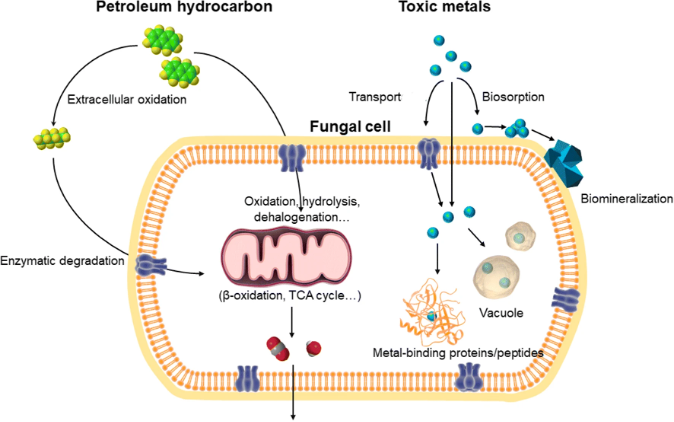

A diagram showing how a fungal cell combines with the hydrocarbon compounds in oil (Image Source: Li et al., CC BY 4.0)

Oil spillage has always been a major challenge to environmental health, especially in top oil producing countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and India. For instance, it has been shown that a 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico caused adrenal and pulmonary problems for marine animals (Wilkinson A. 2015). Furthermore, the effects of oil spills can persist for a long time in the environment. One team of researchers, after studying the Unalaska Island oil spill, discovered that smaller hydrocarbon compounds (alkane and polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon) were persistent in the region as much as 3.6 years after the spill. Not only were these small molecules found in the passive sampler device that was planted in the water, but also in the mussels that lived in that region (Carl et al., 2021). To combat the problem of oil contamination, scientists have employed several techniques to decontaminate regions of oil pollution. The most environmentally friendly technique is bioremediation, which involves the use of microbes to degrade hydrocarbon compounds in crude oil.

So far, the use of individual microbial isolates has been effective in degrading hydrocarbon compounds in contaminated soil and water bodies. Fungi, for example, are a unique and powerful biodegradable agent due to their catabolic enzymes, their ability to form mycelial networks, and their independence from pollutants as growth substrates (Harms et al,. 2011). However, the search is still on for the best microbe (or team of microbes) that can degrade all kinds of environmental pollutants at once.

To meet this challenge, researchers have opted for the use of ‘microbial consortia’ – teams of different microbes – for bioremediation instead of individual microbes (Sheldone et al., 2019).

To ascertain the efficiency of mixed microbial consortia, El-Aziz et al. (2021) isolated four fungal isolates from date palm soil: Alternaria alternate, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, and Trichoderma harzianum. Their experiment proved that using a mixed fungal consortium for biodegradation is more potent than using individual isolates alone.

El-Aziz and colleagues isolated four different species of fungi and tested if they are capable of degrading organic compounds individually using the DCPIP (2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol) method. In this method, three metrics are assessed to see which fungi are helpful for biodegradation: decolorization of the DCPIP, decrease in the amount of crude oil, and reproduction of the fungus. A fungal hyphae grown for one week was incubated in a conical flask containing DCPIP for 14 days at 30°C. After two weeks, the samples were evaluated using a spectrophotometer. The changing color of the reagent (DCPIP) from blue to colorless indicated the degrading ability of the fungi. The result showed that all the isolates could degrade crude oil, but to different degrees. The best isolates were A. flavus and T. harzianum, followed by T. terreus and A. alternata.

After this test, El-Aziz et al (2021) then attempted degrading the crude oil provided by Saudi Aramco, a Saudi Arabian oil company, using the four different isolates individually and then in various combinations (or consortia). The combinations were divided into four groups: the first group contained individual isolates, the second group contained two isolates, the third group contained three isolates, and the fourth group contained all four isolates. El-Aziz and his colleagues also evaluated the performance of the best fungal consortium on the biodegradation of normal alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

In comparison to the group with individual isolates, the consortia containing the mixed four fungal isolates at ratio 1:1:1:1 performed significantly better at degrading the crude oil, degrading it with an efficiency of 73.6% within 14 days. These findings demonstrate that mixed fungal consortiums are more potent than using individual fungal isolates and hold important implications for future oil cleanup efforts.

References

Sheldon Ramoutar, Azad Mohammed & Adesh Ramsubhag. (2019). Laboratory-scale bioremediation potential of single and consortia fungal isolates from two natural hydrocarbon seepages in Trinidad, West Indies, Bioremediation Journal, 23:3, 131-141, DOI: 10.1080/10889868.2019.1640181

Wilkinson, A. (2015). Deepwater Horizon oil spill linked to Gulf of Mexico dolphin deaths. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2015.17609

Harms, H., Schlosser, D. & Wick, L. (2011). Untapped potential: exploiting fungi in bioremediation of hazardous chemicals. Nat Rev Microbiol 9, 177–192 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2519

Carls MG, Larsen ML, Holland LG. (2015). Spilled oils: Static mixtures or dynamic weathering and bioavailability? PLoS ONE. 10(9): e0134448. pmid:26332909.

El-Aziz ARMA, Al-Othman MR, Hisham SM, Shehata SM. (2021). Evaluation of crude oil biodegradation using mixed fungal cultures. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0256376. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256376

Li Q, Liu J, Gadd GM. (2020). Fungal bioremediation of soil co-contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons and toxic metals. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 104: 8999-9008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10854-y

Related Posts

Study Finds Anthrax Toxin as Possible Substitute for Painkillers

Figure: A computer representation of the anthrax toxin protein (Source:...

Read MoreThe Geography of Disease: a Bayesian Approach to Epidemiology

Figure 1: A map showing relative rates of pancreatic cancer...

Read MoreTargeting crucial molecules used by coronaviruses to infect cells may lead to a broader antiviral treatment

Figure 1: Researchers have identified crucial molecules utilized by the...

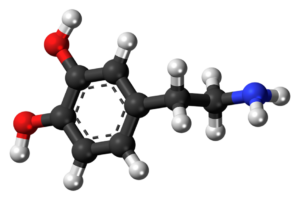

Read MoreLearned Control of Spontaneous Dopamine Impulses in Mice

Figure: Dopamine is the so-called “feel-good” neurotransmitter, involved in cognitive...

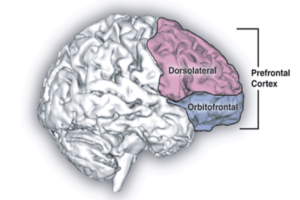

Read MoreStudy Reveals the Prefrontal Cortex is a Key Conductor in Sleep Regulation

Source: Laboratoires Servier, (CC BY-SA 3.0) Sleep is a fundamental...

Read MoreYour Personality Might Say Less About Your Brain, And More About Your Microbiome

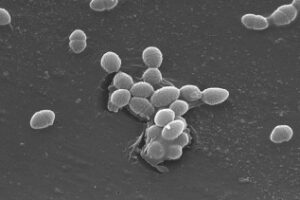

Figure 1: A scanning electron micrograph of Enterococcus faecalis, a bacterium...

Read MoreAsanga Patience