This article was originally submitted to the Modern MD competition hosted by the Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science (DUJS) and was recognized as an honorable mention.

Introduction:

To serve their patients most equitably, medical practitioners need to understand how gender should help determine the care and treatment which people receive. Oftentimes, conditions present differently depending on gender. With a male bias in the recognition of symptoms, women often go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, missing the treatment they deserve and require. This holds especially true in diagnosing autism spectrum disorder, or ASD.

The term ASD encompasses a host of disorders falling along the autism spectrum. These range from autistic disorder to Asperger syndrome to pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, with ASD now the single category defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, DSM-5 (Hyman et al., 2019). ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by issues with social interaction and communication, along with repetitive behaviors and hyper focus. The severity of ASD fluctuates widely on an individual basis (Wood-Downie et al., 2020).

ASD manifests differently and more discreetly in females than males, especially those who are high-functioning, making it even more challenging to diagnose (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019). This is problematic, as females with ASD are misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, and diagnosed at later ages, resulting in them not obtaining the support and intervention they need to manage their autism. This causes a variety of detrimental effects to the well-being of these women, in both their mental and physical health. In fact, an often-cited comparison estimates that there is one woman to every four men with ASD, with women being diagnosed later (Fombonne, 2009). The profile of ASD must be expanded and updated to include the female autistic phenotype. Doing so will increase the number of diagnosed women, thus improving their quality of life by instilling in them self-compassion and understanding, while increasing self-determinism.

Causes:

The principal issue behind the underdiagnosis of ASD females is the widespread misunderstanding of how ASD is displayed by females. This misunderstanding stems from a variety of factors, one of which is the higher rates at which females with ASD partake in camouflaging behaviors.

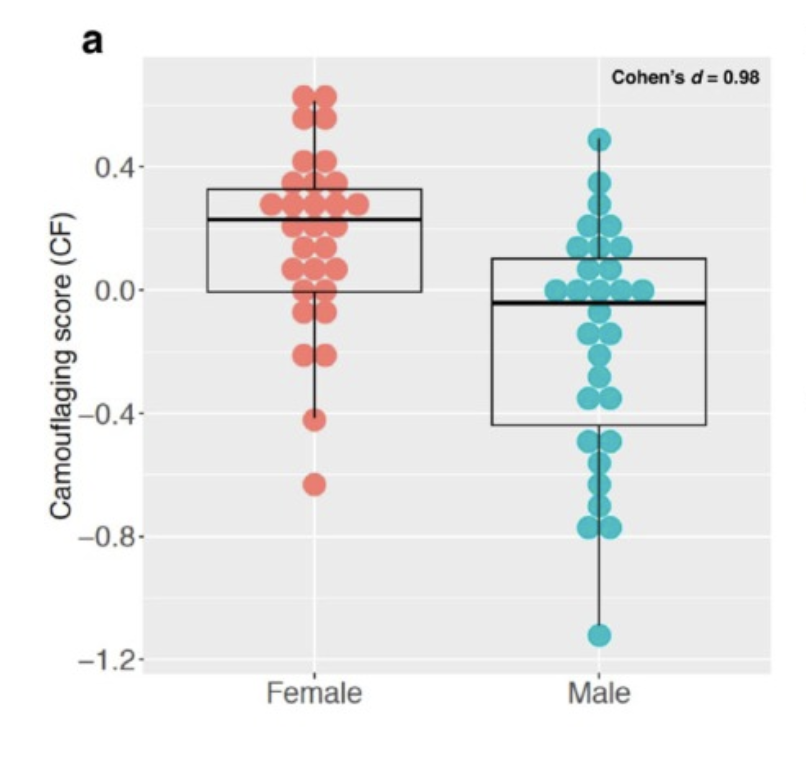

Camouflaging is a tactic utilized to hide or lessen perceived social limitations and appear more neurotypical (Willey, 1999). Such camouflaging practices include forcing eye contact during discussions, speaking with prepared phrases or jokes, mirroring others’ actions, and mimicking facial expressions or gestures. Several studies have operationalized camouflaging in an attempt to quantify the difference in camouflaging levels between genders. In one study, women with autism scored substantially higher (p<0.001) than ASD men as marked by a measurement that notes the degree of camouflaging, or CF score, as seen in figure 1 (Lai et al., 2016).

