For more related news, check out the UnknownNow, an organization for neuroscience research and service

Source: Bertollo et al., CC BY 4.0

Introduction

Humans have a natural tendency to be social. Social interaction allows individuals to meet their basic social and emotional needs, such as the need for companionship and intimacy. Recent years have seen the emergence of a social isolation crisis. Due to factors like the Covid-19 pandemic and the use of social media, many deep social interactions have been replaced by superficial connections1. These changes have been particularly detrimental to teens, with 21% presenting symptoms of anxiety2 and a reported 40% increase in feelings of loneliness3.

This article summarizes a research project where we used surveys, personal interviews, and an isolated experiment to understand how relationships are affected by social isolation. The purpose of this paper was to examine the effects of social isolation on human relationships and form a clearer understanding of its detrimental effects on the human brain. The full research paper can be accessed at this link.

Methods

The central aspect of the research paper was a rapid literature review of existing studies that explored the functional and structural impacts of social isolation on the growing brain. Several key terms were utilized to identify relevant literature in PubMed, which totaled to 34 scholarly articles. The articles involved the association linking development changes and teens’ relationships with one another; they contained studies of animals to illustrate the impact to the brain, highlighting its dire effects as well as its limitations for future studies to explore.

The chosen articles were reviewed by all authors to assess their relevance. The use of published scholarly sources allowed us to summarize existing knowledge and identify knowledge gaps that can be filled by future research.

To complement the literature review, surveys and personal interviews were conducted to gather additional relevant data. While the open ended survey questions allowed for more in systematic analysis of responses, the interviews allowed for analysis of body language. Some of the questions used for the interview are:

- What do you think, “having a relationship with another person is”?

- How important are relationships for you?

- What qualities do you look for in a relationship?

- Here’s another scenario: you notice your siblings acting different than usual, isolating themselves. You ask what’s wrong but they respond with “it doesn’t matter.” What’s your first reaction?

The interviews and surveys were performed periodically from May 1st to August 10, 2023 within the teens present within Adlai E. High School. The diverse school with over 4,500 students allows for large and statistically accurate data collection.

Results

In summary, the literature review highlights the pivotal role that social interaction plays in preserving cognitive function. The data paints a clear pattern of how isolation and a lack of mental stimulation can contribute to cognitive decline, deficits in attention, and problem-solving skills. For instance, persistent feelings of “overthinking” and “stress” can disrupt the equilibrium of neural circuits responsible for cognition and decision-making processes, as previously elucidated4. In particular, this study portrays how stress, often created by feelings of overthinking, causes an impending imbalance of neural circuitry subserving cognition, in turn affecting systemic physiology via neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune and metabolic mediators.

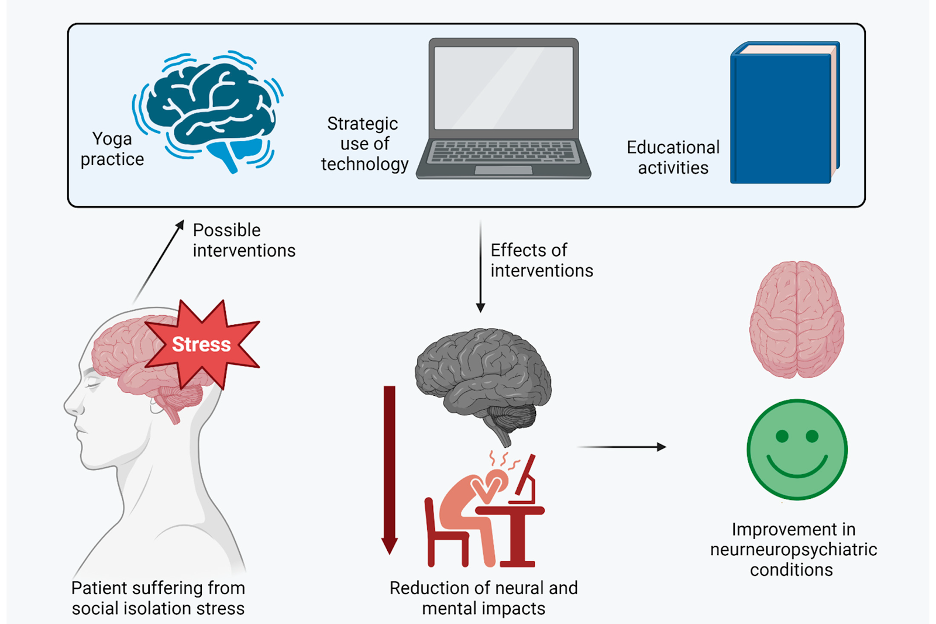

Regular social interaction nurtures brain plasticity – the ability of the brain to adapt and facilitate learning. Isolated individuals have more limited opportunities for new experiences and exposure to different perspectives, potentially reducing brain plasticity. Research on people and animal models together lay the groundwork for comprehending how specific interventions intended to enhance prosocial behavior and overall wellbeing may cause alterations in the brain related to plasticity. A growing body of research indicates that a variety of interventions, such as cognitive therapy, regular, moderate physical exercise, and interventions based on traditional contemplative practices, may cause changes in brain plasticity that lead to positive behavioral outcomes5.

