Covid 19 and Isolation (Source: created by author)

Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic has affected the lives of people across the globe in multiple dimensions, from health to work to social relationships. This review explores the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of adolescents. Even before the pandemic, the adolescent population was experiencing mental health issues with an increasing prevalence of depression. The transition away from in-person classes, face-to-face peer interaction, and physical activities has disturbed the overall lives of students and parents in ways that have exacerbated this negative trend. The protective measures against coronavirus, such as social distancing and lockdown, while positive efforts to protect the overall public health, are thought to have increased mental health issues among adolescents. This is especially true for adolescents who were already vulnerable due to previous mental health issues, special needs, and chronic physical conditions. In this article, several factors by which COVID-19 has specifically impacted adolescent mental health are reviewed in detail, including community-related risks, increased screen time and social media use, and challenges within the family.

Introduction

In the first half of 2020, the world stopped. The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in China in December 2019, rapidly spread across the globe, reaching almost 5.22 million deaths as of November 2021 (WHO, n.d.). The WHO declared the situation a pandemic, a label used for only the third time in history.

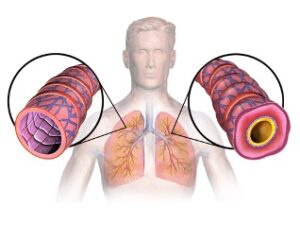

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is primarily spread from person to person through coughing and sneezing or close personal contact (WHO, 2020). COVID-19 is unique in that one person can have a wide range of symptoms, from fever and cough to muscle pain and diarrhea, while others can be mostly or completely asymptomatic. In the latter case, symptoms are mild and develop gradually, making the virus harder to detect and thus more easily transmitted.

The most effective way to react to such a pandemic is to minimize in-person contact between people. Thus, governments have implemented social distancing measures and even lockdowns in places where case numbers are high. This has included shutting down schools and businesses, limiting travel, and canceling social events. However, while minimizing illness and death due to the virus is an undeniable societal good, social distancing measures – in addition to the anxiety and other mental health symptoms induced by the spread of the virus itself – have contributed to the decline in mental health of the whole community, beyond only those infected. Symptom presentation of loneliness and depression, colloquially called “corona blues,” is a global issue that affects communities around the world. In particular, this paper will focus on the pandemic’s impact on the mental health of teenagers.

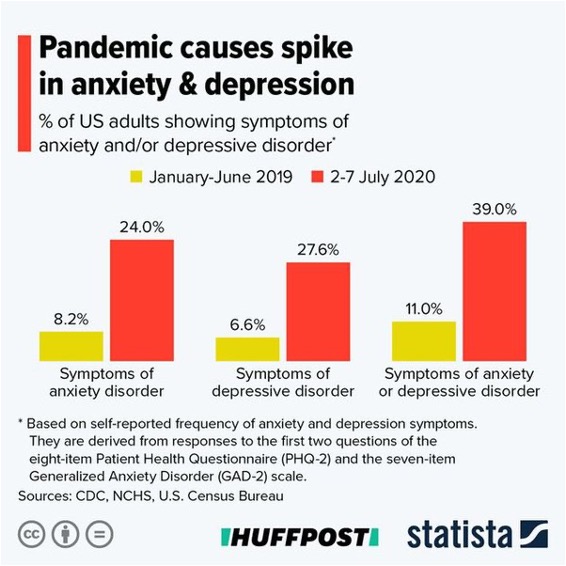

A recent survey of data compiled by the United States Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics showed that more than 4 in 10 U.S. adults reported symptoms of depression or anxiety by the end of 2020, a significant increase from the results of a comparable survey conducted in the first half of 2019. (Figure 1). Respondents displaying signs of anxiety or depression nearly quadrupled compared to pre-pandemic results.

Figure 1: COVID-19 impact on mental health (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Statista / Huffington Post)

According to a Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) tracking poll held in the US in mid-July 2020, 53% of respondents reported that their mental health had been negatively impacted after COVID-19 due to worry and stress over the crisis (Panchal, 2020). Specific symptoms included difficulty sleeping (36%), difficulty eating (32%), and increased alcohol/substance use (12%).

