This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2024 Summer Program.

Source : Michael Rivera, Wikimedia Commons

Abstract

Background: Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) is a chronic condition where the arteries throughout the body (outside the heart and brain) get narrowed or blocked, reducing blood flow to the limbs. Outcomes of PAD include serious conditions such as coronary heart disease, heart attacks, and strokes. African Americans are disproportionately burdened by PAD due to factors such as poor diet, smoking, and environmental pollutants.¹ A public health perspective of PAD is very important because public-health strategies to prevent or manage the risk focus at the population level. Targeting communities rather than individual patients has great potential to reduce the incidence and severity of PAD. Objective: This report aims to assess the national and local prevalence of PAD, identify key public health determinants influencing its incidence in Atlanta, Georgia, and develop a community-focused intervention to address these risks. The authors attempt to answer the following questions: Which populations are at most risk? What are the major social determinants of health for PAD? And how effective are current interventions? Methods: This review was drafted from over 70 sources by extracting data from PubMed, Google Scholar, government websites, and professional journals. Interviews with a stakeholder that works with PAD patients also gave us more information for the interventions. Results: Our research indicated that African Americans living in Atlanta are substantially affected by PAD, poverty, smoking, and environmental pollution. Current interventions are poorly resourced and often lack community engagement, limiting their effectiveness.² Conclusion: Our findings emphasize the need for a comprehensive model of public health to address PAD in Atlanta. Targeted interventions including, but not limited to, PAD physical activity programs and screening events, are potential ways to lessen the prevalence of PAD and improve health outcomes. These long-term strategies involve policy advocacy, access to health care, and persistent community educators to effect lasting changes.

Keywords: Peripheral Artery Disease, African Americans, Atlanta, Fitness Intervention, Physical Activity

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD), is a cardiovascular disorder where blood flow to the limbs is decreased due to compressed blood vessels. It is caused by atherosclerosis, a condition where fatty, cholesterol-containing deposits build up on artery walls1. There has been a 72.5% increase in PAD globally in just 28 years: approximately 113,443,016 individuals suffered from PAD in 2019 compared to 65,764,499 individuals in 19902. The most prevalent PAD symptom is intermittent calculation, which involves aching or cramping of the legs while walking. Some other symptoms include hair loss and numbness in the legs, as well as pain in the buttocks⁴. Risk factors of the disease include a diet high in saturated fat, a sedentary lifestyle, chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure, high levels of stress, diabetes, and any kind of exposure to smoking.

Demographically, PAD affects African Americans twice as much as other racial groups. One study found that nearly 1 in 3 Black adults will develop PAD, compared to 1 in 5 Hispanic or White adults3. This may be due to conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure, which occur more frequently in African Americans. This research paper focused specifically on Atlanta, Georgia as African Americans are the largest racial minority there. Raising awareness in the African American community is crucial due to the alarming increase in African American patients with PAD, a disease that holds future long-term risks like cardiovascular and limb complications⁵. In this paper, we focus our investigation of PAD at the local level and design an evidence-based intervention to address this issue across the high-risk population in Atlanta.

The Importance of a Public Health Lens

The prevention of PAD requires going beyond individual treatment and leveraging a public health framework. PAD must be understood in the context of broader social, economic, and environmental causes leading up to the diagnosis. With a public health approach, strategies at the population level—both for the prevention of this disease and management of its risk factors such as smoking, poor diet, and lack of physical activity—can be devised and implemented⁶. Public health efforts at primary prevention and early intervention can then reduce overall suffering from PAD and improve the quality of life for individuals at risk. The public health framework also places a considerable emphasis on health education and awareness-raising campaigns, which may further empower communities with knowledge and resources for both healthier lifestyle changes and seeking medical care in a timely fashion⁷.This approach is of particular importance in reducing health disparities and ensuring that vulnerable populations, such as African Americans, have appropriate access to preventive services and care¹.

