From Nepal’s bengal tiger to Kenya’s big Lions, conservation of large carnivores is a substantial challenge. And researchers have found that oftentimes locals’ preconceived notions and attitude towards these big carnivores may only make it worse.

On a hot and dry day in Northern Kenya, Tim Noonan, an extreme videographer, was visiting a special group of people who hunted lions for hundreds of years: the Samburu tribe. He interviewed Dipa Lenanyangera, a 40 year old tribesman, who proudly claimed to have killed three big lions. Dipa and his tribe believe lion killing to be their traditional right. They consider themselves as fearsome lion warriors.

But things have changed now.

The region is losing its lion population at an unprecedented rate and the Samburus are worried.

Figure 1: Samburu Tribesman in Northern Kenya

Source: Alex Strachan at Pixabay

Emanuel, a local from Samburu’s neighbouring village, is also a lion killer. But unlike Samburus he is not worried. In 2014, when a lion attacked his village and killed 18 herds of sheep and goats, he couldn’t hold the frustration within. He led a lion lynch mob, cornering and ultimately killing three big cats.

For some, lion killing is a tradition; for others it’s about saving their livestock, the lifeblood of the Samburu economy.

Even beyond the Samburu tribe, the conflict between human lifestyles and the survival of lion populations is a problem that resonates among several African nations. And the situation is only getting worse due to the changing climate, harsh human attitude, retaliatory killings, and habitat encroachment. Notably, long lasting droughts force the lions and livestock to aggregate near common water sources leading to an increased likelihood of conflict.

Figure 2: A male lion stares

Source: Pixabay

But what actually triggers a harsh attitude for lions among locals? Fikirte Gebresenbet, a researcher affiliated with Oklahoma State University, surveyed the locals around Gambella National Park of Ethiopia. She found that locals were harsh to lions not only because they lost livestock due to lion attack, but also because they lacked basic education, owned larger flocks of livestock, and/or were victims of livestock theft (Gebresenbet, 2018).

Despite locals’ harsh attitude towards lions, she found that lion attacks haven’t been the main cause of livestock loss. In fact, the threats of disease and theft contributed a big portion. Even if locals claimed that lion attacks were increasing, the researcher found no tangible evidence. The last reported act of lion depredation was a decade ago and the last recorded human attack was twenty years back.

Despite all this, more than half of the people suggested lion killings be legalized and about a quarter of people wanted lions to be extirpated from the region.

This blame game and harsh attitude have been a big problem for Africa’s topmost predators.

But there is also hope.

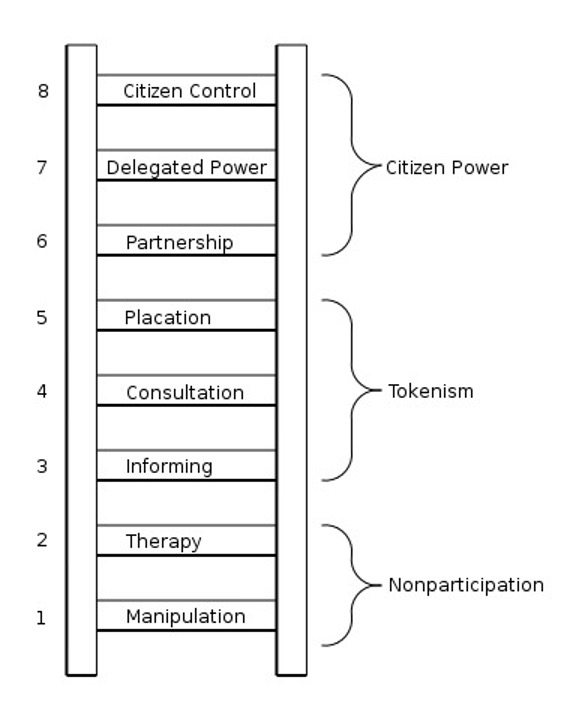

Scientists hope a unique approach called ‘Arnstein’s ladder of participation’ (Arnstein, 1969) can save lions before it’s too late. It can potentially help communities to live in harmony with big carnivores. For which, first the locals are educated about conservation importance. Then are consulted and trained with forest management skills. And finally encouraged to participate in decision making and leadership of the project.

Figure 3: Arnstein ladder of participation

Source: Wikimedia Commons

There is evidence that this approach is working.

Samburus used to be the proud lion killers. Now they are proud conservationists. “If there are no lions, then there is no Samburu. I used to dream of being a lion warrior, now I am a protector”, Said Jeneria Lekilelei, a local from Samburu who now leads a Lion watch project. His team deliberately monitors lion movement and informs locals before letting any livestock graze around the buffer zone. This process has helped avoid potential conflicts.

So it is indeed necessary that given the gravity of lion endangerment; researchers, indigenous African tribes, and governments should work together to conserve these topmost predators before it’s too late.

References

Gebresenbet F, Bauer H, Vadjunec JM, Papeş M. (2018). Beyond the numbers: Human attitudes and conflict with lions (Panthera leo) in and around Gambella National Park, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204320

Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. JAIP, Vol. 35, pp. 216-224.

Related Posts

Nuclear Fusion Startup May Hold the Key for Long-Term Nuclear Fusion

Figure 1: The image above shows the steps for inertial...

Read MoreUnderstanding the Social Factors Affecting Cancer Therapy

Cover Image: A patient being prepared for radiation therapy. (Source:...

Read MoreCOVID-19 Clinical Trials and Racial Disproportionality

Figure 1: A doctor drawing blood from a patient as...

Read MoreSaugat Bolakhe