Social connection also aids the regulation of emotional responses by acting as a buffer against negative emotions. Social isolation, in contrast, can disrupt the brain’s ability to regulate emotions effectively, forming heightened emotional reactivity. For example, prolonged isolation can trigger increased stress and anxiety levels, as explained above. This overstimulation can cause the brain’s stress response system to become overactive, leading to the extensive release of cortisol and affecting the neurochemical balance in the brain due to dysregulation of dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin. Imbalances in these neurotransmitters can contribute to feelings of sadness, anxiety, and reduced motivation to engage in social interactions, which could lead to depression and anxiety.6

In addition to imbalances in neurotransmitters, prolonged social isolation has also been shown to influence the structure of the brain. Studies in humans and animal models have shown that social isolation can lead to structural alterations in brain regions involved in social behavior and emotional regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. These changes may impact cognitive function, emotional processing, and social behavior. And because of these impacts, it ultimately affects their relationship and how they view, feel and interact7.

Social Isolation Impacts Introverts and Extroverts Differently

It is likely that introverts experience being alone differently than extroverts. The common understanding is that introverts tend to benefit more from time alone, with time alone allowing them to “recharge”, collect and understand their emotions. In contrast, extroverts are thought to be recharged by spending more time with other people. These behavioral differences are thought to depend on differential responses to dopamine between introverts and extroverts. The neurotransmitter dopamine is what drives us to look for rewards. Due to a heightened possession of dopamine receptors, extroverts are more inclined to seek out dopamine-releasing events. Due to their extensive engagement as exemplified in interviews. On the other hand, overstimulation is just what introverts try to avoid, cultivating in their fewer dopamine receptors than extroverts. This in turn causes them to be more sensitive to the negative effects of exciting situations. Recent research suggests that acetylcholine is also important. Christine Fonseca (2014) explained that acetylcholine works the same for introverts as dopamine does for extroverts. The difference is that introverts feel happiest when focused inside and acetylcholine allows introverts to “ relax and think deeply, which is what they need to “recharge” from overstimulation.” 8

When conducting our surveys and interviews at Adlai E. Stevenson High School, we were able to examine this relationship between introversion/extraversion and social behavior. The survey began with the question “How important are your relationships to you?”. Respondents were given a scale from 1-10 to rate their answers (10 being very important and 1 being not important at all) followed by two open-ended questions. The purpose of this structure was to slowly ease up the intensity of the questions to let the person open up, enough to provide relevant open-ended answers that provide data. The 1-10 scale was presented to provide qualitative data for groups to be formed. The questions consisted of participants’ perspectives on relationships, experiences when alone, and the impact of solitude on various aspects of their emotions and thought processes.