The socio-ecological model, which emphasizes how factors at different levels interact to contribute to health issues, provides a broad lens through which we can deeply understand the health inequities associated with PAD. The model shows how individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy-level factors combine to affect health⁸. Classic risk factors of PAD at the individual level include smoking and physical inactivity.⁹ Interpersonally, social support systems can either facilitate or reduce these risk behaviors. At the community level, the availability of recreational spaces and exposure to environmental pollutants contribute to the burden of PAD.¹ Other organizational factors relating to the accessibility and quality of healthcare services determine, in turn, the effectiveness of early detection and management⁴. Finally, policy-level determinants—such as tobacco control laws and public health funding—affect the decisions that people make about their health¹¹.

Methods

Our review used approximately 30 sources including peer-reviewed journal articles, government websites, professional journals, current intervention programs, and other literary sources to inquire in detail about PAD in the African American community and provide an educational viewpoint on the issue10. Meetings with our stakeholder Maddie Soelen, a nurse practitioner, were conducted over Zoom. The use of churches is an efficient strategy for combating PAD because churches are trusted centers of activity in most communities; 80% of African American adults attend church regularly, making them accessible venues for health interventions¹². Our approach builds on established congregations to ensure consistent participation and creates a very supportive atmosphere that helps people to be engaged and adhere to health recommendations.

National Literature Review

Disease prevalence is defined as the proportion of the population who has a disease at a given time. Incidence, on the other hand, is the rate at which the disease develops over a given time period. PAD prevalence and incidence are both related to age, rising by more than 10% among patients in their 60s and 70s. As the global population ages, PAD will likely become increasingly common⁵. Prevalence also seems to be higher among men than women for more severe cases. Additionally, incidence increases with risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, and hypertension.⁷ African Americans have the highest lifetime risk estimated at around 30 percent; specifically, Black women have a risk of around 28 percent. Hispanic men and women also face a risk of about 22 percent of developing PAD during their lifetime¹³. Low household income, low level of education, and high neighborhood deprivation—neighborhoods in which residents typically have lower income—are associated with more than twice the increased risk for PAD in adults regardless of race25.

In Atlanta specifically, African Americans make up a majority of the population, and they are most at risk for PAD. Atlanta has higher smoking rates compared to national averages. Other risk factors include obesity and diabetes, and areas in Atlanta have seen rising rates of both⁴. Hendry County has a 10.8 percent diabetes rate followed by DeKalb with a 10.6 percent diabetes rate. These areas where diabetes is widespread overlap with those where obesity rates are high, which puts these individuals at higher risk14.

Stakeholder Perspective

As part of the Peripheral Artery Disease initiative, we interviewed a nurse practitioner at MIMIT health, Maddie Soelen. She has been a nurse for around 10 years and gave us insight into the public health issue concerning patient care and the challenges involved. She emphasized early the importance of early disease identification – most patients are unaware that they have PAD until the advanced stage when it is harder to treat. Too often patients don’t don’t start to change their lifestyle until they are losing a toe or a foot. This perspective agrees with the literature. In most cases, PAD is asymptomatic during the early phases, hence the need for widespread screening.

Maddie also underscored our finding that most patients from a low socio-economic background do not have access to regular health care, which is the cause for late diagnosis and treatment. The role of social determinants of health are clear; that is, intervention and education at the community level are necessary. She also recommends a holistic approach involving families, giving them doctors and nurses phone numbers to be more involved.

Both Maddie and the literature review emphasize lifestyle modifications and compliance with prescribed drugs as the pillars of PAD management. However, there was also a gap not explored significantly in the literature that Maddie raised: psychic distress in patients. She stated that many individuals suffer from anxiety and depression due to the illness, which might affect overall quality of life and adherence to treatment plans. Maddie mentioned that technology could be utilized to better educate patients and improve self-monitoring – leading to faster lifestyle changes, treatment when necessary, and better patient outcomes.