Figure 1: Lai et al., found in their 2016 study that women with ASD were far more capable than ADD men of camouflaging behavior. (Source: Lai et al., 2016, CC BY 4.0)

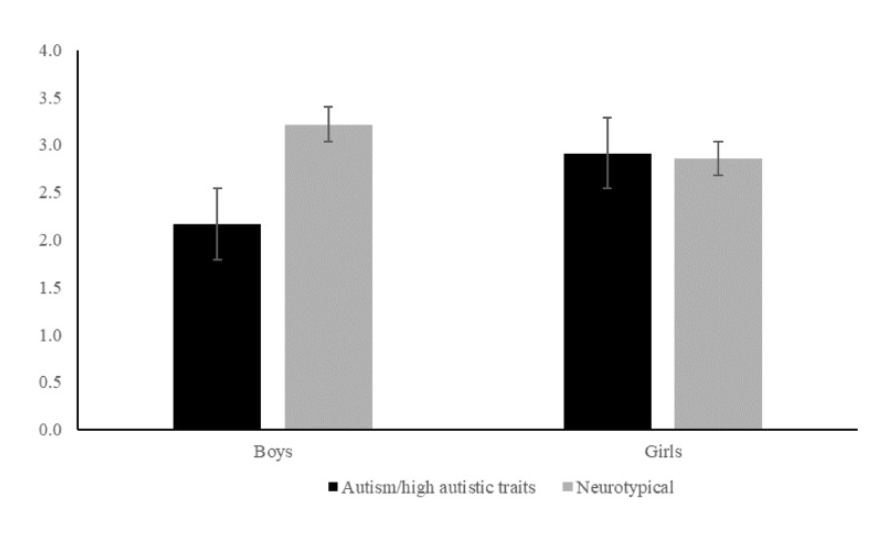

Other researchers determined that, by measuring camouflaging among both neurotypical and ASD females and males, ASD females are more similar to neurotypical females in terms of social reciprocity than ASD males and neurotypical males. This occurred despite those females with ASD demonstrating similar levels of autistic traits. An Interactive Drawing Test (IDT), an unstructured interaction in which a researcher and participant take turns to develop a drawing, was administered to gauge levels of social reciprocity, and girls with autism had much higher IDT scores than their male counterparts, as reflected in figure 2 (Wood-Downie et al., 2020).

Figure 2. The 2020 study conducted by Wood-Downie et al. found that girls with autism had much higher scores on an interactive-drawing test (IDT) than males, indicating that they are similar to non-autistic females in their capacity for social reciprocity. The Y-axis lists IDT scores, while the X-axis describes gender and whether or not the child has ASD. (Wood-Downie et al., 2020, CC BY 4.0)

As shown in figures 1 and 2, autistic females are more apt than males to hide their social shortcomings through camouflaging behaviors, making it so they don’t necessarily present traditional ASD characteristics. This contributes to clinicians’ failure to spot ASD in females: ASD females are more skilled at masking their social difficulties.

The underdiagnosis of the ASD female also arises from the limitations of ASD diagnostic assessments. The criteria of many diagnostic assessments are centered on research on ASD males and do not include the unique female autistic phenotype. Popular diagnostic instruments, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Autism Diagnosis Interview-Revised, and the Social Communication Questionnaire are not sensitive enough to catch autistic tendencies in females, as their research was conducted with a largely male subject pool (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019). This failure to document the unique female ASD symptomatology in diagnostic assessments has made it so females must display more severe autistic symptoms and greater cognitive and behavioral issues to be identified with ASD (Russell et al., 2010; Dworzynski et al., 2012). Thus, many high-functioning women don’t receive an ASD diagnosis.

Societal and cultural expectations and conceptions also fuel the misunderstanding surrounding the presentation of autistic traits in females. Gender stereotypes may be conducive to camouflaging because females with ASD may be told to “act like a woman/girl,” which tends to translate to: be more socially active (Lai et al., 2016). Furthermore, females may face a greater stigma for being disruptive, abrasive, or less empathic, all of which are stereotyped as more masculine traits (Goldman, 2013). Behaviors that may be concerning when seen in a boy, such as shyness or passivity, may be overlooked when displayed by autistic females, as these are thought to be more feminine characteristics (Geelhand et al., 2019). Society’s standards and gender expectations are a disservice to females with ASD. These cultural norms may spur unnatural camouflaging behaviors in ASD girls and cause parents, teachers, and clinicians to be dismissive of females presenting autistic tendencies.

