Figure 1: A field of poppies. The myths of Persephone and Helen of Troy suggest that the ancient Greeks were aware of the role the opium poppy plays in pain management

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Introduction:

At first glance, many people see science and storytelling as distinct and separate pursuits. A considerable portion of British authors from the Victorian era agreed — so much so that they aimed to supplant traditional fairy tales with educational materials, arguing that parents did their children a disservice in allowing them to waste time on fiction when the 19th century offered so many scientific revelations. Of this movement, children’s nonfiction author Priscilla Wakefield simply said, “Nonsense has given way to reason” (Keene, 2015, p. 10).

One fact this perspective fails to account for is that human storytelling is a result of evolution and is therefore, in a sense, driven by science. Storytelling is universal across human cultures, as are many narrative archetypes. As evidenced by ancient works of art including pottery, cave paintings, and carvings, storytelling predates writing (Zipes, 2012). As for how storytelling might increase evolutionary fitness in humans, one theory is that storytelling provides individuals with an opportunity to practice Theory of Mind, the psychological capacity to understand the perspectives and motivations of others. A strong Theory of Mind is essential for social interaction and would have enabled early humans to better predict each other’s behavior, benefiting individuals in an array of cooperative activities ranging from hunting to warfare (Williams, 2012). The use of narratives to structure how one views the world can lighten cognitive load, especially when it comes to processing embedded mental states (Willems et al., 2020). Van Duijn et al. (2015) describe embedded mental states as “A believes that B thinks that C intends (etc.)” (p. 148). In other words, embedded mental states allow an individual to consider how another person applies Theory of Mind to others, with the original individual utilizing their own Theory of Mind in the process. The more perspectives embedded, the more cognitively demanding comprehension becomes.

While embedded mental states can quickly become confusing if presented in isolated sentences, they are relatively easy for people to understand in the context of a story. For instance, Shakespeare’s Othello requires the audience to grasp that Iago wants Othello to believe that Desdemona cares for Cassio, but the presentation of this situation within a narrative allows it to be understood without undue cognitive strain (van Duijn et al., 2015). It can therefore be argued that narrative lightens one’s cognitive load, which might be evolutionarily advantageous because it can increase processing efficiency, allowing the brain to parse information with less energy. In other words, narrative is a built-in tool the human brain uses to understand the world. However, more than just evolution binds science to the tradition of storytelling. As this article will show through examples in Greek mythology, Indian mythology, and Victorian fairy tales, cultural narratives have a long and storied history of concealing morsels of scientific truth.

Greek Mythology:

The ties between mythology and science are evident from the etymology of “mythology” itself — “mythos” references traditional narrative, while “logos” refers to logic (Karakis, 2019). It is impossible to pinpoint the exact inspirations of legends created thousands of years ago, so modern historians and scientists settle instead for educated guesses based on a myth’s cultural, geographic, and technological context.

To begin, one needs only to look at the foundation — literally. The field of paleontology may provide key insights into some of Greek mythology’s greatest monsters. Of course, “paleontology” was a foreign concept to the Greeks. What did they make of fossils? Science correspondent Matt Kaplan hypothesized that these buried bones gave rise to mythical beasts like the Chimera and dragons and may even have inspired the legend of King Midas. According to legend, the Chimera was a fire-breathing lion with a goat head rising from its back and a snake for a tail. No single fossil could account for such a creature. Kaplan believes instead that multiple animals fell into a tar pit and were fossilized together, creating the appearance of one bizarre monster. Kaplan described the food chain at work, claiming that a goat, distressed at finding itself trapped in a tar pit, might attract a hungry lion, and the vultures coming to feed on the dead goat and lion could attract a bird-eating snake. As for the Chimera’s ability to breathe fire, Kaplan noted that Homer placed the Chimera in Lycia, where natural gas gradually leaks out, and the resulting blackened rocks and perpetual petroleum smell could have been thought to be supernatural in origin (Nissan, 2018). The existence of only one Chimera in Greek mythology lends credibility to Kaplan’s theory, since it is plausible that the tar pit scenario occurred once and became infamous.