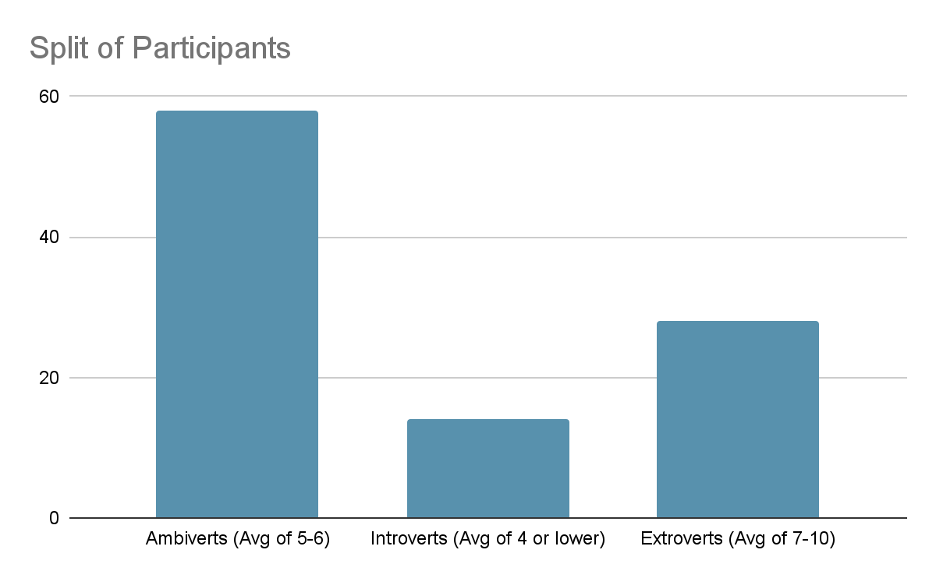

After collecting the data, we categorized it based on the average ratings provided by the participants. The ratings were divided into three ranges: an average of 7-10, an average of 5-6, and below 4 on average. This categorization allowed us to create a spectrum ranging from individuals who tend to enjoy social company (resembling extroverts), those who lean towards alone time (akin to introverts), and those with a balanced response (resembling ambiverts). We combined this categorization with the various aspects of the questions to capture a comprehensive view of the participants’ inclinations. Analysis of the data revealed a predominance of “ambiverts” at 58%, followed by those favoring social interaction at 28%, and a notable minority of “introverts” at 14%.

Figure 1. This graph describes the split of participants who participated in the surveys.

Regarding participants who fell within the 7-10 average category, indicative of a more sociable and extroverted disposition compared to the rest of the dataset, their responses exhibited a lower rating for positive emotions such as feeling uplifted and energized during scenarios involving extended periods of isolation. Conversely, when questioned about their negative emotions after being alone, their ratings were notably higher. For instance, a significant majority of subjects assigned scores around 8-9 to feelings of burnout following solitary periods. These responses provided insights into their emotional dynamics within social settings. Interestingly, they displayed reduced levels of “awkwardness” (with ratings below 4) when contemplating interactions with familiar or unfamiliar individuals, indicating a diminished positive sentiment. Despite these findings, certain attributes such as patience and productivity emerged as elevated after moments of solitude in the individuals rated as extroverts. These individuals also tended to provide more extensive responses to the open-ended questions, offering insights into their perspectives and thoughts about relationships. They demonstrated heightened qualities such as understanding, being dependent on social relationships, and happiness when interacting with others.

This dataset illuminates a pattern in which individuals inclined towards social engagement exhibit a lesser inclination for solitude, yet derive positive outcomes from it—such as improved mood and feelings of productivity—even if the experience itself isn’t always optimal. This analysis suggests that such individuals play an active role in their relationships, relying more extensively on them. Furthermore, they exhibit a willingness to express their thoughts and emotions, as evidenced by the depth of their responses to open-ended inquiries.

Conversely, the subjects falling under the below 4 average ratings, categorized as introverts, or individuals who benefit from alone time, demonstrated a higher rate of positive feelings after they spent alone time. For example, they expressed ratings of 8 when asked how they feel when they’re alone, and above 7 when considering their level of energy and capacity for prolonged isolation. Additionally, they reported an increase in productivity and patience during these phases. Correspondingly, their ratings for feelings of “dread” or “awkwardness” when interacting with unfamiliar individuals were 5 or below, underscoring their reduced discomfort in such situations. Interestingly, this group offered the most extensive responses to the open-ended questions, providing rich insights into their perspectives on relationships. This suggests that upon thoughtful reflection guided by the ratings, they were most inclined to open up and share their feelings. Their responses indicated a profound consideration of relationships, demonstrating a meticulous approach to how they perceive and interact within them. This underscores their capacity to place considerable value on the quality and influence of their relationships. Despite esteeming relationships, their periods of isolation hold equal, if not greater importance. This illustrates that although certain adolescents derive preference and benefit from extended periods of alone time, their relationships remain a priority. It’s noteworthy, however, that they appear to have more reserved expectations and anticipate less from relationships compared to the previous group.

The mixed batch of responses (the ‘ambiverts’), rated between an average of 5-6, often displayed the shortest of the open-ended questions, showing that they were less likely to open up compared to the other groups. They distanced from providing any examples, or sharing personal experiences on likes and dislikes, but rather answered the question promptly. This pattern highlights that while these adolescents possess an open disposition and diverse feelings concerning solitude and social interaction, articulating their sentiments remains a challenge. This observation hints at potential struggles they face in defining and managing their perspectives on relationships, perhaps due to the nuanced nature of their responses.

