Cover Image: A patient being prepared for radiation therapy. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Rhoda Baer)

INTRODUCTION

Something we should all be cognizant of is the lack of inclusivity in both cancer trials and in post-marketing drug sales. This is a problem which often owes to economic disparities: those with fewer resources have poorer health and well-being (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008). But the disparity also depends significantly on certain socio-cultural factors such as race and ethnicity The patterns of disparities in health care for minority groups – in terms of accessibility and affordability – are discussed in this article.

Race, Clinical Trial Accessibility, and Medical Disparities

Due to stringent policies that dictate who can become a subject in clinical trials, the number and characteristics of patients who enroll are often quite limited. In most cases, this group of patients are those with membership in support groups that have connections with either hospitals or companies offering these treatments (Unger et al., 2013). Disparities may be further exacerbated by a lack of publicization of clinical trial openings. And they also have a social dimension, founded on negative beliefs about treatment course and outcome. One such belief is the claim that air exposure during lung cancer surgery might cause tumour spread, which is especially prevalent among the African American community. This belief has been found in one study to negatively impact the willingness of African Americans to undergo surgery (Margolis et al., 2003).

Racial and ethnic considerations are deeply involved in the dynamics of cancer treatment. In most cases, race and social class are closely intertwined and are therefore given a joint consideration.

Huge racial disparities exist in early stage diagnosis with African Americans having higher mortalities than other groups in the US (Hayanga, 2009). For example, one study found that of 677 women suffering from breast cancer who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, 21% were reported to have foregone recommended adjuvant therapy (additional chemotherapy to enhance the effects of surgery). Of this 21%, 16% were white, 34% black, and 23% Hispanic. From these results, the authors conclude that minority women with early-stage breast cancer have double the risk of white women for failing to receive the necessary adjuvant therapies despite similar rates of consultation (Bickell et al., 2006).

Many epidemiologic studies have statistically demonstrated the limited explanatory power of the “known” biologic and social factors for the racial/ethnic differences in cancer incidence, morbidity, mortality, and quality of life and speculate that unmeasured cultural factors may be better indicators for these differences (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010).

Drug Affordability and Socioeconomic Status

Due to a number of factors – from the highly technical expertise required for new drug development to investors’ need for profits in order to continue funding research and development – medical treatments have incredibly high prices. High costs result in disparities in health and well-being within countries and between countries. Cancer treatment, one study has found, is less affordable in low and middle-income countries than high-income countries (Goldstein et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been shown that lack of good insurance is associated with more advanced disease stage at diagnosis , perhaps due to the fear of financial burden associated with it (Halpern et al, 2008).

High cost of treatment is especially a problem for cancer patients, often requiring them to resort to out of pocket settlements or co-payment strategies to supplement insurance reliefs. In a study that covered a 7-year period concerning the prevalence of out-of-pocket financing among patients, 13.4% of patients with cancer had high total financial burdens(health expenditures exceeding 20% of annual income) , in contrast to 9.7% among those with other chronic conditions and 4.4% among those without chronic conditions. In the United States alone, individuals diagnosed with cancer are 2.7 times more likely to declare bankruptcy, than individuals without cancer (Bernard et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2017).

However, other researchers analyse the concept of cost with that of drug efficacy in potential clinical benefits. Some drugs that are easily affordable have proven to have low efficacy and are therefore quite expensive in the long run due to continued illness with a sustained drug regimen (Durkee et al., 2015).

Reducing Health Disparities: Project Community

It is not that most cancers selectively target a particular demography, but rather that a lack of awareness / socio-economic reasons deter diversity in cancer trials. How, then do we address the lack of diversity in cancer trials? What efforts are being made to enroll African-Americans, the Hispanic population, and the Native American population – historically undertreated minority groups in the United States – in clinical trials? The FDA, which plays an important oversight role in drug development, has taken a keen interest in addressing these issues by launching Project Community

According to the FDA’s official website, Project Community is a nationwide initiative going to introduce the work of FDA oncologists and haematologists (cancer doctors) to people in local communities (Project Community | FDA, n.d.). The main objective of the initiative is to increase minority participation in clinical trials and to promote knowledge and minority participation in genetic databases. So far some of these efforts have borne fruit by increasing cancer awareness among underserved and under-represented community members about the need to increase cancer screening and availability of clinical trials.

The contributions to the genetic database by minority ethnic groups will go a long way in aiding oncology precision medicine. In the long run the initiative is projected to attract, and retain, a pipeline of diverse and qualified candidates for drug trials through targeted outreach (Project Community | FDA, n.d.).

Conclusion

It is evident that to understand the influence of culture on cancer, it is first necessary to dismantle the assumption that socioeconomic factors trump race, culture, and ethnicity. Instead, it is the interaction of all these factors that determines health disparities, and a better understand of these factors will increase the scientific basis for clinical practice and research among diverse populations. The social determinants of health, such as education, occupation, social status, housing, availability of quality services, health literacy, and degree of integration into a community social network act as powerful factors affecting cancer outcomes. And unlike the more rigid, biological determinants of health outcomes, these social factors are ones that we have far more power to address.

