This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023 Summer Program.

Source: Robina Meermeijer

Introduction

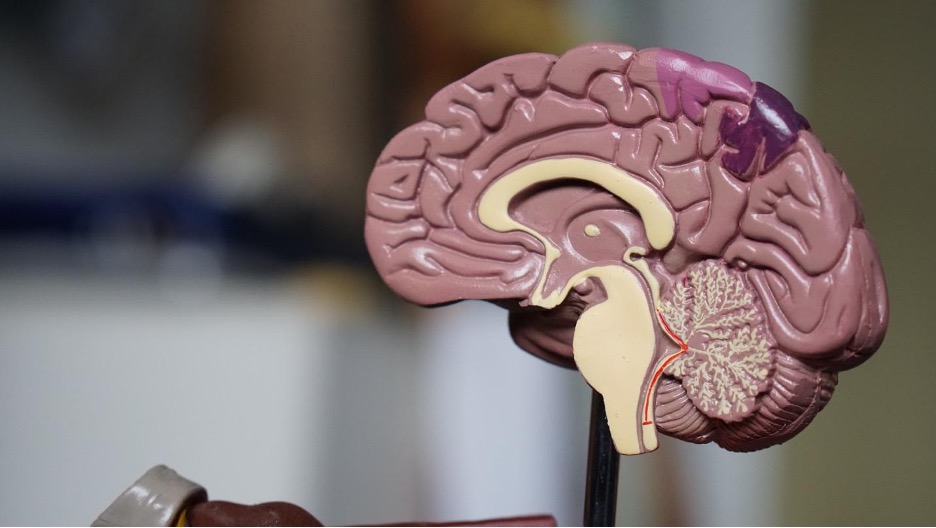

We as humans have a thirst for connection. Connecting with other humans, connecting with ourselves, or connecting through information. Our capacity for connection, however, is a delicate fabric, dependent on our mental state. Alzheimer’s Disease damages one’s mental state to the point where connection progressively becomes impossible.

Our country channels substantial resources into public health: roughly 4.3 trillion dollars in total, and 305 billion on Alzheimer’s alone1,2,3; yet Alzheimer’s is still a disease in search of an effective treatment. More than 6 million Americans of all ages have Alzheimer’s4. Their everyday life is interrupted with memory loss, changes in emotional responses, personality and behavior changes4.

While most of these individuals are white Americans, evidence suggests that African Americans and Hispanics are underdiagnosed and may actually be at a higher risk of developing the disease. Similarly, a recent study from the University of Miami suggested that a combination of socioeconomic factors (e.g., lower average income, poorer access to healthcare) results in medical factors (e.g., higher rates of developing heart disease and diabetes) which are risk factors for Alzheimer’s5,6.

Furthermore, heavy stigma and negative beliefs affect individuals with Alzheimer’s by impacting diagnosis rates and their overall health. As of right now, Black Americans are more likely to forgo participating in clinical trials. A recent survey from the Alzheimer’s Association7 found that,

- “55% of Black Americans think that significant loss of cognitive abilities or memory is a natural part of aging rather than a disease.”

- “Only 53% of Black Americans believe that a cure for Alzheimer’s will be distributed fairly, without regard to race, color or ethnicity.”

- “The fear of being a guinea pig, which 69% of Black Americans name as a concern.”

- “Black Americans are also far more likely than other racial groups to be concerned about getting sick from treatment, with 45% describing this as a reason.”

- “However, Black Americans are the least likely group to report cost as a concern, with only 24% saying cost and time are reasons not to participate.”

If those with early signs of cognitive difficulties were to overcome these concerns, their primary care provider is likely the first medical practitioner they would contact8. However, primary care physicians often report a lack of time and confidence in identifying and caring for patients with Alzheimer’s disease9. They instead send patients to specialists, who may or may not be available, especially for Americans with lower levels of income9,10.

Current Community Interventions

Thus far, there have been various public health efforts to address these issues. One example are life course approaches. Life course theory involves studying and understanding the ways in which people live and how various factors affect them. It is a method in which researchers analyze how someone’s initial experiences affect them as they age. Life course approaches are often driven by the findings of research studies, which often produce helpful diagrams that share these findings in an accessible way.

For example, one study used the life course perspective to study the initial diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, specifically from the perspective of caregivers. They focused on the four dimensions of the LCP: family history, linked lives, human agency and organizational effects, and the ways in which these dimensions point to differing types of entry into the illness trajectory. The use of life-course approaches is not only helpful for illuminating the experiences of people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers, but also bring communities closer together. They can aid in risk reduction, early detection, and the provision of safe, quality care11,12.