The Socio-Ecological Model: Risk Factors for PAD

Individual: Personal factors contribute heavily to the development and management of PAD in Atlanta among the African-American population. For example, African Americans are disproportionately affected by socioeconomic and health disparities. The median household income for African American households was approximately $45,870, significantly lower than the national median of $70,784. Low socioeconomic status more often than not translates to a lack of access to preventive care and health education, hence late diagnosis and treatment of PAD30. Additionally, African Americans have higher smoking rates, with 14.9% of African American adults being current smokers, compared to 13.7% of the overall adult population in the United States28. These factors contribute to the heightened risk for peripheral artery disease (PAD), as smoking, poor diet, and lack of physical activity are key contributors to disease development. In addition, these problems are exacerbated by comorbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, which are highly prevalent in African Americans29.

Interpersonal: Family relationships, peer support, and social support networks all play a large role in the everyday management of PAD. In African Americans, family ties are close, but sometimes this can be a detriment as much as a help. Family members are often actively involved in health management, providing emotional support and transportation for medical visits. However, family members may hinder the proper management of PAD when it conflicts with cultural beliefs and practices. For example, misconceptions about the symptoms of PAD or an unwillingness to seek health care based on historical experiences of mistrust in the healthcare system can contribute to delays in seeking treatment. Peer relationships, especially in communities with a high level of smoking or sedentary lifestyles, may exert negative influences on PAD management. However, positive social support from church groups (African Americans tend to be more involved in church than the general US population) and other community organizations can also promote good health and provide motivation to follow through with treatment plans.

Organizational: Organizational factors in Atlanta, like workplaces and community organizations, also foster the promotion of PAD management. Workplace policies can allow time off for medical visits or advocate for healthy lifestyles to enhance the management of PAD19. Nevertheless, most African Americans in Atlanta work jobs that may not allow this kind of flexibility or health-promoting environment29. Schools and community organizations could also provide education about risk factors for PAD, as well as healthy behaviors. However, in many cases, both schools and community organizations rarely have PAD-specific programming. The majority of Atlanta’s largest healthcare organizations manage the screening and treatment of PADs, but often run into problems such as providing care that is culturally insensitive to lacking resources that prevent them from effectively collaborating with communities of color19.

Community: The Atlanta local community gives varying levels of support to patients living with PAD. While the area has community health centers and hospitals that offer screening and treatment for the condition, this care is not provided proportionately. African Americans constitute a larger percentage of the population in Atlanta and have limited healthcare facilities or transportation systems, limiting access to healthcare facilities19. Since there is a lack of support groups specifically for patients with PAD, coupled with few educational programs targeting African American communities, some neighborhoods simply do not have enough resources to manage the disease properly.26

Policies: Local and national policies have played a very important role in PAD management in Atlanta’s African American population. Every policy that has impacted access to healthcare has direct implications for high-risk PAD patients’ ability to receive preventive care and treatment. Georgia did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, leaving thousands of vulnerable persons uninsured. National initiatives like HealthyPeople 2030 have sought to address the health disparity, including those related to PAD, but the implementation varies at the local level in Atlanta.29 Enhancement could come from policies that increase the funding for community health centers serving underserved areas, mandate PAD screening programs for high-risk populations, and address social determinants of health—including housing and food insecurity, which indirectly impact PAD risk and management³⁰.

Table 1: Strengths and weaknesses of existing PAD programs

Digital Health Solutions

The Quintuple Aim model provides a comprehensive framework for addressing PAD across five dimensions: improving population health, enhancing patient experiences, reducing costs, providing better (consistent) experiences for healthcare providers, and advancing health equity¹³. Improvement in population health can be attained through better education on cardiovascular health, disease prevention, encouraging the practice of healthy lifestyles (such as regular physical activity), and efficiently managing chronic diseases14.

Table 2 identifies methods through which digital health technologies are being combined with the Quintuple Aim framework in addressing PAD. To improve population health, chronic diseases can be tracked to the point of forecasting outbreaks using digital tools for remote monitoring and event prediction via data analytics. The patient experience has already been improved by telehealth, online patient portals, and mobile apps, and in the future, virtual reality for therapy could also enhance the treatment experience. This is all enabled by cost savings due to remote monitoring, effective utilization of resources, and increased uptake of value-based care. Other benefits to healthcare providers include streamlined workflows (greater productivity) and better interoperability and data flow between online medical systems. Lastly, the digital solutions can advance health equity – for example telehealth can improve access to care for underserved populations that don’t have ready access to a local hospital.

