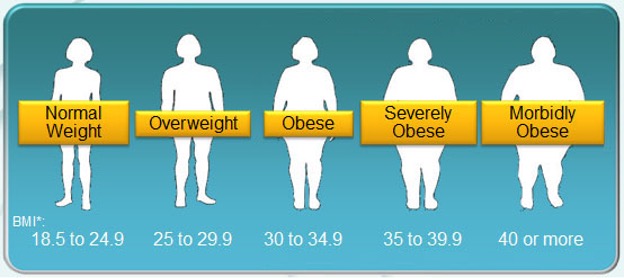

Figure 1: Obesity is typically diagnosed based on BMI. The different levels of obesity are shown here

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Introduction:

Obesity is one of America’s greatest public health concerns. For both children and adults, rates of obesity have generally been on the rise since 1980 (Hales et al., 2018). In 1980, 4.8% of men and 7.9% of women were obese; in 2008, those values had doubled to 9.8% and 13.8%, respectively (Carallo, 2011). More recently, as of 2018, about 42% of American adults were obese and as of 2016, about 18.5% of American children were obese (CDC, 2020; CDC, “Childhood Obesity Facts,” 2019).

It is well understood that obesity impairs both the mental and physical health; accordingly, obese individuals are estimated to have 30% more medical expenses than their non-obese counterparts. In 2006, obesity-related medical costs accounted for about 40% of the entire American healthcare budget. In addition, obesity causes significant drops in productivity – annually, obesity-related absenteeism in the workplace for each individual obese worker costs between $79 dollars and $132 dollars, accounting for billions of dollars of the total American economy (Çakmur, 2017). Given both the healthcare and productivity costs, it is clear that obesity presents a large economic burden on a national scale. And, with trends showing that obesity levels are only on the rise, it is crucial to understand the determinants for and risk factors of obesity in order to try to curb its growth.

From a medical standpoint, obesity is a serious issue. Individuals with obesity can have insulin resistance and are at higher risk for Type II diabetes (Barnes 2011). They are at risk for several cardiovascular conditions, including hypertension and coronary heart disease, and often have high cholesterol. They also often have respiratory complications and have lower vital and total lung capacity, along with the possibility of sleep apnea. Obese individuals have significantly higher chances of developing cancer and arthritis. Skin disorders, like intertrigo and eczema, are common. Furthermore, obese individuals are three times more likely to die prematurely than their non-obese peers (Ogunbode 2009).

On a biological level, the mechanism of obesity is not completely understood. Interestingly, however, it has become increasingly clear over the past years that obesity is not just a biological disorder. The growing prevalence of obesity is driven by external factors. In addition to health behaviors, there are clear disparities due to geography, socioeconomics, and race and ethnicity that are correlated with obesity. These make the obesity epidemic difficult to stop, as each factor is complex in its own way and requires different treatment by public health professional. This paper aims to comprehensively review both what is known about obesity from a medical perspective and each of the external factors; the hope is that a better understanding of the obesity crisis will allow public health experts to research and implement more nuanced solutions to the problem.

Obesity Overview:

There has been much debate within the scientific community about the classification of obesity given that it has determinants that are not solely biological. As such, many argue that obesity should be labeled as a behavioral abnormality. Nonetheless, many renowned medical foundations, including the American Medical Association, have chosen to classify obesity as a disease: as such, obesity refers to the condition where a person has a Body Mass Index (BMI) of over 30 (Stoner & Cornwall, 2014). The biological mechanisms underlying the accumulation of fat that characterizes obesity are still unknown. There are several proposed ideas, but two mechanisms seem to hold the most support.

The first of such mechanisms is genetic. Estimates vary, but various studies show that high BMI has between a 40% and 70% chance of being inherited. Both monogenic (characteristics arising from a single gene types) and polygenic (characteristics arising from multiple gene types) forms of obesity have been explored. On the monogenic side, researchers have been able to implicate mutations in leptin and melanocortin-4 receptor genes. Both play critical roles in energy homeostasis (which is further explored in the next paragraph); leptin is a hormone that inhibits hunger, and melanocortin-4 receptor binds several agonists, many of which also lead to hunger inhibition. On the polygenic side, several combinations of over 300 genetic loci have been marked as significant in resulting in obesity. Epigenomic research on obesity is ongoing and may reveal further genetic influences on obesity (Heymsfield & Wadden, 2017).

