Figure 1: While healthcare inequity is certainly an issue while prisoners are imprisoned, there are added concerns regarding the health conditions that develop or are exacerbated following their release

Source: Pixabay

For those incarcerated, the prison healthcare system severely impacts their quality of life and lifespan. Several studies have linked incarceration to poor health conditions, inadequate treatment, and the exacerbation of underlying health issues (Ginn, 2012). Despite calls for reform, funding to address these issues has been infrequent (Beckett et al., 2016).

In addition to these health concerns within prison, there is an added concern regarding rehabilitation following jail time. The medical problems, both mental and physical, of imprisoned individuals follow them after their release. No longer under the jurisdiction of the state, they left to contend with these illnesses from a social, financial, and mental health challenges – often without a much needed support network. This has measurable consequences in the mortality of patients that are released from prison (Cox, 2018).

There have been numerous studies outside of the US that have shed light on re-entry and the associated challenges – as well as the high mortality rate of prisoners following their release (Cox, 2018; Fairbanks, 2014; Wildeman et al., 2016). Such data, however, was not available in the US until a 2003 Washington study that followed prisoners released from correctional facilities between 1999 and 2003 (Binswanger et al., 2007). Increased vulnerability to drug use, death from violence, unintentional injury, and lapses in the treatment of chronic illnesses were all taken into account in order to shed light on what preemptive measures may be taken prior to reentry and during this transition to improve the health outcomes of former prisoners.

The Washington study followed some 30,000 inmates who were released from prison with an average length of incarceration of 23 years. Researchers found that 443 inmates died within one year of release. Looking specifically at the first two weeks, the mortality rate was 2,589 per 100,000. In essence, this meant that the death rate among ex-inmates was about 13 times higher than Washington State’s general death rate. Looking at the first week, we see an even more startling metric – a mortality rate of 3,661 per 100,000 people, about 18 times higher than the general mortality rate (Binswanger et al., 2007).

Analysis of the cause of death is critical to understanding the startling mortality rates. The primary cause of death among respondents within the two-week frame (out of 38 deaths total) was drug overdose, accounting for nearly one quarter of the deceased. The second leading cause of death was cardiovascular disease, and the third was homicide. Deaths from overdose, homicide, and suicide were more common among younger populations, while death from heart disease was more prevalent among older populations. Looking beyond just the first two weeks of life after prison, Biswanger et al. reported that within this study, there is a 3.5 times higher chance that inmates die versus normal Washington residents (Binswanger et al., 2007).

These numbers are staggering. It leads one to question what specifically could be responsible. Biswanger et al. suggest that structural inequity in education within prisons, care for mental illness within correctional facilities, and psychological stress due to re-entry without adequate support could have contributed to the rise of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and high rates of suicide. Moreover, for traditional recreational drug users, drug withdrawal during incarceration could have had profound impacts on their physiological tolerance for the drug, hence leading to an increased risk of overdose when they restart drug use after they are released from prison (Binswanger et al., 2007). The former issue has the possibility to be solved through additional support counseling services offered to released convicts and education through parole officers, while the latter can be potentially solved through additional education during incarceration.

In addition to the aforementioned support and education services, other interventions that have been proposed include halfway houses, work-release programs, drug-treatment programs, and preventative care to modify cardiac risk factors (Schoenfield, 2016). Finally, taking into account the disproportionate rate of incarceration for African American and Hispanic men, solving these shortcomings in the prison system within Washington state has the potential to decrease broader racial disparities in health as well.

References

Beckett, K,. Reosti, A., & Knapus, E. (2016). The End of an Era? Understanding the Contradictions of Criminal Justice Reform. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 664, 238–259.

Binswanger, I. A., Heagerty, P. J., & Koepsell, T. D. (2007). Release from Prison—A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates. The New England Journal of Medicine, 9.

Cox, R. (2018). Mass Incarceration, Racial Disparities in Health, and Successful Aging. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 42(2), 48–55.

Fairbanks, R. P. (2014). Recovering Post-Welfare Urbanism in Philadelphia and Chicago: Ethnographic Evidence from the Informal Recovery House to the State Penitentiary. In P. Sandermann (Ed.), The End of Welfare as We Know It? (1st ed., pp. 89–106). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Ginn, S. (2012). The Challenge of Providing Prison Healthcare. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 345(7875), 26–28.

Schoenfeld, H. (2016). A Research Agenda on Reform: Penal Policy and Politics across the States. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 664, 155–174.

Wildeman, C., Turney, K., & Yi, Y. (2016). Paternal Incarceration and Family Functioning: Variation across Federal, State, and Local Facilities. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 665, 80–97.

Related Posts

A Spoonful of (Modified) Sugar as an Antiviral Medicine

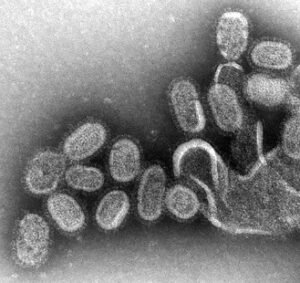

Figure 1: A negative stain transmission electron micrograph of Influenza...

Read MoreThe E.C.H.O. Initiative: Encouraging Cardiovascular Health Through Outreach

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreBad dreams? According to new studies, COVID-19 could be to blame

Figure 1: A sleeping child. When we sleep, we dream,...

Read MoreNishi Jain