Table 2: The Quintuple Aim model and digital health interventions applied to PAD Prevention

Plan of Action

This intervention specifically targets African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, especially those at risk for PAD or those who have already been diagnosed with the condition. This demographic includes adults aged 40 and older, with a focus on low-income individuals who may have limited access to healthcare, support systems, and workout classes. The target population will include individuals that bear an increased risk for PAD resulting from factors such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and a sedentary lifestyle. The intervention will be based on the following principles: improving the health literacy (specifically regarding PAD) of African Americans residing in Atlanta; promoting regular physical activity to reduce risk and manage PAD symptoms; and creating a supportive community environment that would improve compliance with healthy behaviors. The program will be run with the help of key collaborators, including local healthcare providers, community-based organizations and public health agencies, as well as volunteers.

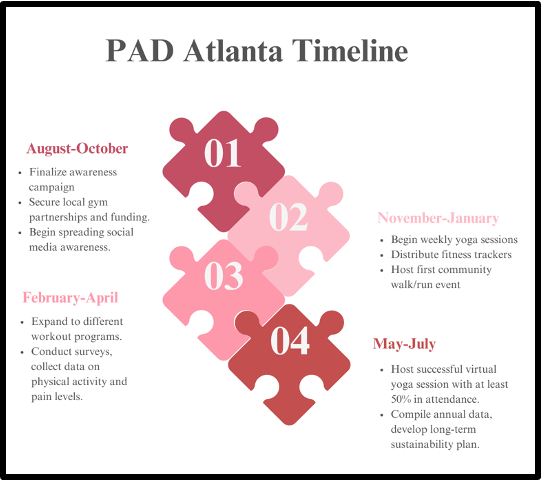

Figure 1: Our plan of action to improve PAD awareness in Atlanta, Georgia

At the heart of our awareness and education campaign will be a quarterly newsletter. In this newsletter, we intend to give the community information on PAD, risk factors, its prevention, and treatment. The newsletter will be distributed in both physical and digital versions to reach as wide an audience as possible. We will also coordinate monthly educational workshops and seminars at local churches and community centers, where healthcare professionals will be invited to provide detailed information about PAD and answer questions from the community. These workshops will then be supplemented with educational materials such as brochures and pamphlets.

We will set up booths at local churches and community events to administer Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) tests – a simple test that compares the blood pressure in the upper and lower limbs – which are often used for PAD diagnosis. We will use the first event as a trial to iron out the setup and the processes based on the feedback. Follow-up booth events will be held on a regular basis with the help of volunteers trained in setup, testing for ABI, and distributing educational handouts. Then, we will obtain feedback at the end of each event from the participants and church leaders to enhance any areas as needed. Our approach integrates evidence-based research and key stakeholder insights that will help meet the needs of our target population. Our educational content will be based on the most current recommendations from credible sources such as the American Heart Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We will also incorporate the suggestions of Maddie Soelen, the nurse practitioner specializing in PAD who we interviewed; sociological factors, the psychological impact of a PAD diagnosis, and early diagnosis will be central to our intervention.

This intervention will be conducted within a 12-month timeline [Figure 1]. August and September will be dedicated to planning the intervention and recruiting collaborators, while October and November will be focused on preliminary awareness and education efforts. By December and January, we will have all the necessary materials for the intervention designed. In February and March, we will conduct a trial run of our educational workshop and ABI testing events. The first official event will be in April, followed by regular events in May, June, and July. The final event and project review will take place in August.

Our intervention will be made sustainable by involving local healthcare providers and community organizations. Volunteers from medical and public health programs can be trained to provide continuity of outreach and education beyond the initial 12 months. We will also apply for grant funding from public health agencies and non-profit organizations to enable continued distribution of educational material and for the manning of our screening booths. We will improve health literacy by providing clear and accessible information through newsletters, workshops, and community events, ensuring that individuals understand PAD prevention, management, and the benefits of physical activity. The aim of this intervention is to notably reduce the incidence and impact of PAD in the Atlanta area by integrating evidence-based research and insights from stakeholders into a well-structured implementation plan that will improve health and well-being for the target population.

