Figure 1 President Tsai Ing-wen inspects the Central Epidemic Command Center on April 2, 2020 (Source: Flickr, 總統府)

(A previous version of this article that describes the situation in the pre-Omicron wave can be found here)

Recently, an article in The Lancet medical journal article measured the biological, economic, demographic, and socio-political correlates of COVID-19 infection rates in different countries. The study found that government trust (as opposed to individual policies like lockdowns) were associated with statistically significantly lower infection rates (Bollyky et al., 2022). Why might trust be so important?

While it is generally thought that the success of a policy determines its legitimacy among voters in a democracy, trust plays an important mediating role. In policies for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens’ rights and policy success are in fact traded off: successful policies might require extensive monitoring of citizens, which violates people’s privacy and freedom. Generally, countries (such as the UK) that intended to give citizens freedom and uphold their privacy ended up failing to control the pandemic, having the worst death toll among all European countries (Farr, 2020; McTague, 2020). On the other hand, countries (such as Taiwan) that enforced successful policies have sacrificed citizens’ rights by extensive centralization and privacy intrusions (Farr & Gao, 2020). Yet citizens still complied without any strong dissent. How was this possible? Transparency and trust eased citizens’ fears and enabled Taiwan to secure people’s cooperation despite intrusion into their privacy. This cooperation helped the country achieve better health outcomes, with minimal compromise of freedom and privacy, at least as perceived by its citizens.

To control COVID-19, the UK and Taiwan implemented a variety of tools that ultimately imposed restrictions on people; their success varied based on the extent to which people’s privacy and freedom were curtailed. Taiwan, having experienced the SARS scare in 2003, was quick to institute a streamlined quarantine procedure for all foreign travelers and ramp up mass testing (Farr & Gao, 2020). Even within the country, people were extensively monitored through mobile apps, and masks were enforced in all public places (Farr & Gao, 2020). Every building tested the temperature of each entering person (Farr & Gao, 2020). As a result, as of January 27th, 2021, Taiwan has had only a total of 7 COVID-induced deaths (Taiwan COVID – Coronavirus Statistics – Worldometer, n.d.).

The UK’s COVID policies brought different results, however. The UK imposed a lockdown beginning late March, already 1–2 weeks late in terms of being able to save thousands of lives (Farr, 2020; “U.K. Delay Imposing Lockdown Cost Thousands of Lives, Report Says,” 2021). Mass testing replaced targeted testing only on 28th May—almost four months after the first COVID case was found in the country (Farr, 2020; Triggle, 2021). Also, the UK’s contact tracing system was initially limited (possibly to protect privacy) (Farr, 2020). In stark contrast to Taiwan, the UK suffered more than 100,000 deaths from 3.6 million COVID cases by January 2021 (United Kingdom COVID – Coronavirus Statistics – Worldometer, n.d.).

While Taiwan efficiently tapped population health data, the UK authorities, to safeguard privacy, lagged in getting the essential information to curb the pandemic. The UK National Health Service (NHS) created a centralized database for health records only in late March (Gould et al., 2020; Shead, 2020). From the database’s description, we can see that the citizen’s privacy is highly prioritized by the authorities — there is an entire section dedicated to addressing privacy concerns (Gould et al., 2020; NHS England » NHS COVID-19 Data Store, n.d.). On the other hand, Taiwan already had a centralized database that had everyone’s health records tied to their name long before the pandemic started (Farr & Gao, 2020). Doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals could easily access these details, including the individual’s travel history (Farr & Gao, 2020). Also, smartphone apps tracked people’s movements accurately and urgently alerted individuals who could have possibly been exposed to the virus (Farr & Gao, 2020). Although some people are concerned about the availability of such real-time data to the authorities, they trust the government to handle the data responsibly (Farr & Gao, 2020). This is what makes the difference between COVID management and mismanagement — trust.

Why did the UK’s policies inculcate distrust, despite the country’s attempt to protect freedom and privacy even at the cost of COVID mismanagement? First, political leaders were ambiguous in their messages to citizens (Farr, 2020). In the first few months of the pandemic, there was confusion about whether or not it was mandatory to wear masks or avoid travel and the like. This made local, individual decision-making difficult as people did not know whether they had to be masked on a bus, or whether they could hold small get-togethers. Moreover, leaders did not consistently follow their own policies: several of them were caught disobeying the lockdown orders for reasons like meeting a girlfriend.