There are several factors contributing to these results. People may feel boredom, frustration, and a sense of isolation due to reduced social and physical contact with others and the inability to perform usual daily activities. Fear of infection is also associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety, especially in people experiencing any physical symptoms similar to those of COVID-19, such as coughing or muscle pain.

Additionally, economic status is also linked to negative mental health syptoms in times of the pandemic. The pandemic has led to economic recession in many countries as factories shut down, business meetings have been canceled, and consumers stayed home. The US officially entered an economic recession in February 2020. Accordingly, many people have experienced job loss or severe income reduction. Job loss and income insecurity increase risk of depression, anxiety, distress, and low self-esteem. In the KFF tracking poll related to COVID-19, a significantly higher share of households that lost income or went through unemployment had reported negative mental health impacts (Panchal, 2020).

Adolescent Mental Health Before the Pandemic

While COVID-19 has had severe impacts on mental health within the general public, teenagers and adolescents are particularly vulnerable. Important emotional and psychological developments occur during adolescence, a particularly rapid phase in human development. Adolescents undergo a period of relative mental instability and confusion as they transition into adulthood, and many experience emotional disorders such as depression, anxiety, excessive irritability, frustration, or anger (WHO, 2020).

Even before the pandemic, adolescent mental health was becoming an issue of increasing concern. Depression is a leading global cause of adolescent illness and disability (WHO, 2020). According to data from the Pew Research Center, 13% of teenagers in the US between the ages of 12 and 17 had experienced at least one major depressive episode in the past year (Geiger, 2019). Furthermore, the total number of teenagers who experienced depression increased by 59% from 2007 to 2017 (Geiger, 2019). In 2016, there were approximately 62,000 deaths due to adolescent suicide, making it the third leading cause of mortality among teenagers aged 15 to 19 years (WHO, 2020).

Impacts of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health

Across the globe, COVID-19 has damaged adolescent mental health. In the UK, adolescent health has been significantly impacted after the coronavirus breakout (Stewart, 2020). Samji and colleagues’ systematic review proposes that mental illness among adolescents and children is linked to the control measures taken for preventing the spread of coronavirus such as lockdown and social distancing. They have found a high prevalence of COVID-19-associated fear, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among adolescents, contrasting pre-pandemic times. The most frequently reported COVID-19-related worry was the dread of infection, either of oneself or, more typically, of infecting a susceptible family member or friend. Depression prevalence estimates ranging from 11 percent to 45 percent were reported in studies done during the peak of the epidemic in China (January–May 2020). (Samji et al., 2021).

There are several factors by which COVID-19 has specifically impacted adolescent mental health: community-related risks, increased screen time and social media use, and familial challenges. With people prohibited from going out to socialize, in-person interactions and communication are highly limited, thereby leading to social isolation. Peer connection is important especially for teenagers because when they feel distant from their parents, teachers, or other adults, they seek mental comfort with their peers. Teenage friendships help provide the belonging and acceptance because teens can relate to each other as they are in similar situations. Maintaining friendships is harder during pandemic circumstances because it is impossible to connect with friends on a daily basis at or outside of school. The absence of physical proximity or human contact between peers could contribute to mental illnesses such as depression or anxiety (Tang et all., 2021).

Furthermore, leisure activities such as going out in groups or joining sports and clubs have also been limited. A group of investigators led by Dr. Maria Loades, a psychologist from the University of Bath, found that “young people were as much as 3 times more likely to develop depression in the future due to social isolation, with the impact of loneliness on mental health lasting up to 9 years later” and that “this may increase as enforced isolation continues” (Walter, 2020). The research of Cohen and colleagues found that COVID-19 affected the mental health of healthy adolescents. They found negative mental health symptoms to be associated with various factors from the amount of time playing video games, decreased communication with peers, and poor sleep during lockdown. It was also found that healthy teenagers who depend on communication with their friends for coping and have trust in peer relationships were stressed more than the teenagers who did not count on peer relationships (Cohen et al., 2021).

Another contributor to worsened adolescent mental health during the pandemic is increased screen time and the use of social media. Social media and online communication could be seen as a positive outlet for teenagers to maintain social connection. However, in the long term, increased screen time can have adverse effects on mental health.