The second proposed idea is dysregulation in energy homeostasis mechanisms. Energy homeostasis refers to the balance of consumption and burning of calories. There are two main processes thought to be involved in energy homeostasis’s contribution to obesity, the first of which is sustained positive energy balance – this refers to a state in which a person is overconsuming calories while not expending enough for a long period of time. The second is resetting of the set point of body weight for a higher weight – for some reason, the body may choose to accept a higher weight as the “normal” body weight. This second process would explain why obese individuals cannot reduce their caloric intake easily and why even those who lose weight often regain it. The reasoning for this reset of weight set-point is not known currently and could be inherited or arise due to some biological or environmental trigger. A combination of both of energy processes would lead to a buildup of excess weight, and eventually to obesity (Schwartz et al., 2017).

Overall, it is clear that obesity onset is extremely complex and due to a variety of biological factors. More research into both genetic and energy-related reasons will elucidate more specific mechanisms underlying obesity in the future. However, the biological factors cannot be divorced from external determinants, including behavior, geographical location, and demographics.

Behavioral Drivers of Obesity:

Figure 2: Fast food is considered to be “energy dense.” Over the past several years, consumption of fast food has been on the rise, a possible contributor to rising obesity levels (Rennie et. al., 2005)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

There are a number of behavioral determinants related to obesity. Based on the effect that they have these determinants can be classified in two general categories: energy intake and energy expenditure. Energy intake refers to food and drink consumption. Despite the increase in obesity over the past few decades, there has not been an equal increase in overall caloric intake, suggesting that there instead have been differences to the types of food and drink being consumed. One significant change has been an increase in the amount of energy dense food being consumed. Energy dense foods are those that contain high levels of fats; fast foods and processed foods are generally energy dense (Rennie et. al., 2005). There has been an upward trend of consumption of fast food in the US over the past few years, and while studies are not conclusive, there is some evidence supporting an association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity (Rennie et. al., 2005; Poti et al., 2017). This increase in consumption may be related to the significant increase in the portion size of energy dense foods, including both fast foods and food items sold in discrete units, like prepackaged foods, snacks, and drinks, that has occurred over the past few decades (Livingstone & Pourshahidi, 2014). Concerningly, restaurant food is also more energy dense than homemade food. Both the increase in portion size and energy-density of the food consumed may contribute to rising obesity levels. (Rennie et. al., 2005).

Another area of interest is consumption of sugar-rich drinks, like sodas and juices. Over the past several years, there has been an upward trend in consumption of sugary drinks. Like with energy dense food consumption, the independent effects of sugary drinks on weight and obesity still needs to be explored (Rennie et. al., 2005). However, there is research that suggests that sugary drinks are associated with obesity and at the very least, discouragement of their consumption is important (Malik et al., 2006).

The second behavioral factor to study is energy expenditure. This refers to the amount of physical activity a person does to burn calories consumed. Over the past several decades, there has been a steady decrease in physical activity among the general American population, meaning less energy is being spent, contributing to the caloric imbalance caused by unhealthy eating behaviors (Rennie et. al., 2005; Browson et al., 2005). There are five main factors involved in this decline: leisure time, sedentary time, work-related physical activity, transportation-related physical activity, and general physical activity. There has been a slight increase in leisure time, which could potentially mean more time for exercise. However, this has been offset by the significant increase in sedentary time (time spent not doing physical activity). Additionally, there have been overall decreases to work-related physical activity, transportation-related physical activity, and general physical activity in the home – there are several reasons for this, including a general shift towards office jobs and away from physically taxing jobs (Browson et al., 2005).

Overall, a combination of increased energy intake and decreased energy expenditure has led to unhealthy caloric imbalances; these create the aforementioned dysfunctional biological regulation pathways.

Disparities in Obesity

In addition to behavioral factors, obesity-causing factors can be further stratified into different demographic groups, including geographic region, socioeconomic status, and race and ethnicity. By studying these groups, it becomes abundantly clear that there are several disparities in the American obesity landscape; additionally, however, when studying these groups it is critical to note that though discussed here in relative isolation, they are interconnected and their combined synergistic effects are what have resulted in obesity-related disparities.