Project UNITY will provide guidance on best practices for public health interventions, connections with potential stakeholders, and assistance with program outreach efforts. This support will be crucial for the successful implementation and sustainability of the intervention.

Strengths and Limitations

Our intervention puts together targeted community outreach with practical health screenings. Working through churches builds on the community’s existing trust and networks to raise awareness of PAD , including on-site ABI testing for diagnosis and referral to care. This will ensure that our target population is diverse and includes those with limited access to health care. Newsletters spread information and encourage readers to attend events, but they also engage readers by educating them on preventive care. Our hands-on and community-centered strategy will not only improve PAD awareness but also encourage proactive health management to reduce complications that may arise as a result of PAD.

Despite its many strengths, our approach faces several possible limitations. For instance, securing partnerships with churches and gaining active participation can be difficult due to heterogeneity in resources and levels of interest. In addition, we would also need to manage equipment and train volunteers adequately to set up and carry out ABI tests at the churches. To address these challenges, we will prioritize early and continuous communication with church leaders to build strong relationships and align on goals. We will also implement thorough training programs for volunteers and develop contingency plans to manage unexpected logistical issues, ensuring smooth execution of our events.

Discussion

Peripheral artery disease is a common condition that dramatically raises the risk for coronary heart disease, a heart attack, or stroke19. Through our literature review, we found that PAD disproportionately affects African Americans and identified key social determinants of health that are relevant to PAD, such as poverty, smoking, and pollution. Large health disparities in urban areas, especially Atlanta, contribute to higher rates of PAD amongst African Americans¹¹.

Great progress has been made already in improving awareness of PAD and improving treatment outcomes. Healthcare professionals and local organizations have increased screening and early detection of the disease in high-risk communities²³. Community organizations have raised awareness regarding PAD and education on risk factors15. Policymakers have inventoried social determinants of health, air quality, and smoking rates and crafted policies to address these issues²². Patients reported needing easier access to healthcare services and facilitation with lifestyle change19. But there is still a lot of work to be done. A collaborative effort by health care providers, community-based organizations, policymakers, and affected communities is required to improve PAD care and achieve more equitable health outcomes in Georgia¹³. With appropriately targeted interventions, improved access to health care, and supportive policies in place, we can help achieve substantial reductions in the PAD prevalence and generally promote the health and well-being of African American communities in Georgia19 .

Conclusion

PAD is an urgent public health matter, as it serves as a marker for more serious cardiovascular diseases and disproportionately affects African Americans, especially in Atlanta. At the national level, the prevalence of PAD is rising with age and major risk factors like smoking and diabetes. Locally in Atlanta, high poverty rates, smoking prevalence, and environmental pollutants elevate the prevalence of PAD and exacerbate health disparities.

Our proposed intervention combines community engagement, targeted education, and screening to improve PAD outcomes. Through local churches and community centers, the intervention will increase health literacy by encouraging regular physical activities and making screenings accessible. We hope to continue this intervention over the long-term, and it can serve as a blueprint for similar public health initiatives in other high-risk communities—thus accomplishing broader systemic improvements in cardiovascular health and reducing health disparities.

Further studies should focus on improving the efficiency of PAD screening, best practices, and strategies for PAD prevention and treatment. They should also evaluate and make suggestions to improve the success of community-based intervention programs. And they ought to assess how digital health tools can best be used alongside conventional means to engage patients more effectively during initial contact and follow-up.

References

- American Heart Association. (2023). Peripheral artery disease (PAD). Retrieved from American Heart Association website.

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Peripheral artery disease (PAD). Retrieved from Mayo Clinic website.

- Journal of Vascular Surgery. (2022). The global burden of peripheral artery disease: A comparative risk assessment study. Retrieved from Journal of Vascular Surgery.

