Figure: An artistic depiction of disordered eating behavior under the stress of COVID-19 (Source: The Chronicle, Shannon Fang, 2020)

Introduction

When confronted with a strong emotional situation (e.g., pain, aggression, anger, sadness, or loneliness), many people may eat pizza or chips for inner comfort. Or, hearing an exciting piece of news, some might reward themselves with ice cream or chocolate cake to keep their mood high. During these two processes, highly intense emotional arousal (either positive or negative) stimulates an individual’s impulsive drive. To an extent, these behaviors are normal responses to emotional events, but the inability to control this impulsive drive can lead to disordered eating behaviors, usually in the form of binging or purging. Importantly, it is not just binge eating that emotion-related impulsivity can trigger. Several other forms of atypical eating behavior (e.g., restriction in Anorexia nervosa, or binging and purging in Bulimia nervosa) are also possible. Nowadays, eating disorders effect upwards of 30 million people worldwide (Amanda M. Kutz et al., 2020) and are often comorbid with clinical problems including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Marcus & Marsha D., 2018; Conviser et al., 2018; Frederiksen et al, 2021; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2020).

Given that eating disorders are a fairly common phenomenon and have potentially detrimental consequences, it is imperative to investigate the underlying mechanisms and use knowledge of these mechanisms to produce more effective interventions. These underlying mechanisms are complex and require a lot of careful research to unravel – for example, disordered eating behaviors triggered by emotion-related impulsivity are not simply the same as emotional eating or binge eating, as the former involve more complex symptoms that involve sophisticated mechanisms, which will be further discussed below. These behaviors also often go undiagnosed. Many people – individuals afflicted and those around them – do not seek medical help until other serious medical side effects arise. Some may be ashamed to show vulnerability and therefore avoid asking for help. This article aims to unravel why people disrupt their regular food consumption under emotion-related impulsivity (i.e., high emotional arousal), and how researchers in the field can help individuals address this problem with smarter strategies.

Literature review of emotion-related impulsivity

Recently, the focus of impulsivity research has shifted from planning, deliberation, and attention (Barratt, 1965; Dickman, 1990) to responses to high emotional states, both negative and positive (Selby et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2019). As conceptualized in previous research, emotion-related impulsivity (or impulsivity to emotion; ERI) refers to the tendency to react impulsively when experiencing high emotional states, usually in the form of reflexive and automatic thinking, speech, and behaviors like eating (Whiteside & Lynam, 200; Carver & Johnson, 2018).

The notion of emotion-related impulsivity stems from the influential UPPS model of impulsivity, which distinguishes Negative Urgency (the tendency to act impulsively in negative mood states) from other forms of impulsivity (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Whiteside et al., 2005). Later, researchers extended this model by including Positive Urgency (i.e., the tendency to act impulsively in positive mood states) (Cyders et al., 2007). Fischer et al. (2007) found that Negative Urgency differentiated eating disordered and substance abusers from controls, whereas Cyders et al. (2007a) found that Positive Urgency differentiated substance abusers from both eating disordered and control individuals. More recently, regardless of the emotional valence, Positive and Negative Urgency have been grouped into a higher-order factor called emotion-related impulsivity which includes impulsivity in both positive and negative contexts (Carver et al., 2011; Cyders & Smith, 2008; Carver et al., 2008; Zorrilla & Koob, 2019).

