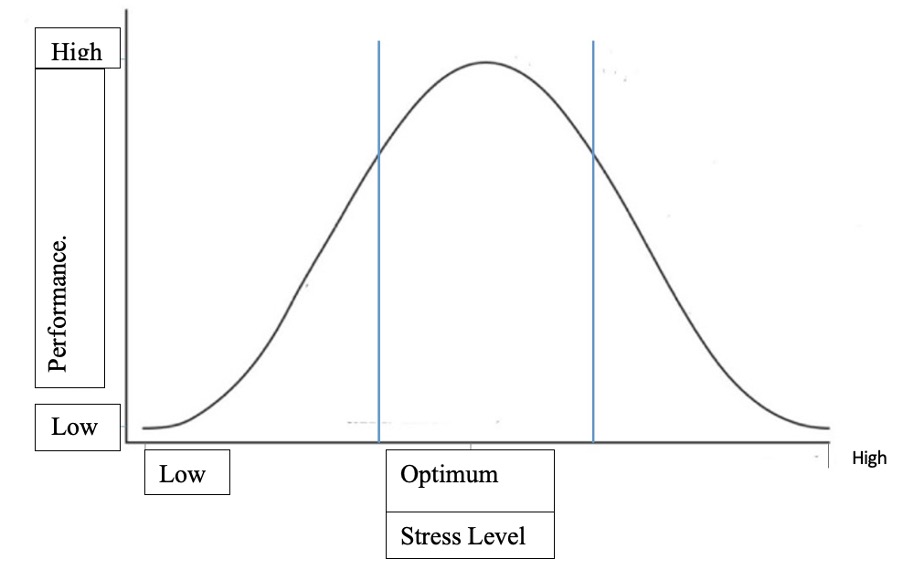

Figure 1: This graph compares stress level with performance at any job within the workplace

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The experience of emotions, which can elicit different kinds of stress, is an integral part of our lives. There is no clear-cut definition of stress but many professionals in the field of psychological science tend to classify stress according to its causative agents called stressors (Ursin & Eriksen, 2004). The effects of stress on human performance and behavior are immense, and more often than not, stress influences the quality of an individual’s daily work (Lench et al., 2011).The great question, then, lies in ascertaining the actual relationship between stress and performance; that is, whether the relationship is linear: as stress goes up performance does to an equal degree; inverse: as stress goes up performance goes down; or quadratic: as stress goes up performance rises even more dramatically. Many researchers have been trying to answer this question, and it may come as a surprise that a key answer has come from Japanese dancing mice.

In their classic 1908 paper published in the Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, Robert M. Yerkes and John D. Dodson endeavored to empirically investigate “The Relation of Strength of Stimulus to Rapidity of Habit-Formation.” That is, they sought to determine the relationship between different levels of cognitive arousal (roughly speaking, levels of stress) and performance using Japanese dancing Mice (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). In the experiment, which they dubbed “white-black visual discrimination habit,” they designed a wooden box with two electric chambers coated black and white to help determine habit formation among the dancing mice. The dancing mice were given a choice of either entering the white or black electric box. If the mice entered the black box, they would receive varying jolts of electric shock. If they entered the white box, they would not receive any electrical shock. Yerkes and Dodson went on to vary the brightness levels in the electrical boxes by the use of a screen that excluded a measurable amount of light, and again tested the choice of the dancing mice (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908).

Yerkes and Dodson concluded that the swiftness of habit-formation and the conditions of discrimination (the different brightness levels and colors of the boxes) were closely related. When the difference in brightness of the boxes was minimal, habit-formation became difficult and vice versa. This was also the case with the electrical stimulus. When the applied voltage was high, habit-formation came with ease. The opposite was true when voltage was low. When the conditions of discrimination were set at moderate levels, the rapidity of learning first increased with increasing amounts of stimuli up to a certain point and thereafter decreased with further increments of stimulation.

These results can be summed up in two versions of the famous Yerkes-Dodson law. For one, individual performance tends to improve with increasing cognitive arousal up to a certain point, but beyond that point, performance decreases. Second, the difficulty of tasks exhibits an inverse relationship with the degree of stimulation. Difficult tasks are more easily mastered in the presence of weak stimulation or low stress levels, while easy tasks are more easily mastered in conditions of strong stimulation or moderately high stress levels (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908).

This experiment, despite the fact that it was conducted on mice, has a tremendous impact on the scope of human cognition (Hogan, 2013). It raises the following questions: Emotionally, how should we handle different tasks? And what constitutes good or bad stress?

References

Gwyer, P. (2017). Applying the Yerkes-Dodson Law to Understanding Positive or Negative Emotions. Juniper Publishers, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.19080/GJIDD.2017.03.555606

Hogan, C. (2013). Chronic Stress. Australian Family Physician, 42(8). https://www.mcgill.ca/familymed/files/familymed/chronic_stress.pdf

Lench, H. C., Flores, S. A., & Bench, S. W. (2011). Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: A meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychological Bulletin, 137(5), 834–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024244

Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2004). The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00091-X

Yerkes, R., & Dodson, J. (1908). The Relation Of Strength Of Stimulus To Rapidity Of Habit-Formation. Classics in the History of Psychology. http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Yerkes/Law/

Related Posts

The E.C.H.O. Initiative: Encouraging Cardiovascular Health Through Outreach

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreGender Differences in Health and Medicine and the Importance of Gender-Specific Medicine in Healthcare Policy

This article was originally submitted to the Modern MD competition...

Read MoreRecent Study Conducted by Duke University Researchers Reveals Critical Limitation of fMRI Measurements

Figure 1: fMRI is used to display differences in basal...

Read MoreCollins Kariuki