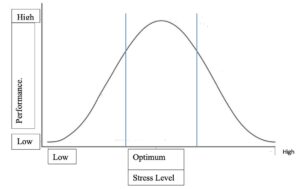

Figure: Assurance Game Payoffs. (Source: Author)

It is puzzling that an unpopular authoritarian regime, e.g., North Korea, is able to rule for a long time despite being way outnumbered by its opponents (Human Rights Watch, 2017). This paradox can be explained by thinking of rebellion as a collective action problem. While it is best for the group to rebel against the regime, it is not in an individual’s interest to do so, because he/she risks being punished severely by the dictator, who has every incentive to do so to deter other protestors. Given that an authoritarian regime can be so powerful, a second puzzle is how non-violent struggles can overthrow a ruthless regime. A notable successful example is the Indian struggle for independence from the British colonial power that had even used guns against unarmed civilians (the most well-known instance being the Jallianwala Bagh massacre). Beginning in the 1920s, the struggle was spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi, who strongly believed in non-violence (Ponnu, n.d.). Another important example is the Civil Rights Movement in the US. It is often associated with the reverend Martin Luther King Jr., who, influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals, emphasized the importance of a non-violent movement. Interestingly, Tina Rosenberg argues in her New York Times blog that “non-violent struggle is not just the moral choice; it is almost always the strategic choice” (Rosenberg, 2015). In this paper, I analyze resistance to an oppressive regime as an assurance game in the context of a collective action problem. The analysis shows that non-violence is strategically advantageous because it can get a large number of people to cooperate in resisting the regime together. However, its effectiveness in actually overthrowing the regime or uplifting its citizens out of oppression depends on a number of additional environmental factors.

The assurance game faced by two representative individuals, say A and B, under an oppressive regime can be described in terms of the following actions and payoffs (See Figure 1). Each individual can either cooperate with the other (i.e., join the rebellion) or defect (i.e., run away). Given that one player cooperates, the other’s best strategy is to cooperate because the payoff to cooperating is “best” as opposed to the payoff to defecting, which is “good.” Both individuals cooperating against a regime is the best outcome for both because it ensures that the rebellion succeeds, and the oppressive regime is overthrown. Given that A cooperates, if B chooses to defect, then B gets a good outcome. It is not as positive as the “best” outcome because B faces societal disapproval for running away, but it is better than the worst outcome which is to get punished by the dictator. Since each individual prefers “best” to “good,” cooperation by both is an equilibrium. That is, if one party cooperates, the other party finds it advantageous to cooperate too: the alternative gets them to a worse outcome. Cooperate-cooperate is a strategy where neither individual would want to change their action.

On the other hand, given that A defects, B would also rather defect because otherwise they risk the “worst” outcome of being punished. The payoff to B of defecting is “bad,” because that means that there will be no rebellion, and both have to continue to live under brutal oppression. It too is an equilibrium – given that the other side does not cooperate, it is better for one to defect too. This means that there are two equilibria in this game: either cooperate to fight against the regime or just live under oppression without doing anything about it. But one of the equilibria – both individuals cooperating – is better than the other. Although this assurance game is somewhat simplistic (for example – one’s decision to cooperate or defect in reality is going to be influenced by the size of the group that engages in rebellion, not just the decision of one other individual), it aptly characterizes the problem as that of shifting the equilibrium from no rebellion by anyone to one where all cooperate to join the rebellion. And strategic non-violent methods of protest can achieve this objective effectively.

Strategic non-violent resistance shifts the equilibrium from defect-defect to cooperate-cooperate in three ways: changing the payoffs, making the feeling of oppression a ‘common knowledge,’ and increasing trust that counterparts will cooperate as well. First, a non-violent resistance changes the payoffs in this game by making the worst outcome (being one of the few to be punished by the dictator) slightly better. This is because the method of these protests leaves very little room for the dictator to punish the rebels (Rosenberg, 2015). A violent protester who sets a vehicle on fire can be punished more severely than a person who just decides to march from one end of a city to another. A historical example would be the Montgomery Bus Boycott following Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat for a white passenger in the city of Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. No one could be prosecuted for boycotting buses, which increased the support for the boycott. The protests effectively avoided prosecution of their members, while inflicting heavy losses on the bus company’s finances.