Kaplan explained a potential origin of Crete’s Minotaur as well, focusing on the activity of local tectonic plates. Crete rests on the Aegean Block (a section of continental crust), and the Nubian Block (a section of oceanic crust) slides directly beneath the Aegean Block. This arrangement constitutes a subduction zone — a region of Earth’s crust where tectonic plates meet. The movement of the Nubian Block can displace the Aegean Block, resulting in abrupt uplift (at times over 30 feet) in Crete. Kaplan proposed that the resulting earthquakes could have given rise to the legend of the bellowing Minotaur lurking in an underground labyrinth. Kaplan even attempted to find scientific origins for the likes of Medusa and King Midas. Medusa’s horrible gaze was said to turn creatures to stone, and Kaplan theorized that this was how the Greeks explained the existence of fossils. Along the same lines, Kaplan pointed out that pyrite (fool’s gold) can accumulate within bone, giving a possible explanation for the myth of King Midas and his power to turn objects to gold (Nissan, 2018).

In addition to describing fearsome monsters, Greek mythology reflects some of the medicinal practices of ancient Greece. Helen of Troy supposedly used mandrake or opium to ease her anguish following her abduction and the start of the Trojan War. Persephone responded similarly to her abduction at the hands of Hades, using poppies to abate her emotional pain (Karakis, 2019). Today, opium-based drugs like morphine and other opioids remain key to alleviating pain. Interestingly, Greek mythology not only implies that the ancient Greeks understood the opium poppy’s role in pain management, but also indicates that the Greeks recognized that mental as well as physical conditions can require treatment (though they did not grasp that such mental conditions originated in the brain).

Hellebore is another medicine featured prominently in Greek mythology. In one legend, the Greek seer-healer Melampus healed the mad princesses of Argos (who were daughters of King Proetus and were therefore known as the Proetides) using hellebore. The concept of hellebore curing madness in mythology is not isolated to this story — similarly, Antikyreus is said to have cured Hercules with hellebore after Hera induced a fit of madness that led Hercules to murder his family. Olivieri et al. (2017) found that black hellebore in particular (Helleborus niger) is a psychoactive substance with calming, antipsychotic, and antidepressant capabilities that could have treated the madness of the Proetides and Hercules as described in legend, though there is insufficient evidence to justify the widespread use of black hellebore for such purposes today. While many myths of Greek antiquity seem ludicrous, there may be more truth to them than meets the eye.

Indian Mythology:

Like many of Kaplan’s hypotheses concerning Greek myths, the proposed origin of the Hindu god Vishnu is tied to paleontology. When geologist Hugh Falconer discovered a giant tortoise (Colossochelys atlas) fossil in northern India in the 19th century, he believed the existence of such a creature (or its remains) inspired the legend of Vishnu’s tortoise avatar. According to the story, Vishnu transformed into a tortoise and carried the world on his back. In a separate Hindu myth concerning the bird-god Garuda, a battle raged between an 80-mile-long tortoise and a 160-mile-long elephant. Considering the monstrous proportions of the actual giant tortoise (over seven feet tall with a shell diameter of over eighteen feet), it seems plausible that the tortoise’s fossil could have inspired both legends of monumental tortoises. Garuda, too, might have origins in a real creature. Chakrabarti and Sen (2016) hypothesized that Garuda himself was inspired by India’s gigantic crane (Ciconia gigantea). The war between Garuda and the Nagas (serpents) in both Hindu and Buddhist mythology may have been based on an observation of the natural enmity between birds of prey and snakes in nature, though Buddhist legends describe garudas as a mythical species, not a single deity (Nissan, 2018).

Like paleontology, astronomy was influential in Indian mythology. The Skanda Purana (a Hindu religious text) compared the Earth to a spinning top. The Indian mathematician-astronomer Aryabhata concluded from his work that the Earth spun, and the Skanda Purana is thought to reference Aryabhata’s findings — which, while correct, were not widely accepted — when it described the spinning of Earth (Kochhar, 2009).

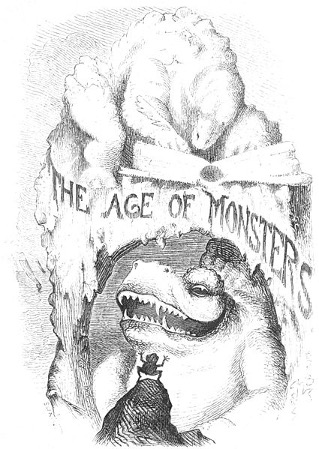

Figure 2: An illustration from John Cargill Brough’s The Fairy Tales of Science. Brough compared dinosaurs to more traditional fairy tale monsters

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Victorian Fairy Tales:

As discussed earlier, Queen Victoria’s Great Britain underwent something of a revolution when it came to the content of children’s entertainment. The result was a surge of science-based literature aimed at children, ranging from straightforward nonfiction to elaborate fantasies inspired by scientific concepts. As with Greek and Indian mythology, paleontology continued to play a major role in storytelling. John Cargill Brough’s The Fairy Tales of Science, for instance, sensationalized the newly discovered fossils of dinosaurs like the Plesiosaurus, Megalosaurus, and Cetiosaurus. Brough compared these extinct creatures to fairy tale monsters like dragons and griffins, penning detailed descriptions of fights between ferocious dinosaurs (Keene, 2015). However, this new brand of children’s literature was not produced by adults alone. Teenagers like Madalene and Louisa Pasley also contributed. The Pasley sisters published an illustrated entomology album, incorporating both actual and fictional adventures of theirs as they hunted for insects. This was part of a larger surge in scrapbooking among upper-middle-class women at the time, and such scrapbooks frequently included insect illustrations (Keene, 2015).

However, this scientific emphasis in storytelling did not mean that the fairies of traditional fairy tales disappeared. In Fairy Know-a-bit: A Nutshell of Knowledge, author Charlotte Maria Tucker also dove into the world of entomology, using an insect fairy to explain various types of insects to young readers. Lucy Rider Meyer also sought to imbue science with a touch of magic in her work. Instead of focusing on entomology, however, Meyer emphasized chemistry, creating a specific type of fairy for each element and using the fairies to demonstrate basic molecular behavior. For example, Meyer introduced the states of matter as descriptions of the fairies’ varying activity levels. Part of the reason for the focus on small objects such as insects and molecules was that, during the Victorian era, parlor microscopes became affordable for many families in Great Britain. This was likely a significant influence for “Down the Microscope and What Alice Found There,” which some University of Cambridge students published in Brighter Biochemistry (a satirical illustrated journal inspired by the process and politics of laboratory research). A bacterium called Pyo (short for Bacillus pyocyaneus) served as Alice’s guide as she explored a droplet of water at a microscopic level, diving into this strange new world in a manner imitating the plot of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Keene, 2015). “Down the Microscope and What Alice Found There” reflected the merging of scientific writing with children’s literature. To be clear, these scientific fairy tales did not entirely replace traditional stories with dragons, knights, and mermaids; the two storytelling approaches coexisted as society at large continued to debate which one most benefited children. However, many of the new Victorian-age fairy tales were undeniably scientific.

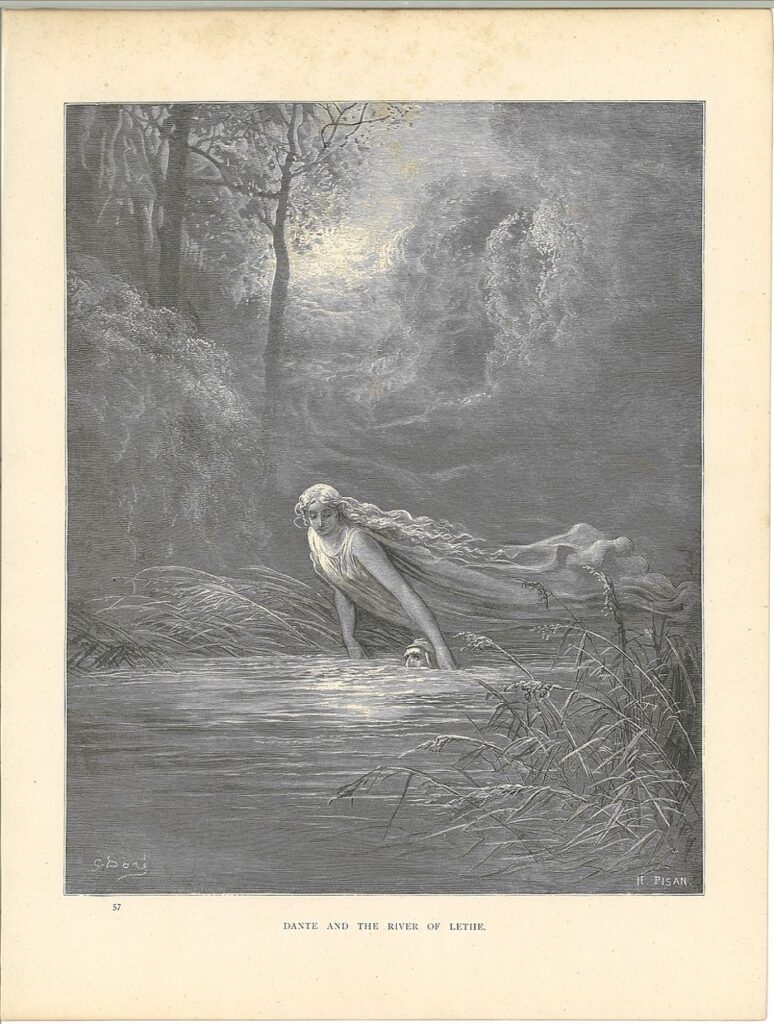

Figure 3: : Dante and the River Lethe. The Lethe supposedly erased the memories of the dead and is the origin of the modern word “lethargy”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Conclusion:

Though they have their differences, storytelling and science need not be divided. There is a rich history of literature embracing both disciplines. The relationship between science and storytelling can even be considered reciprocal. Just as scientific phenomena like Earth’s rotation and the discovery of fossils have influenced mythology, Ioannis Karakis (2019) noted that mythology has inspired many modern scientific terms like “lethargy” (after the river Lethe in the Greek underworld, which caused the dead to forget their lives), “panic” (after the Greek god Pan, who emitted a blood-curdling scream when woken from a nap), and “narcissism” (after Narcissus, who was cursed to fall in love with his own reflection). Similarly, the freshwater hydra, whose tentacles grow back when severed, borrowed its name from the Greek Hydra of legend, which grew two heads in the place of each one that was chopped off (Power & Rasko, 2008). Willems et al. (2020) even argued that narrative is a valuable tool that should be used more frequently in neuroscience research due to the key role narrative formation plays in human cognition.

In many storytelling traditions, such as that of ancient India, the transmission of mythology was oral (Kochhar, 2009). As a result, Indian storytelling retained a certain fluidity — different individuals told slightly different variations of traditional tales, and, over time, the tales changed as a result. This is one of the most fascinating aspects of human narratives — their remarkable capacity for change. Williams (2012) reflected that a person’s investment in any story relies on their personal past and memories. People are only able to understand narratives using experiences from their own lives. This article is a demonstration of that very concept. It is the availability of modern scientific findings that allows society to reexamine old stories with a more scientific lens. One could argue that the legends discussed in this article have no true end — like a language, they continue to evolve as long as they are in use.

References

Chakrabarti, P., & Sen, J. (2016). ‘The World Rests on the Back of a Tortoise’: Science and mythology in Indian history. Modern Asian Studies, 50(3), 808-840. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X15000207

Karakis, I. (2019). Neuroscience and Greek mythology. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 28(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2018.1522049

Keene, M. (2015). Science in wonderland: The scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

Kochhar, R. (2009). Scriptures, science and mythology: Astronomy in Indian cultures. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 5(S260), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743921311002146

Nissan, E. (2018). Monsters from Myth, and Quests for a Scientific Rationale, Or, a Science Journalist’s Take on Mythological Animals: An Exploration of Matt Kaplan’s The Science of Monsters, with a Foray into Aetiologies and Cultural Uses of Medusa. Amaltea, Journal of Myth Criticism, 10, 103–126. https://doi.org/10.5209/AMAL.58836

Olivieri, M. F., Marzari, F., Kesel, A. J., Bonalume, L., & Saettini, F. (2017). Pharmacology and psychiatry at the origins of Greek medicine: The myth of Melampus and the madness of the Proetides. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 26(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2016.1211901

Power, C., & Rasko, J. E.J. (2008). Whither Prometheus’ Liver? Greek Myth and the Science of Regeneration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(6), 421–426. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00009

van Duijn, M. J., Sluiter, I., & Verhagen, A. (2015). When narrative takes over: The representation of embedded mindstates in Shakespeare’s Othello. Language and Literature, 24(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947015572274

Willems, R. M., Nastase, S. A., & Milivojevic, B. (2020). Narratives for Neuroscience. Trends in Neurosciences (Regular Ed.), 43(5), 271–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.03.003

Williams, D. (2012). The trickster brain: Neuroscience, evolution, and narrative. The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

Zipes, J. (2012). The irresistible fairy tale: The cultural and social history of a genre. Princeton University Press.

Related Posts

Trust: The Essence of Good Policy Implementation

Figure 1 President Tsai Ing-wen inspects the Central Epidemic Command...

Read MoreThere’s NO Telling What Nitric Oxide Might Bring to Alzheimer’s Disease Research

Figure 1: As Alzheimer’s disease research begins to shift away...

Read MoreCaroline Conway