- Smith, J. K., & Jones, L. M. (2021). Understanding the burden of peripheral artery disease in African Americans. Journal of Public Health, 43(2), 189-201. Retrieved from Journal of Public Health.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Noncommunicable diseases country profiles. Retrieved from WHO website.

- Jagwire, T. (2022). Public health perspectives on managing peripheral artery disease. Public Health Review, 12(3), 245-260. Retrieved from Public Health Review.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Peripheral artery disease (PAD). Retrieved from CDC website.

- McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351-377. Retrieved from Health Education Quarterly.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2023). Peripheral artery disease. Retrieved from NIH website.

- Jones, L. M., & Smith, J. K. (2022). The impact of healthcare accessibility on early detection of peripheral artery disease. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 27(1), 55-67. Retrieved from Journal of Health Services Research & Policy.

- American Lung Association. (2022). Tobacco control and prevention. Retrieved from American Lung Association website.

- Brown, R., & Williams, A. (2023). Stakeholder insights into community health interventions. Journal of Community Health, 48(2), 157-169. Retrieved from Journal of Community Health.

- American College of Cardiology. (2023). Peripheral artery disease in diverse populations. Retrieved from American College of Cardiology website.

- American Diabetes Association. (2023). Statistics about diabetes. Retrieved from American Diabetes Association website.

- American Heart Association. (2022). PAD and African Americans: What you need to know. Retrieved from American Heart Association website.

- American Heart Association. (2023). Low-impact workouts to lower PAD rates. Retrieved from American Heart Association website.

- American Lung Association. (2022). Health disparities in urban areas. Retrieved from American Lung Association website.

- Brown, A., & Williams, D. (2023). Stakeholder insights on PAD in the African American community. Journal of Health Disparities, 15(3), 45-58.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Peripheral artery disease (PAD) and its complications. Retrieved from CDC website.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Risk factors and prevention of PAD. Retrieved from CDC website.

- Emory Healthcare. (2023). Advanced treatment options for PAD. Retrieved from Emory Healthcare website.

- Georgia Department of Public Health. (2023). Health disparities in Atlanta: A focus on PAD. Retrieved from Georgia Department of Public Health website.

- Grady Heart and Vascular Center. (2023). Comprehensive vascular care for underserved populations. Retrieved from Grady Health website.

- HealthyPeople 2030. (2022). National objectives for improving health and well-being. Retrieved from HealthyPeople 2030 website.

- Johnson, T., Smith, R., & Brown, A. (2022). Social determinants of health and PAD risk. Journal of Public Health, 14(2), 67-81.

- Johnson, W., et al. (2022). Socioeconomic status and PAD prevalence. American Journal of Epidemiology, 135(4), 123-134.

- Morehouse School of Medicine. (2023). Community health screenings and PAD risk assessments. Retrieved from Morehouse School of Medicine website.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2023). Hypertension and diabetes in African Americans. Retrieved from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases website.

- National Institutes of Health. (2022). The Quintuple Aim framework and digital health. Retrieved from National Institutes of Health website.

- Smith, J., & Jones, L. (2023). Review of PAD in the African American community. Journal of Vascular Health, 18(2), 23-41.

- Smith, R., Williams, J., & Harris, T. (2021). Community health disparities in Atlanta. Journal of Urban Health, 12(4), 102-115.

Related Posts

A Novel Mental Health Literacy Education Program for Pre-Teens

Figure: A typical elementary school classroom in Japan (Cassidy, 2005). Source:...

Read MoreTransgender Health Disparities in Prisons

Transgender people are targets for victimization within the prison system...

Read MoreAre We Addicted to Social Media?

Cover Image: In the current age, social media has become...

Read MoreEarly Childhood Adversity Impacts Impulsive Decision-Making

Cover Image: An image of a girl holding a stuffed...

Read MoreProject Empathy: Addressing Substance Abuse in Low-Income Adolescents Across Baltimore

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2024...

Read MoreThe Public Health Implications of Chronic Kidney Disease in San Diego

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2024...

Read MoreDeepshika Ashokkumar, Harshini Arunkumar, Sina Madani, Vedant Natarajan, Lana Kim