References

- Adler, N. E., &Rehkopf, D. H. (2008). U.S. Disparities in Health: Descriptions, Causes, and Mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852

- Bernard, D. S. M., Farr, S. L., & Fang, Z. (2011). National Estimates of Out-of-Pocket Health Care Expenditure Burdens Among Nonelderly Adults With Cancer: 2001 to 2008. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(20), 2821–2826. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522

- Bickell, N. A., Wang, J. J., Oluwole, S., Schrag, D., Godfrey, H., Hiotis, K., Mendez, J., &Guth, A. A. (2006). Missed Opportunities: Racial Disparities in Adjuvant Breast Cancer Treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(9), 1357–1362. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799

- Blackandwhitephotoofwomanreceivingavaccine(48546134757).jpg (2250×3100). (n.d.). Retrieved February 5, 2021, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Black_and_white_photo_of_woman_receiving_a_vaccine_%2848546134757%29.jpg

- Crawford, S. M., Sauerzapf, V., Haynes, R., Zhao, H., Forman, D., & Jones, A. P. (2009). Social and geographical factors affecting access to treatment of lung cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 101(6), 897–901. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605257

- Durkee, B. Y., Qian, Y., Pollom, E. L., King, M. T., Dudley, S. A., Shaffer, J. L., Chang, D. T., Gibbs, I. C., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J. D., & Horst, K. C. (2015). Cost-Effectiveness of Pertuzumab in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.9105

- Factors affecting patient participation in clinical trials in Ireland: A narrative review. (2016). Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 3, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2016.01.002

- Goldstein, D. A., Chen, Q., Ayer, T., Howard, D. H., Lipscomb, J., El-Rayes, B. F., & Flowers, C. R. (2015). First- and Second-Line Bevacizumab in Addition to Chemotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A United States–Based Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4904

- Goldstein, D. A., Clark, J., Tu, Y., Zhang, J., Fang, F., Goldstein, R., Stemmer, S. M., & Rosenbaum, E. (2017). A global comparison of the cost of patented cancer drugs in relation to global differences in wealth. Oncotarget, 8(42), 71548–71555. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17742

- Haas, J. S., Earle, C. C., Orav, J. E., Brawarsky, P., Neville, B. A., & Williams, D. R. (2008). Racial Segregation and Disparities in Cancer Stage for Seniors. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(5), 699–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0545-9

- Hayanga, A. J. (2009). Racial Clustering and Access to Colorectal Surgeons, Gastroenterologists, and Radiation Oncologists by African Americans and Asian Americans in the United States: A County-Level Data Analysis. Archives of Surgery, 144(6), 532. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2009.68

- Kagawa-Singer, M., Valdez Dadia, A., Yu, M. C., &Surbone, A. (2010). Cancer, Culture, and Health Disparities: Time to Chart a New Course? CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60(1), 12–39. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20051

- Margolis, M. L., Christie, J. D., Silvestri, G. A., Kaiser, L., Santiago, S., & Hansen-Flaschen, J. (2003). Racial Differences Pertaining to a Belief about Lung Cancer Surgery: Results of a Multicenter Survey. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(7), 558. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00007

- MEDICINE AND PUBLIC ISSUES Contemporary Unorthodox Treatments in Cancer Medicine A Study of Patients, Treatments, and Practitioners. (n.d.).

- Project Community | FDA. (n.d.). Retrieved January 24, 2021, from https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-community

- To mitigate, resist, or undo: Addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. (2000). American Journal of Public Health, 90(6), 867–872. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.6.867

- Unger, J. M., Hershman, D. L., Albain, K. S., Moinpour, C. M., Petersen, J. A., Burg, K., & Crowley, J. J. (2013). Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(5), 536.

Related Posts

A New Perspective on Treating Asthma

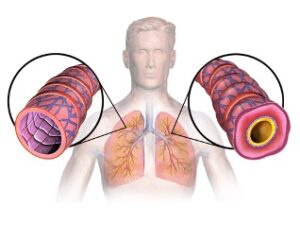

Figure 1: This diagram displays the results of tissue remodeling...

Read MoreWhen Bacteria Band Together – How Interactions Between Bacteria Can Change the Course of Disease

Source: Adrian Lange Bacteria are constantly fighting to preserve themselves;...

Read MoreCOVID-19 Pneumonia – A Different Illness Than Its Traditional Counterpart

Figure 1: This is an image of a child with...

Read MoreVaping and Mental Fog – The Connection Between E-Cigarette Use and Mental Function

Figure 1: Use of e-cigarette devices, like the one in...

Read MoreArtificial Intelligence for Mental Health Services

Source: Pavel Danilyuk In recent years, due to the pandemic...

Read MoreWhitney Nicanor Mabwi