Geographic Disparities:

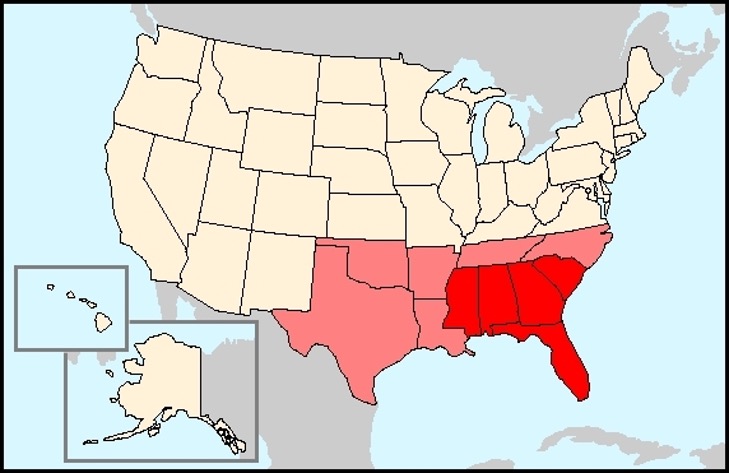

Figure 3: Obesity prevalence varies depending on region. The South (pictured in in light red), and particularly the Southeast (pictured in bright red), has disproportionately high levels of obesity as compared to the other regions in the US

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is clear that geographic region plays a significant role in determining risk for developing obesity. Generally, the West Cost and Northeast regions tend to have lower rates of obesity than the South, especially the Southeast (Wang & Beydoun, 2007). The comparison between the Midwest and the South is less clear – some studies have found that the Midwest has a lower rate of obesity than the South (Wang & Beydoun, 2007), while others have found the opposite (Sung & Etemadifar, 2019). Within these regions, there are clusters of high rates of obesity and low rates of obesity. These clusters vary per region, but there have been some trends between race and employment status. For some demographics, clusters have positive effects, meaning a disproportionately high number of individuals within the demographic group are obese. For others, clusters have negative effects, meaning a disproportionately low number of individuals within the demographic group are obese. In the South, clusters have a positive effect on Black populations. In the Northeast, there is a negative effect on Hispanic populations. In both the West and the Midwest, there is a positive effect on unemployed individuals; the reasons for why these relationships exist are still being explored (Myers et al., 2015). Across all regions, rural communities across the US generally have higher levels of obesity than urban communities; reasons may include transportation issues and lack of accessibility to healthy foods (Hill et al., 2014).

Socioeconomic Disparities

There is a clear relationship between socioeconomic status and obesity. Though obesity has risen among all demographic groups over the years, the prevalence of obesity amongst certain groups is disproportionately high. Generally, lower socioeconomic groups have higher obesity rates (Loring et al., 2014). For men in general, prevalence of obesity is similar across all income levels; however, for Mexican American and non-Hispanic Black men, obesity is generally more prevalent at higher incomes relative to those in lower income brackets. For women, obesity is generally more prevalent at lower incomes (CDC, “Obesity and Socioeconomic Status in Adults”, 2019). Studies have found that being under the poverty level, being unemployed, and receiving food stamps are strongly associated with obesity (Akil & Ahmad, 2011).

Racial & Ethnic Disparities:

Obesity prevalence is different among different racial and ethnic groups. Black and Hispanic Americans across the United States have a higher obesity incidence than White and Asian Americans (CDC, 2010). Obesity is also on the rise amongst Indigenous populations; this rise is of importance as traditional Western norms are often not aligned with Indigenous ways of living – thus, curbing obesity in Indigenous populations will potentially require a significantly different paradigm and set of public health guidelines (Bell et al., 2017). As discussed previously, as income increases, prevalence of obesity tends to decrease across all demographic groups; however, this protective effect is not as significant for Black individuals as it is for White individuals. Thus, even across different socioeconomic groups, obesity tends to disproportionately impact people of color (Assari, 2018).

Conclusions:

Obesity is one of the biggest public health threats the United States currently faces and also puts a significant burden on the American economy. The biological mechanisms of obesity are still being explored and may also be correlated to different external factors, including geography, socioeconomic status, and race and ethnicity. These factors all play a role in determining access to healthy food, job type, and healthcare, all of which may contribute to the onset of obesity. Thus, different populations have disproportionate levels of obesity. These diverse, unevenly weighted external factors, combined with inconclusive research regarding a particular individual’s independent risk factor for obesity, make the disease especially challenging to tackle on a national scale. Different racial, ethnic, income, and gender groups will need to be targeted by public health measures at the local level to curb the rise in dangerous obesity.