Fernandes and colleagues report that adolescents from different countries (UK, Mexico, Malaysia, and India) have started using streaming services and social media networks more after the pandemic (Wagner, 2020). The participants who scored higher on social media use, compulsive internet use, and gambling addiction also scored higher on pandemic-associated anxiety, poor sleep quality, aversion, loneliness, and depression. This signifies the significant impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the usage of the internet and the mental health of adolescents, irrespective of the country.

In addition, social media can be harmful to adolescents is through the spread of “fake news” and misinformation about COVID-19. It is difficult for adolescents in particular to distinguish between accurate and untrue information (de Miranda et al., 2020). In addition, health information associated with COVID-19 is constantly developing and recommendations are changing swiftly, providing many opportunities for untrue information to enter the social feeeds of adolescents. Furthermore, new sources of anxiety and stress specific to COVID-19 stem from social media sites. Consuming COVID-19-related information on social media can be overwhelming, frustrating, and anxiety-inducing. The fact that lack of social interaction during pandemic times might prevent adolescents from sharing their fears with others only serves to exacerbate this anxiety (Tang et al., 2021).

More generally, a review by the International Journal of Adolescence and Youth found that time spent on and investment in social media correlates with levels of depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and sleep problems (Keles, 2019). For instance, social media use can lead to lowered self-esteem due to self-comparison with others user, especially on the basis of physical appearance. The negative effects of social media on teenagers’ mood and anxiety has been well demonstrated in the literature (Dhir et al., 2018). When adolescents view carefully edited videos or images of their peers, they tend to make comparisons related to assets, lifestyle, and material well-being. Furthermore, social media users do tend to portray an idealized image of themselves through their online identities, so an individual’s life on social media often appears better than reality. As a consequence, teenagers might feel increased pressure to present a specific image of themselves to compete with others and receive social affirmation (Hamilton et al., 2020).

On top of all these issues, there are other dangers still for adolescents using social media sites. Social media can be a breeding ground for cruelty, and a platform to say things that one would never say in person. (Kokka et al., 2021). Also, adolescents are more likely to be exposed to inappropriate content, such as depictions of peers using drugs, vulgar remarks in the internet chat boxes, or engaging in self-harm (Muzi et al., 2021; Kar & Arafat, 2021).

Challenges within the family have also been an issue as many have been forced to stay at home with just their closest family members. There is an increased pressure on parents from multiple directions, one being the economic pressure of maintaining life expenses for the family. Due to the pandemic, many adults have gone through income insecurity, especially those who are in severely impacted industries such as catering, tourism, or travel. Many businesses have shut down, and as a consequence, many people have lost their jobs temporarily, or are still looking for work. Some families struggled to even feed their children because they were dependent on food stamps or school food programs (Wagner, 2020). Children of parents in precarious economic circumstances are less likely to have adequate resources to access the internet for remote education and communication with peers, which can play a protective role against mental illness (Crawley et al., 2020). According to a tracking poll by Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), many households in the US experiencing job or income loss reported that the stress led to negative health impacts such as difficulty sleeping or an increase in alcohol consumption (Panchal, 2020).

During the first year of the pandemic at least, parents also had the extra responsibility of supervising the education and activities of their adolescent children with little external support. S situations and emotional distress in parents often lead to more punitive attitudes towards their children. It has been established that a stressful home environment can increase the risk of child neglect and physical abuse (Patwardhan et al., 2017). Indeed, Fegert and colleagues highlight that child maltreatment risk has increased during the pandemic (Crawley et al., 2020). Sari and colleagues found that parents’ behavior became considerably harsher in contrast to pre-pandemic times. For example, a significant increase in harsh parenting behaviors was observed, including insulting and shaking (2021).

Impact on More Vulnerable, High-Risk Groups

Socially vulnerable adolescents who are more exposed to risks than their peers in terms of deprivation (lack of food, education, and parental care), exploitation, abuse, and neglect need special attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fegert and colleagues emphasize that mental health risks related to COVID-19 will disproportionately impact adolescents and children who are already marginalized and disadvantaged, such as children who already have a mental illness, low socioeconomic status, migrant status, trauma experience, and/or disability (2020).