Effects:

During their youth, ASD females specifically are at high risk for a host of mental health issues, including anxiety disorder, depression, increased thoughts and/or attempts at suicide, and eating disorders (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019). Among women with ASD, recurrent depressive disorder is most commonly diagnosed (50% of patients), though some authors imply the symptoms of bipolar affective disorders are just as, if not more, frequent (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019). A study aimed at recording the experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism also measured women’s anxiety levels. The average Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety score of this sample was 13.5, which is higher than the recommended clinical cut-off, or clinically significant score, of 8 (Bargiela et al., 2016). Although ASD in females is correlated with high occurrences of poor mental health, a timely diagnosis can diffuse the challenges ASD women face throughout their lifetimes (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019).

Along with negative impacts on mental health, women with autism are susceptible to sexual abuse and rape due to their social vulnerabilities and naivete (Rynkiewicz et al., 2019). In a qualitative study researching the lives of females diagnosed with ASD later in life, 9 out of 14 participants reported sexual abuse, most of which occurred in relationships (Bargiela et al., 2016). These women reported struggling to track a man’s intentions, meaning they had trouble discerning if he was acting friendly or making unwanted sexual advances (Bargiela et al., 2016). Additionally, ASD women described isolation and rejection as teenagers, resulting in an inability to compare tips for safety with female peers and leaving them desperate for acceptance (Bargiela et al., 2016). One woman shared “Because we don’t sense danger and can’t. That’s one reason, I think you not reading people to be able to tell if they’re being creepy, you’re that desperate for friends and relationships that if someone is showing an interest in you, you kind of go with it and tend not to learn from others’ safety skills.” (Bargiela et al., 2016). ASD women need a diagnosis to gain insight into their potential for sexual abuse and to learn necessary preventative strategies.

A less quantifiable, but still poignantly important negative effect of underdiagnosing ASD in females is that these women often suffer from self-loathing, as they are unable to understand their differences and particular needs. One qualitative study interviewed late-diagnosed females with ASD to investigate their shared experiences. Women’s failed attempts at connection resulted in thoughts that they were “wrong,” “broken,” or “bad” (Leedham at al., 2019). Some found camouflaging to be extremely draining and dissatisfying. One woman relays, “… it started at school and it went on to college as well … [I wore] different clothes to everything that I wore at home … I hated this person that I put on” (Leedham at al., 2019). There were a number of common threads that ran through these women’s recollections after being diagnosed with ASD – many talked about a hidden condition, the process of acceptance, post diagnosis impact of others, and acceptance of their new identity on the autism spectrum, as seen in table 1 (Leedham., 2019).

Table 1: Common themes from a qualitative study of 11 female adults who had received an ASD diagnosis at or over the age of 40 years. (Leedha, 2019, Table re-produced by author)

Both this study and another of similar nature described how participants felt great sadness and regret from not receiving a diagnosis early in life, coupled with a sense that delayed diagnosis had been harmful to their education and well-being (Bargiela et al., 2016). One woman summarized, “anyone who’s got to middle age with undiagnosed autism has had to basically do Olympic level training in how to be a normal person … [when I] appear sort of normal, that is because of the years of actual effort that I’ve put into it” (Leedham et al., 2019).

Solutions:

Early intervention plays a key role in lessening the negative impacts of being a female with ASD, by nurturing coping mechanisms, self-compassion, and self-understanding. To properly identify more females on the autistic spectrum at early ages, more research must be undertaken to specifically determine the parameters of the female autistic phenotype. Such research can utilize digital programs to remove human biases from influencing outcomes. One study deployed the EyesWeb software platform and Kinect sensor to digitally code the gestures of autistic children during two activities of the ADOS-2 (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition, n.d.) to properly track the children’s gestures without the interference and manipulation of human judgement (Rynkiewicz et al., 2016). The sensors tracked the fervor with which children gesticulated by measuring the length of their gestures, with this data being automatically computerized (Rynkiewicz et al., 2016). Ultimately, the study deduced that girls with autism, on average, gestured more vividly than boys with autism (Rynkiewicz et al., 2016).