Another active effort underway is the Alzheimer’s Association and American College of Radiology’s “NEW IDEAS” clinical trial on mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia11,13. The objective of this trial is to use medical imaging to detect early signs of cognitive impairment. The trial plans to achieve this by enrolling 7,000 Medicare participants who have cognitive impairment. To ensure diversity, they enrolled a diverse group of individuals: “at least 2,000 Blacks/African Americans, at least 2,000 Latinos/Hispanics, and up to 3,000 additional participants from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

Even if a person is unable to join “NEW IDEAS”, they can still contribute to Alzheimer’s research through other studies. The Alzheimer’s Disease Association’s TrialMatch system is a free and private tool that connects Alzheimer’s patients, caregivers, and healthy volunteers to scientific studies11,13,14. To target African Americans specifically, the UsAgainstAlzhiemers15 organization strives to prevent, educate and support individuals in communities of color that have or will be impacted by Alzheimer’s.

They make an effort to focus on Alzheimer’s prevention instead of taking action only after a serious diagnosis occurs. Having a platform in which active preventative strategies are being implemented allows for lower cost in treatment for patients and improvement in their overall health.

Proposed Community Interventions

As long as Alzheimer’s remains a prevalent and pressing issue in our society, implementing community public health interventions that build on previous ones are of the utmost importance. The simplest way to start is by spreading awareness about the limited research or programs that explore the health implications of Alzheimer’s. Further expanding Alzheimer’s awareness on major entertainment networks, especially for underdiagnosed populations, would be especially helpful16. Once the magnitude of the problem is clear, community collaborations like interactive workshops that are available on a seasonal basis, advertisements and discussions at major social gatherings and workplaces are critical. To teach the younger generation about the risk factors of Alzheimer’s, improving the school curriculum around public health with annual guest speakers, presentations, and information sheets taken home by students would have a large impact. Through these simple, yet extremely direct actions will bring the proactive response that is needed for this cause.

References

- Using the life course perspective to study the entry into the illness trajectory: The perspective of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. (2010). Sci. Med. 70, 1501–1508.

- https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical#:~:text=U.S.%20health%20care%20spending%20grew,spending%20accounted%20for%2018.3%20percent. .

- Schneider, E. C. et al. Mirror, Mirror 2021 – reflecting poorly: Health care in the U.S … The Commonwealth Fund (2021). Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/Schneider_Mirror_Mirror_2021.pdf. (Accessed: 2nd July 2023)Schneider, E. C. et al. Mirror, Mirror 2021 – reflecting poorly: Health care in the U.S … The Commonwealth Fund (2021). Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/Schneider_Mirror_Mirror_2021.pdf. (Accessed: 2nd July 2023).

- What is Alzheimer’s? Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers.

- Race, Ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s. https://aaic.alz.org/downloads2020/2020_Race_and_Ethnicity_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- Hemlock, D. Study Shows African Americans and Hispanics Have Greater Vulnerability to Alzheimer’s Because of Vascular Risks, Socioeconomic Factors. (2022). InventUM | University of Miami Miller School of Medicine https://physician-news.umiamihealth.org/study-shows-african-americans-and-hispanics-have-greater-vulnerability-to-alzheimers-because-of-vascular-risks-socioeconomic-factors/.

- Black Americans and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia https://alz.org/help-support/resources/black-americans-and-alzheimers.

- Blair, E. M. et al. (2022). Physician Diagnosis and Knowledge of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimers. Dis. 85, 273.

- de Levante Raphael, D. (2022). The Knowledge and Attitudes of Primary Care and the Barriers to Early Detection and Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Medicina 58.

- Tzartzas, K. et al. (2019). General practitioners referring patients to specialists in tertiary healthcare: a qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 20.

- Jones, N. L. et al. (2019). Life Course Approaches to the Causes of Health Disparities. J. Public Health 109, S48.

- Public Health Approach to Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia https://alz.org/professionals/public-health/public-health-approach.

- Race, Ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s in America. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-special-report-2021.pdf.

- TrialMatch: Find Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s and Other Dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/research_progress/clinical-trials/trialmatch.

- AfricanAmericansAgainstAlzheimer’s. UsAgainstAlzheimer’s https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/networks/african-americans.

- Isaacson, R. S. et al. (2018) Using social media to disseminate education about Alzheimer’s prevention & treatment: a pilot study on Alzheimer’s universe (www.AlzU.org). Commun. Healthc. 11, 106.

Related Posts

The Public Health Humanitarian Crisis in Ukraine

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreThe I.D.E.A. Initiative: Infectious Disease Educational Awareness

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreAccording to New Research, Blue Whale Migrations Can Be Studied Through Song

Figure 1: A blue whale’s fluke (tail fin) sticks out...

Read MoreHow Many Humans Does it Take to Host a Planet?

Figure 1: This is an artist’s rendering of a potential...

Read MoreNeuroscience, Narrative, and Never-Ending Stories

Figure 1: A field of poppies. The myths of Persephone...

Read MoreAkshaya Ganji