle temporal gyrus during inclusion social cue. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.072

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Vartanian, O., Goel, V., Lam, E., Fisher, M., & Granic, J. (2013). Middle temporal gyrus encodes individual differences in perceived facial attractiveness. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031591

Related Posts

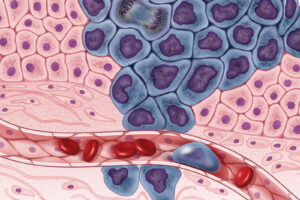

Single Cell RNA Sequencing Enhances Understanding of Tumor Genetic Diversity

Figure 1: Researchers have shown that tumor cells are a...

Read MoreThe Importance of Model Organisms

Many important discoveries in human biology that affect how we...

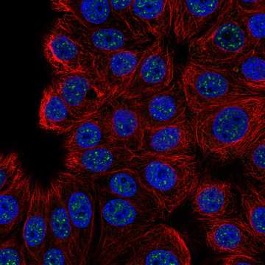

Read MoreProteins that Create “Speckles” in Cell Nuclei Discovered

Figure 1: A fluorescent microscopic image of the localization of...

Read MoreBacterial Treatment of Cancer

Abstract: Cancer treatment has long been an engaging field of...

Read MoreIntergenerational Trauma: How a history of pain brings biological costs

Source: Nicolas Raymond, CC BY 2.0 A few years ago,...

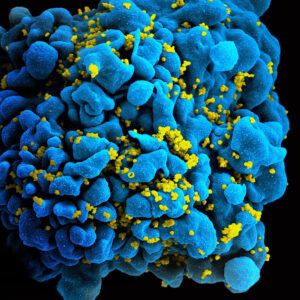

Read MoreHidden Cell-Based HIV Reservoirs Found via Sugar Signatures

Figure 1: SEM image of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)...

Read MoreVincent Lai