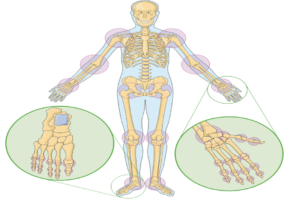

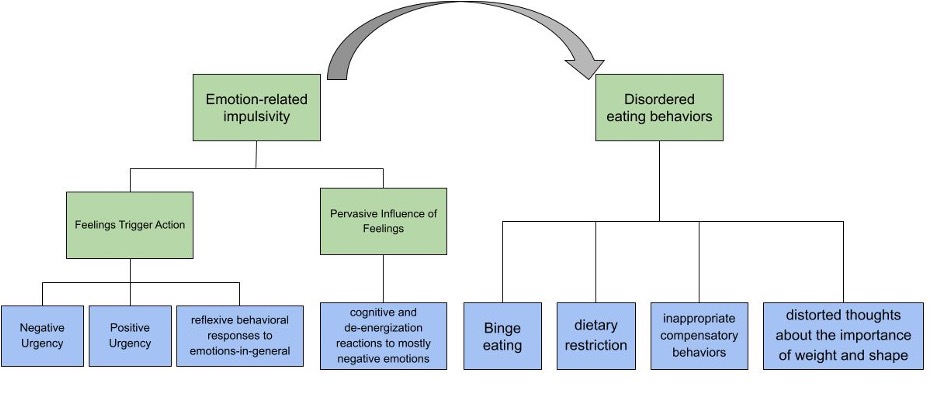

Moreover, in revising the scope of emotion-related impulsivity, Carver and colleagues collected a broad set of items assessing emotion-related impulsivity, conducted exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, and generated a three-factor impulsivity index: “Feelings Trigger Action,” “Pervasive Influence of Feelings,” and “Lack of Follow Through” (2011). Specifically, “Feelings Trigger Action” refers to the rash and often regrettable response to positive or negative emotions, and “Pervasive Influence of Feelings” reflects the tendency of a person’s emotions to influence motivation, self-view, and perception of the world in an unconstrained and often irrational manner (Cyders & Smith, 2008). These two components are concerned with the reflexive responses to emotions. This paper uses the broad definition of emotion-related impulsivity, consisting of Feelings Trigger Action (i.e., Negative Urgency, Positive Urgency, and reflexive behavioral responses to emotions in general) and Pervasive Influence of Feelings (i.e., unconstrained effects of mostly negative emotion on cognition and motivation).

Important to note is the fact that measures of emotion-relevant impulsivity are separable from other forms of impulsivity, such as lack of premeditation, sensation seeking, and lack of perseverance, and have differential validity (Whiteside & Lynam 2001; Sharma et al., 2014; Berg et al., 2015; Whiteside et al., 2005). In previous studies, emotion-related impulsivity has been studied from the perspective of (a) personality traits, (b) effective science, (c) cognitive abilities, and (d) pathological symptoms. For example, (a) some studies suggest that emotion-related impulsivity results from a trait-like predisposition to exhibit impulsiveness in response to emotional stimuli (Sharma, L. et al., 2014). (b) Emotionality (i.e., the degree to which an individual experiences and expresses emotions, irrespective of the quality of the emotional experience) is one core feature that separates emotion-related impulsivity from other forms of impulsivity. Researchers have recently been focusing on the heightened responses to a broad range of motivational and emotional states, especially negative mood states (Carver et al., 2018). (c) Emotion-related impulsivity is closely related to response inhibition (or cognitive control), the paramount of preferential responses (Pearlstein et al., 2019). In addition, (d) impulsive responses to strong emotions are increasingly recognized as a common feature of many different forms of psychopathology, such as borderline personality disorders and eating disorders (Johnson et al., 2013).

Notably, emotion-related impulsivity has been more robustly related to psychopathology than other forms of impulsivity (e.g., lack of premeditation, sensation seeking, and lack of perseverance) (Berg et al., 2015). Indeed, compared with other forms of impulsivity, emotion-related impulsivity was found to be the most robust predictor of every psychopathology or symptom group, including anxiety, depression, and eating disorders (Berg et al., 2015). Several studies have investigated the association between eating disorder symptoms and the UPPS(-P) dimensions in community and clinical samples (Racine et al., 2017). Negative Urgency was positively associated with bulimia nervosa symptoms with moderate to high effect sizes, while the relationship between the other impulsivity dimensions and bulimia nervosa showed small effect sizes (Johnson et al., 2013). Particularly, in clinical samples, emotion-related impulsivity could predict lower life quality, higher rates of comorbidity, self-injury, suicidal action, aggression, and poor social well-being (Auerbach et al., 2017; Muhtadie et al., 2014; Victor et al., 2011). A growing body of longitudinal research supports the predictive power of emotion-related impulsivity in the onset and course of psychopathological problems such as eating disorders (Riley et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013; Pearson et al., 2012).

