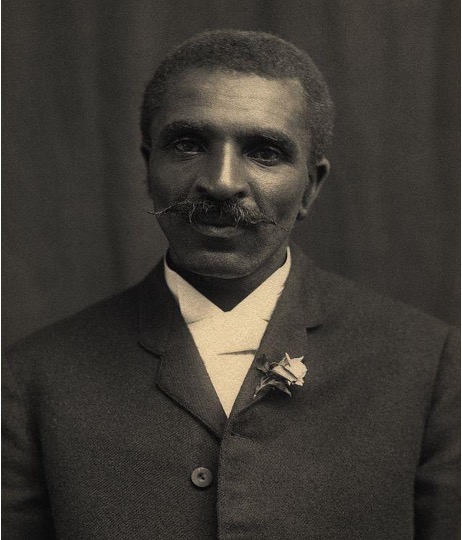

Figure 1: George Washington Carver: “The Peanut Man” (Photograph ca. 1910)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

George Washington Carver is one of the most famous agricultural scientists and inventors in world history. Carver’s bust in Diamond, Missouri, the town of his birth, is an official national monument. Only two other Americans had their birthplaces so designated: George Washington and Abraham Lincoln (Mackintosh, 1976).

Carver was born in the American South at the end of the American Civil War in 1864, the year before slavery was outlawed by the 13th amendment to the US constitution. After a mix of early educational experiences, he earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the Iowa Agricultural College at Ames in 1894. While getting a master’s degree at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, he began his research in microbiology that made him a scientific legend. Carver was raising a small number of Spanish peanuts at the Tuskegee Experiment Station in 1903, his earliest recorded involvement with the plant (Mackintosh,1976).

Carver realized that years of growing cotton had depleted the nutrients from the soil and by growing nitrogen-fixing plants like peanuts, the soil could be restored. This idea helped poor southern farmers to heal spent soil and extend their yield. He emphasized the cultivation of peanuts in a 1916 bulletin “How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption.” During the next four years, Carver conducted further research with the peanut: in 1919, he wrote the Peanut Product Corporation of Birmingham about a milk substitute he had just produced from the plant. This invention piqued the interest of several peanut-processing firms in his work. The United Peanut Associations of America invited Carver to speak at their 1920 convention. He discussed “The Possibilities of the Peanut” and exhibited 145 more peanut products. In January of 1921, Carver testified in front of the United States Congress with his presentation about peanuts numerous times, which marked the beginning of his fame as a public figure. Carver was affectionately dubbed “The Peanut Man” (Mackintosh, 1976).

But Carver wasn’t just about peanuts. He further suggested hat farmers use other nitrogen-fixing plants like soybeans and sweet potatoes to replenish the soil and offered 100 ways to use sweet potatoes in production too (“Ex-slave aids paralytics”, 1937).

Carver’s work became especially relevant after boll weevil attacks on Southern cotton crops. The boll weevil contributed to the economic woes of Southern farmers in the 1920s, and the situation was exacerbated by the Great Depression in the 1930s. This forced farmers to replace the cotton crop as a whole (Childers, 1932). Carver was active in suggesting crop alternatives, and further invented plenty of new products made out of peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes, such as milks and flours, that we still use today. All of these could be raised by farmers as a replacement for cotton and sold for a profit.

George Washington Carver once said that his work was “the key to unlocking the golden door of freedom to our people” (T. A. M’Neal, 1935). He undoubtedly reached his goal: through his groundbreaking achievements in agriculture,Carver both improved the economic conditions of African Americans in the South and paved the way for greater African-American representation in science.

References

(1942). Carver to Work for Ford. New York Times

Childers, J. S. (1932). A Boy Who Was Traded for a Horse. American Magazine

Mackintosh, B. (n.d.) George Washington Carver: The Making of a Myth. The Journal of Southern History, 507-528

McMurry, L.E. (2004). George Washington Carver: The Life of the Great American Agriculturalist. Powerplus

McMurry, L.O. (1982). George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol. Oxford University Press

M’Neal, T. A. (1935). An interview with Carver.

Related Posts

Why Do We Really Need Vitamins?

Figure 1: This figure illustrates the interaction between an enzyme,...

Read MoreHidden Cell-Based HIV Reservoirs Found via Sugar Signatures

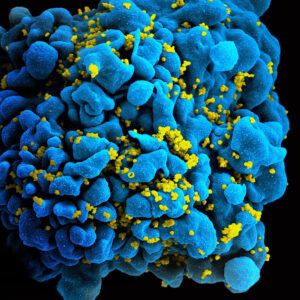

Figure 1: SEM image of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)...

Read MoreCaribbean History through Genetics and Archaeology

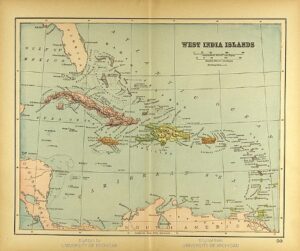

Figure 1: A map of the Caribbean Islands from 1894...

Read MoreMilena Pugina