Second, the protests are strategically designed to attract media and public attention so that the common knowledge of the unpopular nature of the regime increases. These protests attract media limelight because they are mostly symbolic in nature, and about things that matter to people. An interesting example is the Salt March in India in 1930 (Andrews, n.d.). The Salt March was chosen to break a British law that taxed salt and barred any Indian from producing it. Among all laws, why did Mahatma Gandhi choose this one to break? In fact, many of the other Indian leaders thought it was too inconsequential. After all, it had been enacted fifty years before. Mahatma Gandhi, however, was clear that an item such as salt, of daily use in every household, rich or poor, would resonate more than an abstract demand for greater political rights (“Dandi March- Why Mahatma Gandhi Broke the Salt Law to Commence the Civil Disobedience Movement?,” 2018). Also, marching 240 miles on foot to go to the ocean and extract salt with his own bare hands was a symbolic act that helped drum up popular support all along the way. Indeed, this movement was the talk of the entire world: it was featured daily in the New York Times for many days, and on the front page for two consecutive days (Dalton, 2012).

Third, strategically non-violent protests feature leaders who are able to showcase themselves as being selfless, moral, and just. The leader’s actions build trust among their fellow protesters that they will not betray the cause. The fellow protesters reciprocate the trust by being trustworthy themselves. It is said that Mahatma Gandhi used to preach only after he practiced his sayings. Al Gore’s book “Earth in the Balance” narrates a story that Gandhi took two weeks to tell a boy to give up sugar for the sake of his health, because he practiced it himself before delivering the advice (Gore, 1992). Martin Luther King Jr. even survived an attempted assassination, but never backed down from his non-violent methods, building the trust in people’s minds that he was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for the movement to succeed and stick to his ideals come what may.

Since non-violent protests are able to stir the masses, they impact their oppressive regimes in some ways that violent protests cannot. First, the regime is viewed negatively in international circles – in other countries that are generally not at risk of oppression by the regime and able to comment critically or even take responsive action. For the international audience, quelling a protest by force is less justified in the case of peaceful ones than violent ones. For example, China’s brutal suppression of the Tiananmen Square protest induced more international criticism, and even arms embargoes, than did the British actions against the Irish Republican Army (Watts, 2005). Second, non-violent protests are able to arouse sympathy and empathy among people within the regime itself, who would otherwise not have supported the movement. For example, the Civil Rights Movement in the US was able to win over the support of many white Americans (Thompson, 2013).

Although non-violent movements inspire the cooperation of many, and often succeed in their objectives, this is not always the case. The non-violent Tiananmen Square protest did not achieve its objective (Yu, 2019). Conversely, there are some instances where armed action has worked. The American War of Independence and the Vietnam war are such examples. Another caveat about non-violent movements is that they cannot guarantee immediate success: they sometimes take generations to achieve results. For example, the non-violent part of the Indian struggle for independence began in the late 1800s and ended as late as 1947, when India finally gained independence. The Civil Rights Movement in America, too, took place over decades and although it was able to partially fulfill its immediate objectives, full racial equality is elusive even today, as seen from the Black Lives Matter protests. Therefore, the effectiveness of non-violence in overthrowing the regime or obtaining full rights depends on the situation. One theory does not fit all collective action problems involving resistance to oppressive regimes – but it does offer a helpful model for starting to understand the problem and considering how new or existing social movements can be launched and improved.

In summary, while non-violence may not always achieve results, and certainly not quickly, it does have its advantages in securing widespread cooperation against a brutal regime. Using an assurance game framework, we can see how it increases the chances of cooperation by reducing the costs to protestors, spreading awareness of injustices, and increasing trust. Also, it can win international support and internal sympathy. Indeed, non-violence is not only moral but also strategic.