UK’s policies during the recent Omicron wave were no different. There were a lot of speculations on when the COVID restrictions would end, and how they would ease out. The UK began discussing the easing of restrictions even as Europe was grappling with a heightened wave of viral spread (Ellyatt, 2022b). Moreover, it was recently discovered that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s cabinet held ‘industrial scale’ parties during the COVID lockdowns and restrictions (Ellyatt, 2022a). None of these contributed to greater trust in the government. As the Omicron wave tapers down in the UK, the country has already reported a record of 18.5 million cumulative cases and 160,000 deaths throughout the entire pandemic (“Covid-19 in the UK,” 2022). In stark contrast, Taiwan had only around 1800 cases in the past month, and only 1 Omicron-related death as of 19th February 2022 (Taiwan – COVID-19 Overview – Johns Hopkins, n.d.).

How was Taiwan able to repeatedly defeat the pandemic when most other countries struggled to do so? Particularly, what enabled the authorities to secure the trust of citizens — so much so that they were willing to compromise freedom and privacy? Taiwan elaborately laid out plans that worked, not only to ensure compliance, but also to increase the trust in the government. Farr and Gao describe the conditions: first, the social norms of mask-wearing and adhering to community health safety guidelines were in place ever since the SARS scare in 2003 (2020). The consequences of nonconformity were severe — violators would see their unmasked face all over social media should they be caught not wearing a mask in public. This opportunity for peers to punish defectors through social sanctions, coupled with the extensive governmental framework of rules, gave citizens the assurance that everyone in the country would follow the guidelines, in which case it was in their best interest to follow all the guidelines as well. Furthermore, leaders actually practiced what they preached; everyone in Taiwan followed the rules, from political leaders to ordinary citizens. Interestingly, while other countries faced a problem with citizens hoarding personal protection kits, Taiwan prevented this harmful information cascade in an efficient manner (an information cascade happens when people make a decision based on what they observe others doing over their own knowledge – so if people see many others suddenly rushing to buy PPE kits, they are likely to start hoarding PPE kits). The country’s mask inventory system gave citizens real-time data on the stock of masks in different locations, enabling them to pre-order masks and efficiently procure them from places that had enough stock.

The effectiveness of trust is best exemplified in the case of two more controversial parts of Taiwan’s strategy— a top-down approach in management and extensive monitoring — both of which still secured enthusiastic local compliance. Taiwan relied on a top-down approach through centralized planning: the strategy, as well as the data that was required to implement the strategy (the centralized health database), were entirely decided by the central government (Farr & Gao, 2020). Local officials played almost no role in dictating this policy. Additionally, Taiwan continued to extensively monitor its citizens even in the presence of strong social norms. The authorities imposed heavy fines on unmasked individuals and made multiple (online) visits in a day to people under quarantine (Farr & Gao, 2020). Decision-making and monitoring of this sort might otherwise crowd out civic virtue and decrease citizen compliance. But in the case of Taiwan, it did not.

These examples point to the power of trust: it can secure compliance even where it is otherwise limited. To prevent the failure of trust, the authorities took small but important steps. For example, quarantined people were repeatedly thanked for doing their duty as Taiwanese citizens (Farr & Gao, 2020). In exceptional circumstances like a global pandemic, states often have to rely more on laws than norms, which decreases the intrinsic motivation to comply. But messages like this essentially convert the law to a norm: following the law of staying in quarantine is the correct thing to do because the individual is upholding the norm of being a good citizen. Through repeated communication (daily briefings), the authorities made sure to mention that they trust locals (Farr & Gao, 2020). The locals reciprocated by trusting the authorities back. This trust was powerful enough to control the pandemic.

One may think that it is not trust, but rather that Taiwanese citizens are used to top-down and heavy-handed government control, while the UK has a greater citizen presence in governmental decisions. The democracy index measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture, prepared by the Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU, does not support this argument—EIU ranks Taiwan 8th in the world, higher than the UK, 18th (Averre, 2022; Hale, 2022)

Citizens’ trust in the Taiwanese government not only prevented the lack of social compliance seen elsewhere, but also eased fears about the compromise of privacy, which could have fomented strong dissent. The Taiwanese government upheld people’s trust by implementing policies that worked extremely well. Meanwhile, the UK sought to maintain its citizens’ privacy and freedom, but the resulting failure to do so affected everyone heavily. Truly, trust improves outcomes for all.