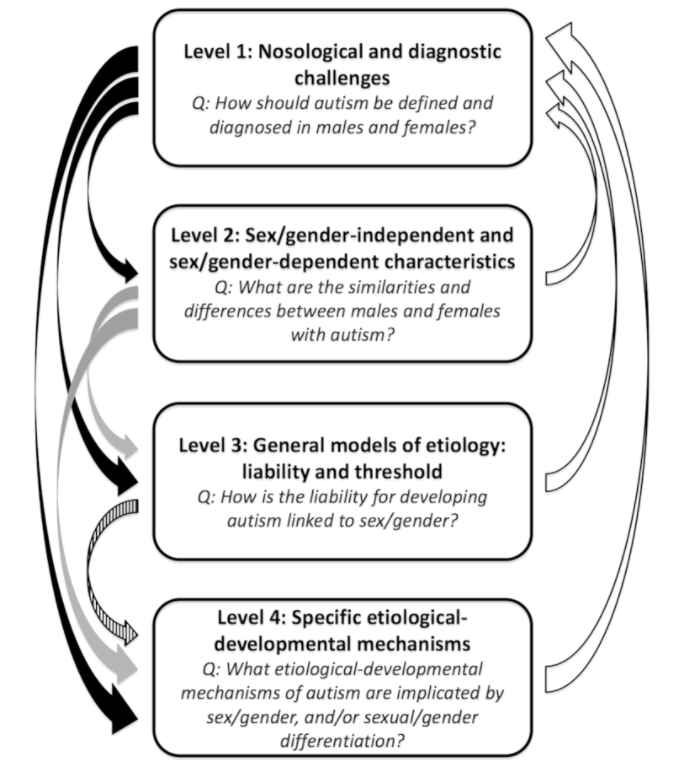

This study is an ideal model of how future research can be done; it examined a key disparity between the female and male autistic phenotype objectively, without the bias of human perspective. Research covering the autistic phenotype is extensive and diverse, and it often proves complicated to find linkages between various research themes. One paper proposed a conceptual framework that categorized research into four levels, each of which answers a particular question. Research found in one level correlates and feeds into research done at later levels, providing an intertwined body of data for future research, as seen in figure 3 (Lai et al., 2015).

Figure 3: A conceptual framework that organizes ASD research into four discrete and connected levels, each associated with a key question. (Source: Lai et al., 2015, CC BY 3.0)

Following this framework would make tracking commonalities between studies more intuitive, allowing findings to build off each other and making break-throughs more feasible. Once such research into the autistic phenotype by gender is performed and outcomes agreed upon, diagnostic methodology, such as the DSM-5, must be updated to reflect the new female ASD profile.

Broader characterizations of the autistic phenotype to include females and the education of clinicians on the unique female autistic phenotype are also needed to successfully recognize more ASD women. Currently, there is a widespread misunderstanding on what it means to be an autistic female throughout the medical community. This causes doctors not to recognize ASD in women presenting with milder and varying symptoms. Qualitative studies of late diagnosed autistic women noted that participants often felt that their experiences weren’t grasped by professionals (Leedham et al., 2019). Misconceptions that those with ASD all demonstrate acute social and communication difficulties compounded professionals’ hesitancy to diagnose females who had some social proficiency (Bargiela et al., 2016). An ASD woman described, “When I mentioned the possibility to my psychiatric nurse she actually laughed at me…I asked my mum, who was a GP at the time…if she thought I was autistic. She said, ‘Of course not’.” (Bargiela et al., 2016). Professionals also misattributed women’s struggles to other disorders (Bargiela et al., 2016). As one ASD woman said, “Four to five years of depression and anxiety treatment…years of talking therapy…and not once did anyone suggest I had anything other than depression” (Bargiela et al., 2016). Even if diagnostic instruments are changed to encompass the female autistic phenotype, little progress will occur until health care professionals are educated on female ASD presentation and their biases and misconceptions challenged.

Finally, society’s expectations for both girls and those with ASD need to be reevaluated. A variety of individuals, from teachers to parents, must understand that ASD does not just involve total social incapacity and that symptoms present themselves along a spectrum. Additionally, behaviors that may elicit concern in parents for boys, such as shyness and passivity, also need to be noted and taken into consideration when observed in girls. Parents, teachers, and clinicians need to possess the same extent of knowledge and vigilance for girls with ASD as they do for autistic boys.