References

Akil, L., & Ahmad, H. A. (2011). Effects of socioeconomic factors on obesity rates in four southern states and Colorado. Ethnicity & Disease, 21(1), 58–62.

Assari, S. (2018). Family Income Reduces Risk of Obesity for White but Not Black Children. Children, 5(6), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060073

Barnes, A. S. (2011). The epidemic of obesity and diabetes: Trends and treatments. Texas Heart Institute Journal, 38(2), 142–144.

Bell, R., Smith, C., Hale, L., Kira, G., & Tumilty, S. (2017). Understanding obesity in the context of an Indigenous population—A qualitative study. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 11(5), 558–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2017.04.006

Brownson, R. C., Boehmer, T. K., & Luke, D. A. (2005). DECLINING RATES OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES: What Are the Contributors? Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437

Çakmur, H. (2017). Obesity as a Growing Public Health Problem. Adiposity – Epidemiology and Treatment Modalities. https://doi.org/10.5772/65718

Carallo, Kim. (2011, February 3). Worldwide Obesity Doubled Over Past Three Decades. ABC News. Retrieved January 22, 2021, from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/global-obesity-rates-doubled-1980/story?id=12833461

CDC. (2020, June 29). Obesity is a Common, Serious, and Costly Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

CDC (2019, June 10). Obesity and Socioeconomic Status in Adults: United States, 2005–2008. Centers for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db50.htm

CDC. (2019, June 24). Childhood Obesity Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html

Hales, C. M., Fryar, C. D., Carroll, M. D., Freedman, D. S., & Ogden, C. L. (2018). Trends in Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in US Youth and Adults by Sex and Age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA, 319(16), 1723. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.3060

Heymsfield, S. B., & Wadden, T. A. (2017). Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(3), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1514009

Hill, J. L., You, W., & Zoellner, J. M. (2014). Disparities in obesity among rural and urban residents in a health disparate region. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1051. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1051

Livingstone, M. B. E., & Pourshahidi, L. K. (2014). Portion Size and Obesity. Advances in Nutrition, 5(6), 829–834. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.114.007104

Loring, B., Robertson, A., Organisation mondiale de la santé, & Bureau régional de l’Europe. (2014). Obesity and inequities: Guidance for addressing inequities in overweight and obesity. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe.

Malik, V. S., Schulze, M. B., & Hu, F. B. (2006). Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 84(2), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.2.274

Myers, C. A., Slack, T., Martin, C. K., Broyles, S. T., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2015). Regional disparities in obesity prevalence in the United States: A spatial regime analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 23(2), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20963

Ogunbode, A. M., Fatiregun, A. A., & Ogunbode, O. O. (2009). Health risks of obesity. Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine, 7(2), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.4314/aipm.v7i2.64083

Poti, J. M., Braga, B., & Qin, B. (2017). Ultra-processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health—Processing or Nutrient Content? Current Obesity Reports, 6(4), 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0285-4

Rennie, K. L., Johnson, L., & Jebb, S. A. (2005). Behavioural determinants of obesity. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 19(3), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2005.04.003

Schwartz, M. W., Seeley, R. J., Zeltser, L. M., Drewnowski, A., Ravussin, E., Redman, L. M., & Leibel, R. L. (2017). Obesity Pathogenesis: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocrine Reviews, 38(4), 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00111

Stoner, L., & Cornwall, J. (2014). Did the American Medical Association make the correct decision classifying obesity as a disease? Australasian Medical Journal, 462–464. https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2014.2281

Sung, B., & Etemadifar, A. (2019). Multilevel Analysis of Socio-Demographic Disparities in Adulthood Obesity Across the United States Geographic Regions. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 10(3), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2019.10.3.04

Wang, Y., & Beydoun, M. A. (2007). The Obesity Epidemic in the United States Gender, Age, Socioeconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Epidemiologic Reviews, 29(1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxm007

Related Posts

UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Step in the Light Direction

Executive Board Advisor: Nishi Jain Co-Authors: Daniela Galvez-Cepeda, Katherine Faulkner,...

Read MorePreventing Peripheral Artery Disease in African Americans from Georgia: A Public Health Initiative

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2024...

Read MoreNeutrophils and their NETs

Figure: A neutrophil (yellow) ejecting a NET (green) to capture...

Read MoreAnahita Kodali