References

Averre, D. (2022, February 10). US and UK slip down global democracy rankings as Afghanistan becomes least democratic country | Daily Mail Online. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10498859/US-UK-slip-global-democracy-rankings-Afghanistan-democratic-country.html

Bollyky, T. J., Hulland, E. N., Barber, R. M., Collins, J. K., Kiernan, S., Moses, M., Pigott, D. M., Jr, R. C. R., Sorensen, R. J. D., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Allorant, A., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B., Carter, A., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., … Dieleman, J. L. (2022). Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: An exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. The Lancet, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6

Covid-19 in the UK: How many coronavirus cases are there in my area? (2022, February 18). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51768274

Ellyatt, H. (2022a, January 17). UK’s Boris Johnson in leadership crisis, accused of lying about “industrial scale partying” during Covid lockdowns. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/17/uks-boris-johnson-clings-to-power-as-partygate-scandal-rumbles-on.html

Ellyatt, H. (2022b, January 19). England looks to ease Covid rules while Europe is engulfed by omicron. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/19/england-looks-to-ease-covid-rules-while-europe-is-engulfed-by-omicron.html

Farr, C. (2020, July 16). The UK did some things right to fight the coronavirus, but it locked down too late. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/16/how-the-uk-fought-the-coronavirus.html

Farr, C., & Gao, M. (2020, July 15). How Taiwan beat the coronavirus. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/15/how-taiwan-beat-the-coronavirus.html

Gould, M., Joshi, I., & Tang, M. (2020, March 28). The power of data in a pandemic—Technology in the NHS. https://healthtech.blog.gov.uk/2020/03/28/the-power-of-data-in-a-pandemic/

Hale, E. (2022, February 11). Taiwan Ranks Among Top 10 Democracies in Annual Index. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/taiwan-ranks-among-top-10-democracies-in-annual-index-/6438806.html

McTague, T. (2020, August 12). Why Britain Failed Its Coronavirus Test. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/08/why-britain-failed-coronavirus-pandemic/615166/

NHS England » NHS COVID-19 Data Store. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2022, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/contact-us/privacy-notice/how-we-use-your-information/covid-19-response/nhs-covid-19-data-store/

Taiwan COVID – Coronavirus Statistics—Worldometer. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2021, from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/taiwan/

Taiwan—COVID-19 Overview—Johns Hopkins. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/taiwan

Triggle, N. (2021, October 12). Covid: UK’s early response worst public health failure ever, MPs say. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-58876089

U.K. delay imposing lockdown cost thousands of lives, report says. (2021, October 12). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/covid-lockdown-delay-cost-thousands-lives-uk-report-says-rcna2886

United Kingdom COVID – Coronavirus Statistics—Worldometer. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2021, from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/uk/

Related Posts

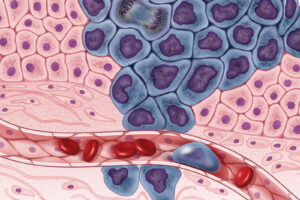

Rethinking ‘Junk’ DNA: The Vital Role DNA Repeats Play in Cancer and Aging

Figure: The image above, created by the National Institutes of...

Read MoreCranial Cartography: A New Method for Visualizing Blood Vessels and Stem Cells in the Skull

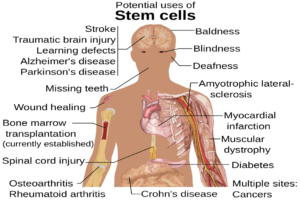

The diagram above displays the many potential uses of stem...

Read MoreLike Owls, These Tiny Desert Dinosaurs Hunted in the Dark

Figure 1: Animated drawing of the extinct theropod Shuvuuia Source:...

Read MoreSingle Cell RNA Sequencing Enhances Understanding of Tumor Genetic Diversity

Figure 1: Researchers have shown that tumor cells are a...

Read MoreThe Future of Wearable Devices

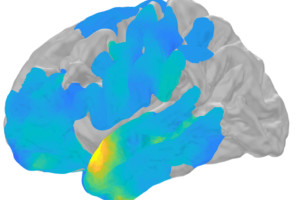

Figure: The colored sections of the brain represent the different...

Read MoreLearned Control of Spontaneous Dopamine Impulses in Mice

Figure: Dopamine is the so-called “feel-good” neurotransmitter, involved in cognitive...

Read MoreAnusha Kallapur