Isolation’s effects on relationships exhibit variations among these distinct groups. The responses from the extroverts, irrespective of their personality traits or confidence levels, those who generally enjoy social interactions and experience negative emotions after isolation, reveal that prolonged periods alone can deteriorate both their relationships and self-perception. Conversely, individuals who find solace in isolation often exhibit a reserved perspective on relationships, yet demonstrate a remarkable willingness to open up. This contrasts with the mixed group of responses, the ambiverts, who struggle to articulate their views and feelings on relationships. This challenge indicates an absence of firmly established opinions, needs, feelings, or desires in their relationships. Consistent difficulty in expression and communication may consequently lead to diminished relationship value. This scenario prompts the question of whether isolation could hold benefits for some while proving detrimental for others, potentially limiting self-awareness about these emotional domains. Notably, despite the contrasting tendencies of these three groups, they collectively indicate an increase in certain positive emotions and behaviors—such as patience and productivity—following periods of isolation . This alignment arises due to the survey’s design, which encouraged more comprehensive responses. Consequently, while perspectives on alone time and relationships distinctly vary, they converge when it comes to fostering positive behavioral development. Isolation undeniably impacts individuals differently based on their group affiliations, yet yields similar outcomes.

Interviews

To further enrich the presented data and bolster the findings, a series of interviews were conducted to gather personalized insights into individuals’ perceptions of relationships and their responses to various social scenarios. These interviews adhered to ethical guidelines, featuring informed consent processes, as well as measures to safeguard participants’ confidentiality and well-being. The interviewees were exclusively high school teenagers, a group in the crucial stages of brain development. The interview questions were structured to progress from inquiries about personal attributes to probing various aspects of relationships and concluding with questions concerning hypothetical situations. This sequence allowed participants to first reflect on their values, subsequently linking them to their views on relationships and associated emotions, and finally delving into their potential actions in diverse scenarios. The interviews were meticulously observed, with both behavioral patterns and facial expressions meticulously recorded to provide a comprehensive evaluation. These behavioral shifts during the interviews aimed to illuminate the brain structures that were engaged (expounded upon later) and their transformations while processing the presented situations. Notably, participants were once again categorized into the aforementioned generic groups to facilitate data organization.

A majority of the interviewed participants exhibited a blend of hope, determination, and occasional stress. Participant 1, for instance, showcased attributes of ambition, resilience, and hope. When posed with the question “Do you believe good things will happen for you?”, an emphatic “yes” resonated. When connecting these emotions to their perspective on relationships, they revealed significant regard for relationships while sometimes choosing not to actively engage during challenging situations. For instance, despite caring about familial reactions and siblings, a tendency to withdraw emerged, albeit with underlying concern. This inclination to retreat surfaced when faced with judgment and a lack of confidence (Paul, 2019). The participant demonstrated a range of reactions including nods, shrugs, and facial touches, indicating excitement and interest initially, followed by rapid eye movements and swift responses, signaling disinterest. These reactions and responses align with the characteristics of the previously mentioned ambivert group. They manifest a diverse spectrum of emotions across different scenarios, yet maintain a guarded approach. While valuing social connections, they exhibit a willingness to step back, revealing tendencies toward restraint and offering concise answers. This trend is echoed among various other interviewees displaying similar behavioral patterns. Another participant, for example, exhibited emotions of happiness, aspirations, and determination, paralleled by a noteworthy emphasis on relationships combined with a sense of mutual effort. The uniformity of body language throughout the interview further implies openness tempered by moments of retreat. Consequently, this subgroup, the ambiverts, seem to derive satisfaction from both solitude and social interaction, without causing detrimental effects on their relationships.

Upon discerning that ambiverts comfortably navigate both solitude and social contexts without inflicting negative impacts on their relationships, it becomes apparent that the relationships they form might remain unscathed, yet possibly lack deeper intimacy. This equilibrium between alone time and social engagement influences the depth and stability of their interpersonal connections due to their tendency to retreat.

Conversely, a different participant, categorized as an “extrovert,” displayed a profound sense of joy and placed extreme importance on their relationships, offering intricate insights into their needs and values. This orientation significantly influenced their interactions, including those with siblings and family members. When confronted with situational inquiries, they exhibited considerable empathy and a sense of responsibility both toward their feelings and those of others. Furthermore, participants like this one encountered challenges when confronted with periods of solitude, which subsequently affected their self-perception and their capacity to engage with others. For instance, another participant revealed a tendency to “overthink,” questioning themselves with thoughts like “What did I do wrong,” often leading to a gradual withdrawal. This pattern unmistakably establishes a connection between highly active engagement in relationships and a deep sense of purpose within them. Consequently, the experience of isolation directly impacts such individuals in a negative manner, evident in their responses to the isolation scenario.

