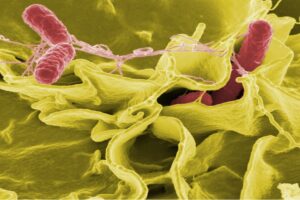

Figure: Bacteria are essential for gut health because they help break down key dietary nutrients. But when one’s diet changes– the gut microbiome can be driven out of sorts. Scientists now understand that the gut microbiome is altered by a calorie-restricted diet in such a way that it prevent dieters from keeping weight off. Future interventions might bring the gut microbiome back to a more normal state and reverse this ill effect (Source: Pixabay, WikiImages)

Background

A person trying to lose weight has three major options when it comes to cutting calories – dieting, medication, and surgery. Bariatric surgery has proven highly effective from a clinical standpoint, but bariatric surgery is expensive, and is a serious invasive procedure with potential side effects like chronic nausea, vomiting, and ulcers. Weight loss pills too can be costly and can’t be prescribed unless someone meets certain criteria (BMI > 30 or BMI > 27 with accompanying medical problems like diabetes and high blood pressure). Understandably, most people aiming to lose weight try their hand at the (relatively) less daunting prospect of dieting. But diets don’t tend to last – and failures to keep of weight can’t simply be attributed to a lack of will power to continue. Scientists now know that when people try to lose weight, the body pushes back – ratcheting up the hunger signals it sends to the brain. As soon as the diet is stopped, even for a short while, weight gain quickly starts taking off again. It is also now understood that during a diet, the microbiome changes profoundly, and that these changes may play a major role in keeping dieters from long-term weight loss success. But what if the microbiome could be treated to keep the pounds off?

Details

It seems odd that dieting would have a negative effect on the body’s microbiome – but given that the gut microbiome is responsible for processing many of the nutrients that come from our diets, it is not all that surprising that restriction of food intake would alter the balance of bacteria living in the gut. Think of the gut microbiome like a forest ecosystem – if most of the small plants were suddenly wiped off the map, this would be detrimental to the consumers (rabbits, for example) who rely on these plants for food. Then the foxes would die out because they couldn’t find any rabbits to eat, and so on. Similarly, when one changes their diet dramatically, some of the gut bacteria that relied on nutrients in the old diet die off and are superseded by others.

In the present study, researchers working together at a group of Chinese universities and medical hospitals studied the effects of a calorie restriction diet on mice. A calorie restriction diet is exactly what it sounds like: a person on the diet would identify their current level of food intake and make an effort to eat a certain percentage fewer calories. This sort of diet is commonly prescribed to diabetics (or pre-diabetics – people on the verge of developing diabetes – as a preventive measure), or for people who are overweight / obese. Generally, it is prescribed in conjunction with a regimen of physical exercise.

In their lab strain mice, the researchers found that the calorie restriction diet had a major impact on the gut microbiome – reducing the abundance of a species called Parabacteroides distasonis in the mouse gut. They further found that a specific compound, the bile acid non-12OH, was significantly depleted.

What does this all mean for weight loss? The scientists believed that the changes in the microbiome they observed might be responsible for rapid weight re-gain after the discontinuation of dieting. So, they decided to put the lost bacteria and the depleted bile acids back into the body and see if this prevented the mice from regaining weight rapidly after they stopped dieting. Remarkably, they found that for mice who had been on a calorie restriction diet, P. distasonis supplementation led to less post-diet weight gain and decreased levels of fasting blood glucose compared to mice who did not receive supplementation (high blood glucose is a hallmark of obesity and diabetes). The un-supplemented mice, by contrast, gained weight rapidly and their blood glucose was elevated – an effect often observed in humans when they go off a calorie-restricted diet. Likewise, supplementation with the depleted bile acid non-12OH had similar positive effects, preventing rapid weight regain after dieting stopped.

Takeaways

Targeting the microbiome – in conjunction with dieting – may be a good strategy for keeping weight off. A lot of further research is needed in this area. But if additional laboratory research pans out, this form of supplementation could be tested in human clinical trials. The results of this study indicate that the right kind of probiotic supplements could work wonders for people trying to lose weight, so long as scientists are able to identify exactly what microbes, and which of their molecular products, have been altered by dieting. This kind of research is time-consuming and expensive – the number of experiments performed for this study alone is staggering. Yet, the costs would undoubtedly be outweighed by the benefits of an effective weight-loss supplement. Such a drug would save countless billions of dollars in medical costs and lost productivity currently brought about by the pandemic of obesity

References

Featured Article:

Li, M., Wang, S., Li, Y., Zhao, M., Kuang, J., Liang, D., Wang, J., Wei, M., Rajani, C., Ma, X., Tang, Y., Ren, Z., Chen, T., Zhao, A., Hu, C., Shen, C., Jia, W., Liu, P., Zheng, X., & Jia, W. (2022). Gut microbiota-bile acid crosstalk contributes to the rebound weight gain after calorie restriction in mice. Nature communications, 13(1), 2060. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29589-7

Other Sources:

Bariatric surgery—Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Retrieved May 8, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/bariatric-surgery/about/pac-20394258

Benton, D., & Young, H. A. (2017). Reducing Calorie Intake May Not Help You Lose Body Weight. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617690878

Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue, & Ma 02115 +1495‑1000. (2017, August 16). The Microbiome. The Nutrition Source. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/microbiome/

How much will obesity cost the economy by 2060? (2021, November 11). https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/costs-associated-with-obesity-may-account-for-3-6-of-gdp-by-2060

Pros and cons of weight-loss drugs. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved May 8, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/weight-loss/in-depth/weight-loss-drugs/art-20044832

Taylor, R. (2019). Calorie restriction for long-term remission of type 2 diabetes. Clinical Medicine, 19(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.19-1-37

Related Posts

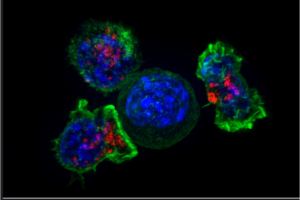

Defective Mitochondria Lead to Exhausted T Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment

Figure 1: T cells (green, blue, and red) surround and...

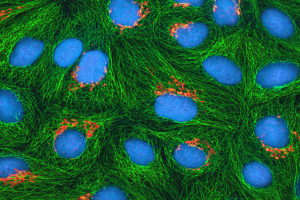

Read MoreAcoustic Reporter Genes: The Newest Breakthrough in Cell Visualization

Figure: A fluorescent protein is expressed in human epithelial cells...

Read MoreTargeting the Gut Microbiome to Keep Weight Off

Figure: Bacteria are essential for gut health because they help...

Read MoreA Spoonful of (Modified) Sugar as an Antiviral Medicine

Figure 1: A negative stain transmission electron micrograph of Influenza...

Read MoreWhy Do We Really Need Vitamins?

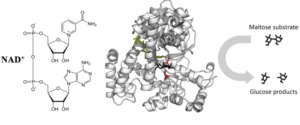

Figure 1: This figure illustrates the interaction between an enzyme,...

Read MoreInnovation Beyond All Barriers: The Arrival of a Life-Saving Treatment

Figure 1:Magnetic resonance image (MRI) – coronal slice of a...

Read MoreSam Neff