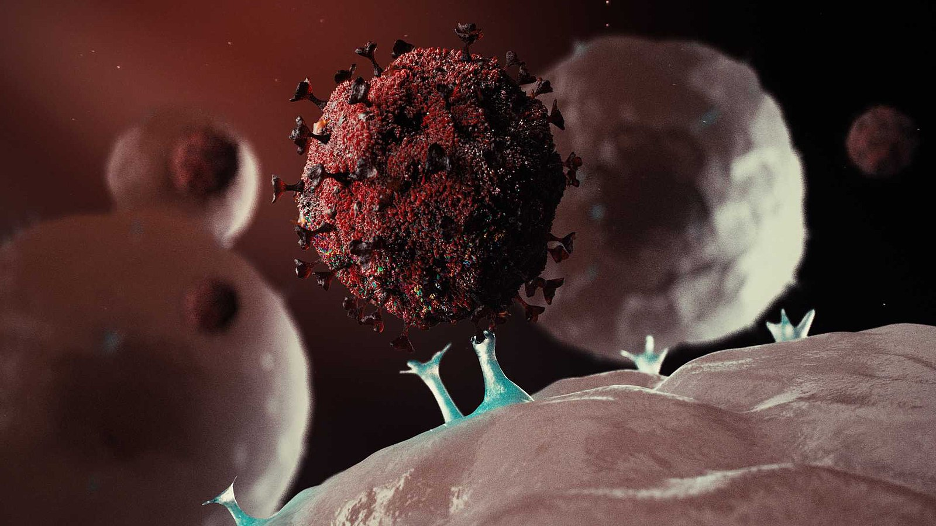

Figure: An illustration of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. When it comes to SARS-CoV-2 infections, a new study suggests that genetics may play a role in both susceptibility and severity. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Author: We Are Covert Ltd)

In the past, genome-wide association studies have found correlations between specific forms of certain genes and individual susceptibility to infectious diseases such as hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis, dengue, malaria, and HIV-1 (Chapman & Hill, 2012). The latest disease to join this group is COVID-19, which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for the current pandemic. In a recent study, 13 genetic variants have been connected to either an increased risk of infection or an increased degree of illness severity in regard to SARS-CoV-2 (Saey, 2021). The discovery of these genetic variants brings scientists one step closer to understanding the risk factors for contracting COVID-19. This finding is especially useful since patient variations in age, gender, and body mass index have failed to fully account for patterns of disease severity across infected individuals (COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, 2021).

Before discussing the study results in more detail, it is important to clarify how DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is organized in the body. DNA strands are not found loose in cell nuclei. Instead, proteins bind to each DNA molecule, condensing and protecting it. The resulting structure, consisting of a single DNA molecule and bound proteins, is called a chromosome, and the physical locations of specific genes on a chromosome are known as loci. Overall, the study determined that of the 13 loci connected to an increased risk of COVID-19 infection or an increased degree of illness severity, 9 were tied to the severity of infection following the onset of COVID-19 without showing a significant correlation with SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. The locus with the strongest association with COVID-19 severity was 3p21.31 (COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, 2021). This study confirmed a previous finding that variations at the ABO locus were tied to SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility (for example, type-O blood was associated with a decreased risk of infection) and additionally identified a locus in the 3p21.31 area with a stronger correlation with susceptibility than severity (Saey, 2021).

The present study also examined lifestyle factors like BMI, relying on the nearly 100 BMI-associated genetic variants identified to date in order to evaluate BMI genetic risk. Smoking was found to correlate with higher hospitalization rates, while genetically predicted higher BMI was associated with both a higher likelihood of hospitalization and increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is key to acknowledge that for both genetic and lifestyle factors, correlation does not constitute causation. For instance, the study also identified a puzzling association between higher genetically predicted height and increased susceptibility (COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, 2021).

This is not to say that all genetic variants were associated with negative consequences for individuals’ health. For instance, genetically predicted elevated red blood cell count was tied to decreased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, 2021). Previous studies have identified other health advantages to genetic variants as well. A base-pair deletion in the tail of the HIV coreceptor CCR5, for example, is associated with a slower progression of AIDS in heterozygous individuals (with one copy of the gene possessing the base-pair deletion, and one normal copy), as well as a decrease in HIV-1 susceptibility in homozygous individuals with two altered copies of the gene (Chapman & Hill, 2012).

Overall, the identification of single-gene defects and their repercussions for SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and severity could help answer two of the most perplexing questions of the pandemic: why is COVID-19 capable of such devastation in otherwise healthy patients, and why do patients of comparable health have COVID-19 experiences ranging from extended hospitalization to a total lack of visible symptoms? While the study of single-gene defects is a start, it by no means provides a full explanation to address these vital questions. The majority of disease-associated variants are tied to very small increases in susceptibility/severity risk. Because gene defects tend to cluster on related immune pathways, it is likely that heritability of infectious disease susceptibility and severity results from multiple gene variants (Chapman & Hill, 2012). The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (2021) used some control groups who were unaware of their SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 status, failing to account for potential asymptomatic cases or infections late in the study. Future studies might incorporate more rigorous testing of control groups – yet another reason to lay focus on increasingly fast and accurate SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 testing.

References

Chapman, S. J., & Hill, A. V. S. (2012). Human genetic susceptibility to infectious disease. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(3), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3114

COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. (2021). Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03767-x

Saey, T. H. (2021, July 8). How your DNA may affect whether you get COVID-19 or become gravely ill. Science News. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-covid-how-dna-genetic-risk-infection-severe-illness

Related Posts

Dopamine Deficiency and Its Effects on Addiction

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

Read MoreNew Study Finds that Media Multitasking Impairs Memory in Young Adults

Figure 1: Engaging with multiple types of digital media simultaneously,...

Read MoreWhat Drives Musical Pleasure? Scientists Now Have the Name

Figure 1: Why is music so rewarding for the human...

Read MoreThe Brain and Sign Language — Evidence of a Universal Language Center?

Figure 1: The English alphabet and numbers 1-9 as signed...

Read MoreCould This Be the First Drug to Slow the Progression of Alzheimer’s?

Figure 1: A cross section of a model brain Source: unsplash.com...

Read MoreCaroline Conway