Figure: Two cheetahs lie side by side. As the fastest land animal, the cheetah was of particular interest in a recent study that produced a mathematical model predicting the maximum running speed of any given animal. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, safaritravelplus)

Cheetahs, sloths, humans — whatever the animal, a new study proposed a mathematical model to calculate its maximum running speed, determining whether the animal in question could match highway speeds or would lose a race to a turtle. Based on the factors that go into the model’s calculation, the researchers have found that some animals truly are just built for speed. An animal’s slenderness, leg length, number of legs, and spinal mobility all influence its capacity for speed (University of Cologne, 2021). Most important, perhaps, is an animal’s mass, which most of the other factors scale with (Günther et al., 2021). Maximum running speed tends to increase with animal mass, but only up to 50 kg (the average weight of a cheetah); beyond this, animals lose speed due to their size. Elephants, for instance, are relatively slow despite their long legs because their bones must be heavy enough to support their weight. Also, an increase in muscle size causes an increase in the time required for muscle contraction at maximum speed (University of Cologne, 2021). All of these elements contribute to one great balancing act between propulsive leg force/inertia and air drag, which increases with running speed (Günther et al., 2021).

Human sprinters max out their speed at around 45 kilometers per hour, roughly matching a sprinting domestic cat. Unlike quadrupedal mammals like the cheetah, humans lack the ability to gallop, and this is a costly loss. Speed-wise, galloping is advantageous because it compresses and stretches an animal’s trunk in a way that results in longer strides that cover more ground. According to the speed-predictive model, top human sprinters are already quite close to their maximum running speed, and only changes in human biology or technology would be expected to increase this speed threshold (University of Cologne, 2021). One such technological innovation is the Nike VaporFly 4% racing shoe, which has been found to reduce the required energetic cost/oxygen uptake of running by 4% for high-level competitors. The Nike VaporFly 4% shoe is able to accomplish this due to a combination of factors including ankle stabilization, reduction of toe flexing, and unusually high energy return in the heel. In 2019, Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge became the first person to run a sub-two-hour marathon. He accomplished this wearing the Nike AlphaFly, a post-VaporFly design (O’Grady & Gracey, 2020). Athletic advances like Kipchoge’s seem to support the idea that the world’s best runners have reached their biological limits and must rely on technology to enhance their speed further.

While Günther et al. (2021) referenced recordings of maximum animal speeds from past studies, they acknowledged that obtaining maximum effort from animal subjects in a lab is incredibly challenging, so non-naturalistic recordings could be misleading. Additionally, such studies tend to neglect external factors such as temperature, which might influence animal running performance (Günther et al., 2021). If future studies on animal speed account for such environmental factors, their results will only strengthen the accuracy of the model Günther et al. (2021) proposed. There also remains the potential to develop similar speed-predictive models for aquatic and airborne organisms. With the possibility for so many speed-predictive data available to the public for inter-species comparison, perhaps the tortoise and the hare are racing toward a world of boundless competition.

References

Günther, M., Rockenfeller, R., Weihmann, T., Haeufle, D. F. B., Götz, T., & Schmitt, S. (2021). Rules of nature’s Formula Run: Muscle mechanics during late stance is the key to explaining maximum running speed. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 523, 110714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110714

O’Grady, T. J., & Gracey, D. (2020). An evaluation of the decision by World Athletics on whether or not to ban the Nike Vapor Fly racing shoe in 2020. Entertainment and Sports Law Journal, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.16997/eslj.257

University of Cologne. (2021, July 23). Why four-legged animals are better sprinters. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/07/210723105319.htm

Related Posts

The Critical Role of Sleep in Determining Reaction to Daily Life

Source: Pixabay Sleep plays an extremely important role in physical...

Read MoreA New Method to Track Parkinson’s Disease

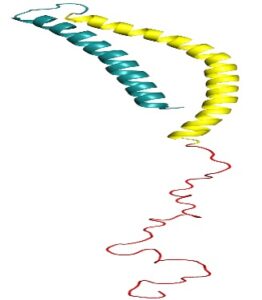

Figure 1: 3D structure of alpha-synuclein protein. Mutations in alpha-synuclein...

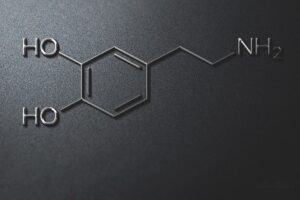

Read MoreDopamine Deficiency and Its Effects on Addiction

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst Academy 2023...

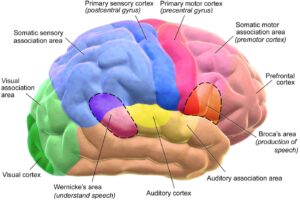

Read MoreThe Neuronal Basis for Multitasking

Figure 1: The human brain and its various functional regions. Researchers...

Read MoreUniversality of the Face: New Research Points to a Shared Human Commonality in Emotional Expression

Figure 1: Examples of emotional expressions Source: Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels Raising...

Read MoreThe Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis May Be the Missing Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Anorexia Nervosa

Figure 1: The microbiota-gut-brain axis is a bidirectional pathway of...

Read MoreCaroline Conway