Empirical Evidence in emotion-related impulsivity and disordered-eating behaviors

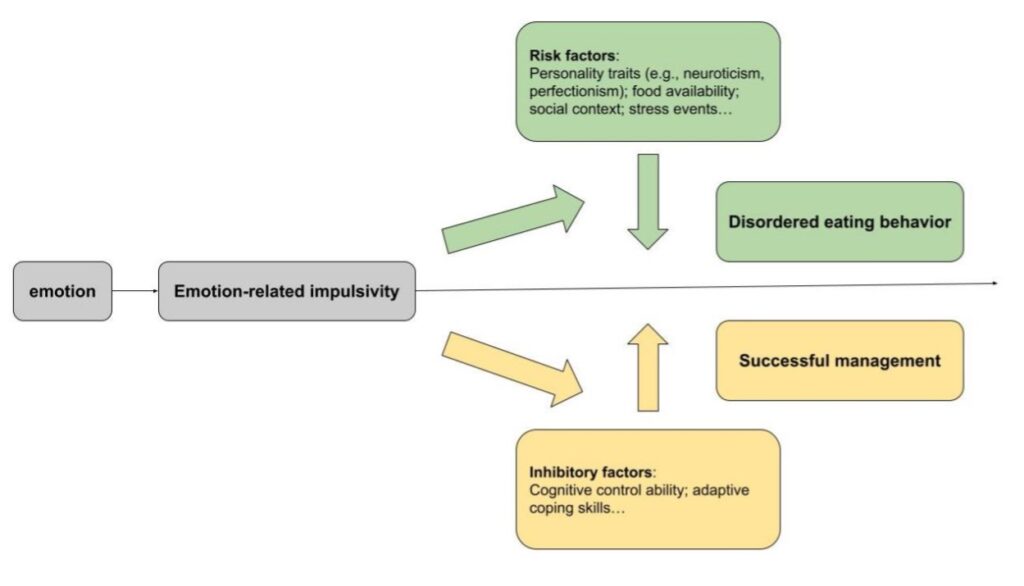

Figure 1: Illustration of the relationship between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating behavior. (Source: Image Created by Author)

Disordered eating behavior (not a diagnosis) normally consists of signs or symptom-like patterns in dietary restriction, binge eating, inappropriate compensatory behaviors, and/or distorted thoughts about the importance of weight and shape (Fergus et al., 2019; Masuda. A et al., 2012; Moore, M et al., 2014; Petrie et al., 2008). The precise relationship between impulsivity and disordered eating has been difficult to determine because many studies employ conflicting definitions of impulsivity (Fischer et al., 2008). Because previous studies have suggested a link between emotion-related impulsivity, this article specifically focuses on the emotion-related form of impulsivity (Riley et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013; Pearson et al., 2012). In other words, disordered eating would be considered an impulsive response to emotional stimuli.

Much attention has been previously deployed to the personality and psychopathology view. For example, one study sampled a group of adults with or without binge eating disorder (BED) and recorded their scores on impulsivity, eating disorder psychopathology, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Results indicate that those with BED exhibit greater Negative Urgency than those without BED (Therese E Kenny et al., 2018). Similarly, women with a lifetime history of binge eating, uncontrolled eating, or overeating reported greater Negative Urgency than women with no reported history of these episodes (Racine et al., 2015). Additionally, females appear to be especially vulnerable to this relationship. One recent meta-analysis found that Negative Urgency is related to bulimia nervosa symptoms in women (r=.40, p < .001) (Fischer et al., 2008). Another study in elementary school-age girls found that Negative Urgency concurrently predicts both binge eating and purging behavior (Pearson et al., 2010). Moreover, individual differences in expectations that eating helps manage negative emotional states have been found to predict the occurrence of binge eating in adolescent girls (Smith et al., 2007). In this research, self-reported emotion-related impulsivity is considered an inherent risk factor that makes individuals vulnerable to disordered eating.