Conclusion:

With a ratio of four men to one woman diagnosed with ASD, autistic women are misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, and diagnosed much later than their male counterparts. This results in them not obtaining the treatment they deserve (Fombonne, 2009). Women with ASD are underdiagnosed in large part due to misunderstanding of their autistic phenotype. ASD women camouflage their social troubles more than autistic men. ASD diagnostic tools have been engineered around research of mainly ASD males, and social and cultural expectations are responsible for both camouflaging behaviors and the inability to flag autistic traits. The underdiagnosis and late diagnosis of ASD females has a myriad of negative effects. These span from a high risk of a host of mental health disorders, to a greater possibility of sexual abuse and rape, to poor self-worth and understanding. To ensure that no woman’s ASD goes undetected and untreated, research must be done to expand the autistic phenotype to include the unique female ASD symptomatology. In addition, medical professionals must be educated on the different presentation of autism in girls. Finally, society at large needs to reassess its implicit biases and stereotypes involving both women and ASD. One study explained that after diagnosis, women felt a sense of “vindication,” “eureka,” and understanding of their life experiences and needs. When describing her life post-diagnosis, an ASD woman given the pseudonym of Lily shared in an interview, “I feel free, very much more free.” (Leedham et al., 2019).

References

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

Dworzynski, K., Ronald, A., Bolton, P., & Happé, F. (2012). How Different Are Girls and Boys Above and Below the Diagnostic Threshold for Autism Spectrum Disorders? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(8), 788–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.018

Fombonne, E. (2009). Epidemiology of Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Pediatric Research, 65(6), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1203/pdr.0b013e31819e7203

Geelhand, P., Bernard, P., Klein, O., van Tiel, B., & Kissine, M. (2019). The role of gender in the perception of autism symptom severity and future behavioral development. Molecular Autism, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0266-4

Goldman, S. (2013). Opinion: Sex, gender and the diagnosis of autism—A biosocial view of the male preponderance. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(6), 675–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.006

Hyman, S. L., Levy, S. E., & Myers, S. M. (2019). Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 145(1), e20193447. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3447

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/Gender Differences and Autism: Setting the Scene for Future Research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Ruigrok, A. N., Chakrabarti, B., Auyeung, B., Szatmari, P., Happé, F., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2016). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism, 21(6), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671012

Leedham, A., Thompson, A. R., Smith, R., & Freeth, M. (2019). “I was exhausted trying to figure it out”: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism, 24(1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319853442

Russell, G., Ford, T., Steer, C., & Golding, J. (2010). Identification of children with the

same level of impairment as children on the autistic spectrum, and analysis of their service use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(6), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02233.x

Rynkiewicz, A., Janas-Kozik, M., & Słopień, A. (2019). Girls and women with autism. Psychiatria Polska, 53(4), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.12740/pp/onlinefirst/95098

Rynkiewicz, A., Schuller, B., Marchi, E., Piana, S., Camurri, A., Lassalle, A., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2016). An investigation of the “female camouflage effect” in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-016-0073-0

Willey LH. (1999) Pretending to Be Normal: Living with Asperger’s Syndrome. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Wood-Downie, H., Wong, B., Kovshoff, H., Mandy, W., Hull, L., & Hadwin, J. A. (2020). Sex/Gender Differences in Camouflaging in Children and Adolescents with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(4), 1353–1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z

Related Posts

Rethinking ‘Junk’ DNA: The Vital Role DNA Repeats Play in Cancer and Aging

Figure: The image above, created by the National Institutes of...

Read MoreData Analysis of Global Covid Vaccination (7 March to 4 April 2022)

Figure: In this map, the color shows the sum of...

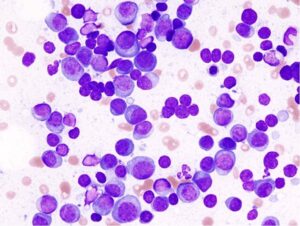

Read MoreAnti-SLAMF7 Treatment for Multiple Myeloma by the Elimination of Immunosuppressive T Cells

Figure 1: Smear preparation of bone marrow from a patient...

Read MoreWhite Noise Can Improve Memory, Boost Attention, and Reduce Stress

Source: Ivan Samkov Music has evolved over the years, with...

Read MoreHow the Plague Changed Our Genes

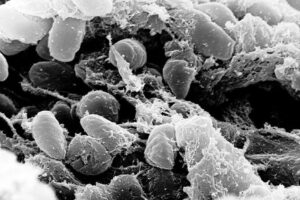

Figure 1: An image of the Yersinia pestis bacterium that caused...

Read MoreTo safeguard Africa’s topmost predators

From Nepal’s bengal tiger to Kenya’s big Lions, conservation of...

Read MoreLillian Graham