References

Andrews, E. (n.d.). When Gandhi’s Salt March Rattled British Colonial Rule. HISTORY. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.history.com/news/gandhi-salt-march-india-british-colonial-rule

Civil Rights Movement Timeline. (n.d.). HISTORY. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.history.com/topics/civil-rights-movement/civil-rights-movement-timeline

Dalton, D. (2012). Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action. Columbia University Press.

Dandi March- Why Mahatma Gandhi broke the salt law to commence the civil disobedience movement? (2018, March 12). India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/dandi-march-why-mahatma-gandhi-broke-the-salt-law-to-commence-the-civil-disobedience-movement-1187528-2018-03-12

Gore, A. (1992). Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the Human Spirit. Rodale Books.

Human Rights Watch. (2017). North Korea: Events of 2017. In World Report 2018. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/north-korea

Ponnu, R. (n.d.). Ahimsa: Its theory and practice in Gandhism | Peace, Nonviolence & Conflict Resolution. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/ahimsa-Its-theory-and-practice-in-Gandhism.html

Rosenberg, T. (2015, February 13). How to Topple a Dictator (Peacefully). New York Times. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/13/a-military-manual-for-nonviolent-war/?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=7EFB718CC5A537B5A0DE8DB486B7F946&gwt=pay&assetType=PAYWALL

Thompson, K. (2013, August 25). In March on Washington, white activists were largely overlooked but strategically essential. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/in-march-on-washington-white-activists-were-largely-overlooked-but-strategically-essential/2013/08/25/f2738c2a-eb27-11e2-8023-b7f07811d98e_story.html

Watts, J. (2005, May 11). Tiananmen inmates linked to EU arms embargo. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/may/12/china.jonathanwatts

Yu, V. (2019, May 31). Tiananmen square anniversary: what sparked the protests in China in 1989? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/31/tiananmen-square-anniversary-what-sparked-the-protests-in-china-in-1989

Related Posts

Universality of the Face: New Research Points to a Shared Human Commonality in Emotional Expression

Figure 1: Examples of emotional expressions Source: Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels Raising...

Read MoreWho gets the Golden Ticket? Navigating the Murky Waters of COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation

Figure 1: The race for a vaccine is in fully...

Read MoreAlleviating Vaccine Hesitancy: The Path to a Safer Future

The human mind is constantly working on the fly, adapting...

Read MoreIncarceration and Motherhood: A Brief Overview of Maternal Health Issues in American Prisons

Figure 1: Guards in prisons are able to put prisoners...

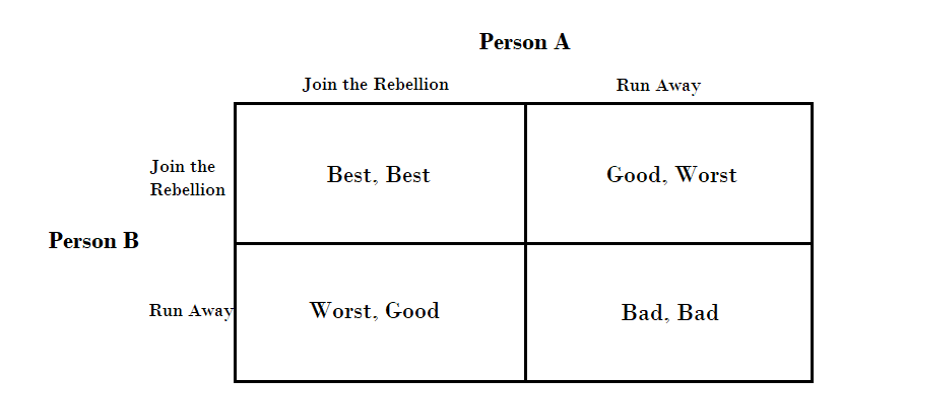

Read MoreRetitling Stress: A Look at the Yerkes-Dodson Law

Figure 1: This graph compares stress level with performance at...

Read MoreCaribbean History through Genetics and Archaeology

Figure 1: A map of the Caribbean Islands from 1894...

Read MoreAnusha Kallapur