One specific group of vulnerable individuals are those who live with domestic abuse. As economic instability generates feelings of helplessness and loss of power for all individuals, perpetrators of abuse tend to regain a sense of control and authority through violence (Fegert 2020). UN secretary Antonio Guterres has commented that there has been a “horrifying global surge in domestic violence” (Fegert 2020).

The rising trend in domestic abuse owes not only to heightened abuse behavior, but also to the social isolation brought about by protective measures. School closures exacerbate the problem of domestic violence because school is a protective place for children where they can report abuse (Clemens et al., 2020). With the shut down of schools, reaching out to protective adults and supportive communities became extremely difficult for children (Chatterjee et al., 2020). It is impossible for teachers to notice signs of domestic violence as they would under normal conditions and offer help.

Children or adolescents with previously existing chronic disorders or mental illnesses are another group of vulnerable people. For those with intellectual disabilities, it is difficult to understand the situation and why such restrictions on movement exist, leading to an increase in feelings of anxiety or agitation. Samji and colleagues claim that adolescents with chronic physical conditions and neurodiverse adolescents (including children with Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and autism spectrum disorder) are more likely to suffer from negative mental health outcomes (Samji et all.,2021).

Conclusion

Extended periods of quarantine during COVID-19 have severely impacted the mental health of the global population. And in this situation, adolescents have found themselves at a particular risk. There is an increased burden on families and limited access to external help such as health clinics, clidcare, and educational services. Behaviors that may be signs and aggravators of mental hardship under normal conditions, such as social and physical isolation, have become the norm. As a result, specific post-traumatic stress symptoms (confusion, anger, depression, and anxiety) have been found in higher levels in adolescents. Adolescent mental health has increasingly been a topic of focus over the past decade , but it’s exacerbation during COVID-19 has brought the topic to the surface and conveyed to the world that it is time for action. Governments and major community partners must collaborate in order to create long-term solutions for children and adolescents who are experiencing mental health crises during and after the epidemic. Examples of specific proposals include the provision of early diagnosis and treatment, training caregivers on home-based therapies, and establishing community outreach services to protect and care for their children’s and adolescents’ mental health, among others (Binagwaho & Senga, 2021). The world faced COVID-19 unprepared and off-guard. However, the pandemic could also provide opportunities for mental health services to develop in new ways, such as through increasingly-popular telehealth protocols. Additional research is needed to determine which methods are most effective, and it ought to be a high priority. It is essential that the issue of adolescent mental health is addressed to alleviate the pain of the many who are suffering.

References

Binagwaho, A., & Senga, J. (2021). Children and Adolescent Mental Health in a Time of COVID-19: A Forgotten Priority. Annals of Global Health, 87(1), 57. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3330

Chatterjee, S. S., Malathesh Barikar, C., & Mukherjee, A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian journal of psychiatry, 51, 102071. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102071

Clemens, V., Deschamps, P., Fegert, J. M., Anagnostopoulos, D., Bailey, S., Doyle, M., … & Visnapuu-Bernadt, P. (2020). Potential effects of “social” distancing measures and school lockdown on child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(2020), 739-742. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01549-w

Cohen, Z. P., Cosgrove, K. T., DeVille, D. C., Akeman, E., Singh, M. K., White, E., … & Kirlic, N. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health: Preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at-risk adolescents. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.622608

Courtney, D., Watson, P., Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B. H., & Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 Impacts on Child and Youth Anxiety and Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(10), 688-691. doi:10.1177/0706743720935646

Crawley, E., Loades, M., Feder, G., Logan, S., Redwood, S., & Macleod, J. (2020). Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000701. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701

de Miranda, D.M., da Silva Athanasio, B., de Sena Oliveira, A.C. and Silva, A.C.S., 2020. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents?. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, p.101845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

Dhir, A., Yossatorn, Y., Kaur, P. and Chen, S., 2018. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management, 40, pp.141-152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012

Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X. and Zhu, G. (2020) An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of affective disorders, 275, 112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

Elmer, T., Stadtfeld, C. (2020) Depressive symptoms are associated with social isolation in face-to-face interaction networks. Sci Rep 10, 1444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58297-9

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 14, 1-11. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1). doi:10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Fernandes, B., Biswas, U. N., Mansukhani, R. T., Casarín, A. V., & Essau, C. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Revista de psicología clínica con niños y adolescentes, 7(3), 59-65. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2056

Geiger, A., & Davis, L. (2019, July 12). A growing number of American teenagers – particularly girls – are facing depression. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/12/a-growing-number-of-american-teenagers-particularly-girls-are-facing-depression/

Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA pediatrics, 174(9), 819-820. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

Guessoum, S. B., Lachal, J., Radjack, R., Carretier, E., Minassian, S., Benoit, L., & Moro, M. R. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113264. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264

Hamilton, J. L., Nesi, J., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2020). Teens and social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: Staying socially connected while physically distant. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5stx4.

