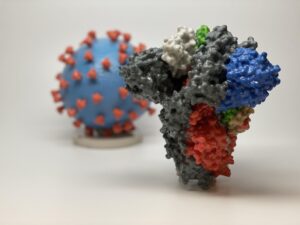

Figure 1: The race for a vaccine is in fully swing, as biotech companies are working against the clock to produce an effective and safe COVID-19 vaccine. The key question now is: who will get them?

Source: Wikimedia Commons

For the first time in U.S. history, not everyone who wants a vaccine, will get one. It is expected that by mid-December, the U.S. will be administering COVID-19 vaccines for approximately 20 million people. But this is far less than the number of people who are waiting in line (Reardon, 2020). With such a limited number of vaccines, the ethical dilemma of allocation is stark. How do you determine these 20 million people out of 300 million US residents?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP), a CDC panel that is responsible for deciding who these 20 million people will be, has determined that healthcare workers will be first in line to receive the vaccines. However, this isn’t a universal sentiment. In Britain, residents of long-term care facilities will receive the vaccines before healthcare workers. In the choice between healthcare workers and long-term residents, determining who comes first is evidently an ethical dilemma. Healthcare workers are on the front lines of this seemingly unremitting battle against COVID-19, risking their lives each and every day to save other people’s lives. By vaccinating them, a stable workforce will be ensured and, consequently, more lives will be saved. Thus, drawing on the ethical principal of utilitarianism—the belief that an action is ethical if it benefits the greatest number of people—it makes logical sense to prioritize healthcare workers (Duignan, 2020).

Across the pond, however, it is argued that since residents in long-term care facilities are at the highest risk of contracting and dying from the virus, they should be first in line. However, there is fear among some that side effects of the vaccine for these high-risk individuals may cause them to succumb to illness nonetheless (Reardon, 2020).

Deciding who will receive prioritization is challenging, and this difficulty extends to determining who will come after the first 20 million. After healthcare workers and senior citizens, other major at-risk groups include: the 87 million essential workers in the United States and individuals with high-risk medical conditions. When filling the next slot, it is critical to take into consideration vulnerability levels and the outsizing effect. It is also important to entertain logistical questions, such as: how will we determine which essential workers to vaccinate since all 87 million cannot be vaccinated and which pre-existing health conditions should be prioritized (Reardon, 2020)?

Additionally, many believe that underserved populations, which are predominantly Black and Brown communities, should be prioritized. It has been demonstrated statistically that these communities are more likely to contract and die from the virus. Also, it has been argued from a historical perspective that because these groups have been victims to the systematic injustices of the healthcare system, they further deserve to receive the vaccine at an early date (Reardon, 2020).

As is evident, there are many facets and complexities to this ethical dilemma of allocation, and it is up to the ACIP and, more importantly, state and local governments, to decide how they want to navigate these murky waters. They will need to determine when different groups of people are to receive the prized golden ticket: the long-awaited coronavirus vaccine.

References

Sara Reardon (3 December 2020). “Who Will Get COVID Vaccines First, and Who Will Have to Wait?” Scientific American. Retrieved 8 December 2020 from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/who-will-get-covid-vaccines-first-and-who-will-have-to-wait1/

Duignan, B., West, H.W. (2020). Utilitarianism. In B. Duignan (Ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica.

Related Posts

Factors in the Onset of Obesity – An American Public Health Crisis

Figure 1: Obesity is typically diagnosed based on BMI. The...

Read MoreN501Y COVID-19 Variants – Should We Be Worried?

Figure 1: 3D printed models of the SARS-CoV-2 virion (the...

Read MoreA Novel Mental Health Literacy Education Program for Pre-Teens

Figure: A typical elementary school classroom in Japan (Cassidy, 2005). Source:...

Read MoreAdithi Jayaraman