Conversely, the final group, the “introverts,” as anticipated, demonstrated a complete contrast. Although the quantity of collected data wasn’t as extensive as with the other groups, there existed sufficient evidence to outline a clear trend. These participants conveyed emotions characterized by a sense of responsibility, anxiousness, and a limited degree of hopefulness. These sentiments profoundly influenced their role within relationships and their social interactions. For instance, many expressed a preference for staying at home and frequently described feeling “drained” following a day spent outdoors. When prompted to elaborate on their course of action in challenging relationship scenarios, their responses revolved around waiting, providing passive support, and similar approaches. Additionally, they revealed feeling “annoyed” or “irritated” at the prospect of engaging with others after a long day of work, yet conversely, they experienced “energized” and “happy” emotions after dedicating time to themselves. This pattern unequivocally establishes that this group thrives in solitude, deriving significant benefits from time spent alone, while social interactions tend to have the opposite effect. Notably, despite their sense of rejuvenation following solitary moments, they seem to maintain a reserved level of engagement in their relationships, implying a measured participation even as they report feeling “recharged” after time alone.

Discussion

The literature review revealed that while some alone time can be beneficial, and some individuals naturally desire more alone time than others, it may lead to decreased involvement in relationships, excessive alone time can have a range of negative psychological effects. While solitude can offer opportunities to recharge, maintaining social connections is crucial for overall well-being. Social isolation has complex effects on brain function, structure, and emotional health. Social isolation can hamper brain plasticity, leading to cognitive decline and emotional disturbances. Human studies demonstrated cognitive deficits and emotional dysregulation due to isolation, while animal studies showed brain anatomical abnormalities.

To expand on the findings of the literature review, it would be useful to collect additional data and perform more extensive interviews or surveys. Nevertheless, the findings emphasize the significance of social connections and prompt further research into additional impacts beyond brain structure and neurochemistry. These insights benefit various fields like neuroscience and psychology and inform the public about the detrimental effects of social isolation. Future research should focus on the long-term effects of social isolation, especially in adolescents.

Based on these findings, new approaches to mental health support and social engagement should be considered, tested, implemented, and promoted widely. Social interactions, even online interactions, can reduce loneliness. Efforts to boost social engagement, in whatever form, should be implemented alongside efforts to promote stimulating environments, exercise, meditation, and brain games. Together, these interventions stand to improve brain plasticity and cognitive health. A balanced diet, good sleep hygiene, and psychotherapy can all contribute to well-being. Resilience to isolation varies among individuals, influenced by coping techniques, psychological traits, genetics, and prior experiences. Interventions tailored to individual needs are crucial for mitigating isolation’s effects.

References

- Nair, M. (2020). Is Society Too Dependent On Technology? 10 Shocking Facts. University of the People https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/society-too-dependent-on-technology/

- KFF. (2024). Roughly 1 in 5 Adolescents Report Experiencing Symptoms of Anxiety or Depression. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/press-release/roughly-1-in-5-adolescents-report-experiencing-symptoms-of-anxiety-or-depression/.

- Loneliness in young people: research briefing. Mental Health Foundation https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/public-engagement/unlock-loneliness/loneliness-young-people-research-briefing.

- McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress 1.

- Davidson, R. J. & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 689.

- Hostinar, C. E. & Gunnar, M. R. (2015). Social Support Can Buffer against Stress and Shape Brain Activity. AJOB Neurosci. 6, 34.

- Vitale, E. M. & Smith, A. S. (2022). Neurobiology of Loneliness, Isolation, and Loss: Integrating Human and Animal Perspectives. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16.

- Embracing the Introverted Brain – Mind Brain Education. https://www.mindbrained.org/2020/02/embracing-the-introverted-brain/.

Related Posts

The Public Health Humanitarian Crisis in Ukraine

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreThe Public Health Implications of Chronic Kidney Disease in San Diego

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2024...

Read MoreThe “Old Friends” Hypothesis and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Authors: Sakeena Badrane1, Vivek Babu2, Sanah Handu1 1University of Pittsburgh,...

Read MoreCaribbean History through Genetics and Archaeology

Figure 1: A map of the Caribbean Islands from 1894...

Read MoreThe Influence of Language on the Perception of the World

Figure 1: The Influence of Language on the Perception of...

Read MoreRetitling Stress: A Look at the Yerkes-Dodson Law

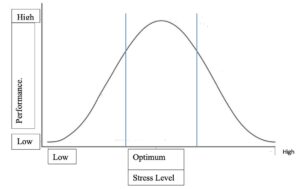

Figure 1: This graph compares stress level with performance at...

Read MoreAkshaya Ganji