Kar, S.K. and Arafat, S.Y., (2021). Digital self-harm in adolescents: Strategies of Prevention. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health-ISSN 0973-1342, 17(1), pp.137-141. doi:10.31234/osf.io/5stx4

Keles, B., Mccrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2019). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79-93. doi:10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Kokka, I., Mourikis, I., Nicolaides, N. C., Darviri, C., Chrousos, G. P., Kanaka-Gantenbein, C., & Bacopoulou, F. (2021). Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020760

Lee, J. (2020). Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 421. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30109-7

Muzi, S., Sansò, A., & Pace, C.S. (2021) What’s Happened to Italian Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Preliminary Study on Symptoms, Problematic Social Media Usage, and Attachment: Relationships and Differences With Pre-pandemic Peers. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.590543

Nearchou, F., Flinn, C., Niland, R., Subramaniam, S. S., & Hennessy, E. (2020). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: a systematic review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(22), 8479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052470 https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/5/2470/htm

Panchal, R., & 2020, A. (2020, August 21). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-COVID-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-COVID-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., Moreno, C., Parellada, M., Arango, C., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 1-27. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w

Patwardhan, I., Hurley, K. D., Thompson, R. W., Mason, W. A., & Ringle, J. L. (2017). Child maltreatment as a function of cumulative family risk: Findings from the intensive family preservation program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 92-99. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.010

Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., … & Snell, G. (2021). Mental health impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child and adolescent mental health. doi: 10.1111/camh.12501 https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12501

Sari, N. P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Jansen, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., & Riem, M. M. (2021). Higher Levels of Harsh Parenting During the COVID-19 Lockdown in the Netherlands. Child Maltreatment. doi: 10775595211024748

Stewart, C. (2020, April 01). Young people’s mental health during COVID-19 in the UK 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1108583/young-people-s-mental-health-during-COVID-19-in-the-uk/

Tang, S., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of affective disorders, 279, 353-360. doi: Teo AR, Choi H, Andrea SB, Valenstein M, Newsom JT, Dobscha SK, Zivin K. Does Mode of Contact with Different Types of Social Relationships Predict Depression in Older Adults? Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Oct;63(10):2014-22. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13667. Epub 2015 Oct 6. PMID: 26437566; PMCID: PMC5527991.10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

The Mental Health Fund. (n.d.). https://www.thementalhealthfund.org/

Wagner, K. D. (2020). Addressing the experience of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 81(3), 20ed13394. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20ed13394

Walter, K. (2020, June 3). COVID-19 Lockdown Having an Impact on Adolescent Mental Health. https://www.hcplive.com/view/COVID-19-lockdown-adolescent-mental-health

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/coronavirus-disease-(COVID-19)#:%7E:text=Coronavirus%20disease%20(COVID%2D19)

World Health Organization. (2020a, January 10). Coronavirus. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2020, September 28). Adolescent mental health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO. https://covid19.who.int/

Related Posts

The Public Health Crisis of Alzheimer’s Disease in African American and Hispanic Populations

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst...

Read MoreWhy Young Investigators Should Consider Prehospital Care Research

Figure 1: The author (14 hours and 10 patients into...

Read MoreInvestigating the Quality of Healthcare in Rural Areas

Cover Image: A rural Metro ambulance in Memphis, Tennessee. Rural...

Read MoreSeeing Double: A Look into Twin Types and Twin Studies

Figure 1: An image of the famous Olsen twins Source:...

Read MoreA New Perspective on Treating Asthma

Figure 1: This diagram displays the results of tissue remodeling...

Read MoreWhy Your Genes Might Impact Your COVID-19 Experience

Figure: An illustration of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. When it comes...

Read MoreJY