In addition to general self-report measures, researchers also examined emotion-related impulsivity as a state-dependent variable in laboratory settings with artificial manipulation. Typically, in these laboratory studies, following positive or negative emotion induction, participants completed a series of behavioral tasks testing working memory and response inhibition (Dekker, M. R., & Johnson, S. L., 2018; Pearlstein et al., 2019). Participants with high emotion-related impulsivity often showed greater deficits in inhibitory control. However, studies examining inhibition response in disordered eating under emotion-related impulsivity remain insufficient. It is noteworthy that although classical paradigms like stop-signal tasks and go/no-go tasks have been validated in testing inhibitory control, there is still a difference between reacting to the food in the picture and eating it. For example, participants in these studies typically need to inhibit their response when viewing food pictures and press the “Go” button when viewing non-food pictures. The food and non-food picture stimuli would display in random order. Those whose impulse control was poor tended to have a quicker reaction in response to food stimuli, and have a greater probability of making mistakes and reacting when they shouldn’t (Stice et al., 2017) .

Why is it that individuals high in emotional impulsivity may be prone to disordered eating behaviors? One possible explanation is that many urgent behaviors, such as overeating, tend to relieve distress through the reinforcement they provide and by distraction from the initial distress (Agras & Telch, 1998; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). For example, males often report feeling happy after overeating (Leon et al., 1985). Thus, binge eating is reinforced, and over time, high-urgency boys develop expectations that binge eating provides pain-relieving rewards. This expectation, in turn, increases the likelihood of overeating in the future. However, studies on females found different results. Several ecological momentary assessments (EMA) studies -a research methodology that involves repeated assessment of participants over time in their naturalistic environments- found that female participants report high levels of negative affect on days that include a binge and/or a compensatory behavior and report increasing levels of negative affect before a bulimia nervosa event (Smyth et al., 2007, Wegner et al., 2002). A comparison study between males and females is needed.

Correlation studies like the ones discussed so far are not adequate to explain why emotion-related impulsivity might lead to disordered eating. Turning to five main mechanisms (i.e., physiology, cognitive control, emotion mechanisms, neural correlates, and social risk factors) may help further explain this relationship.

Physiological impairments

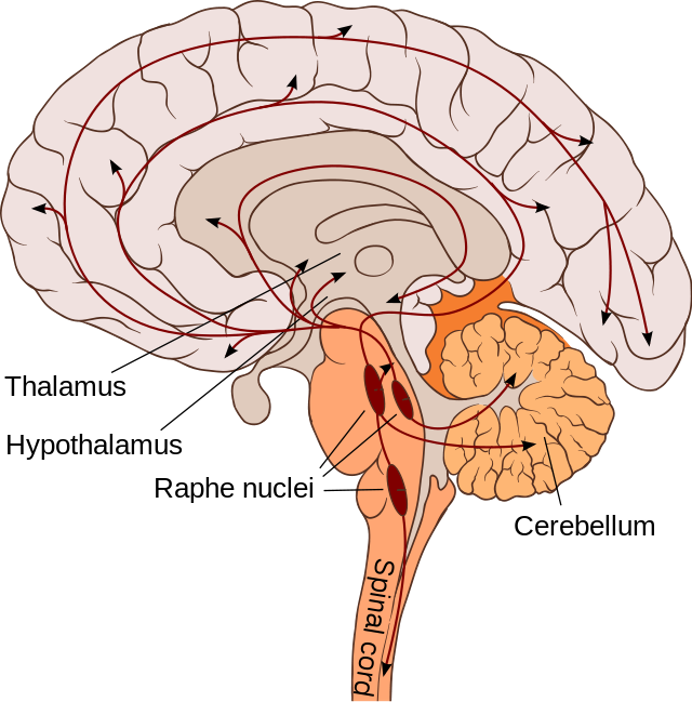

Central serotonergic pathways

Known as a neurotransmitter that modulates a wide range of neural and neuropsychological processes, serotonin plays a central role in constraint over impulses, particularly, emotion-related impulses (Depue, 1995; Spoont, 1992). Emotion-related impulsivity was found to be tied to an impaired function of the serotonergic system (Carver et al., 2018). Researchers studying reflexive (i.e., automatic) and reflective (i.e., deliberative) response systems have suggested that lower serotonergic function engenders a relatively weaker function of the deliberative system, and thus promotes impulsive reactivity to emotion (Carver, Charles S; Johnson, Sheri L. 2018).

Figure 2: Illustration of central serotonergic pathway. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Paradiso et al., 2007)

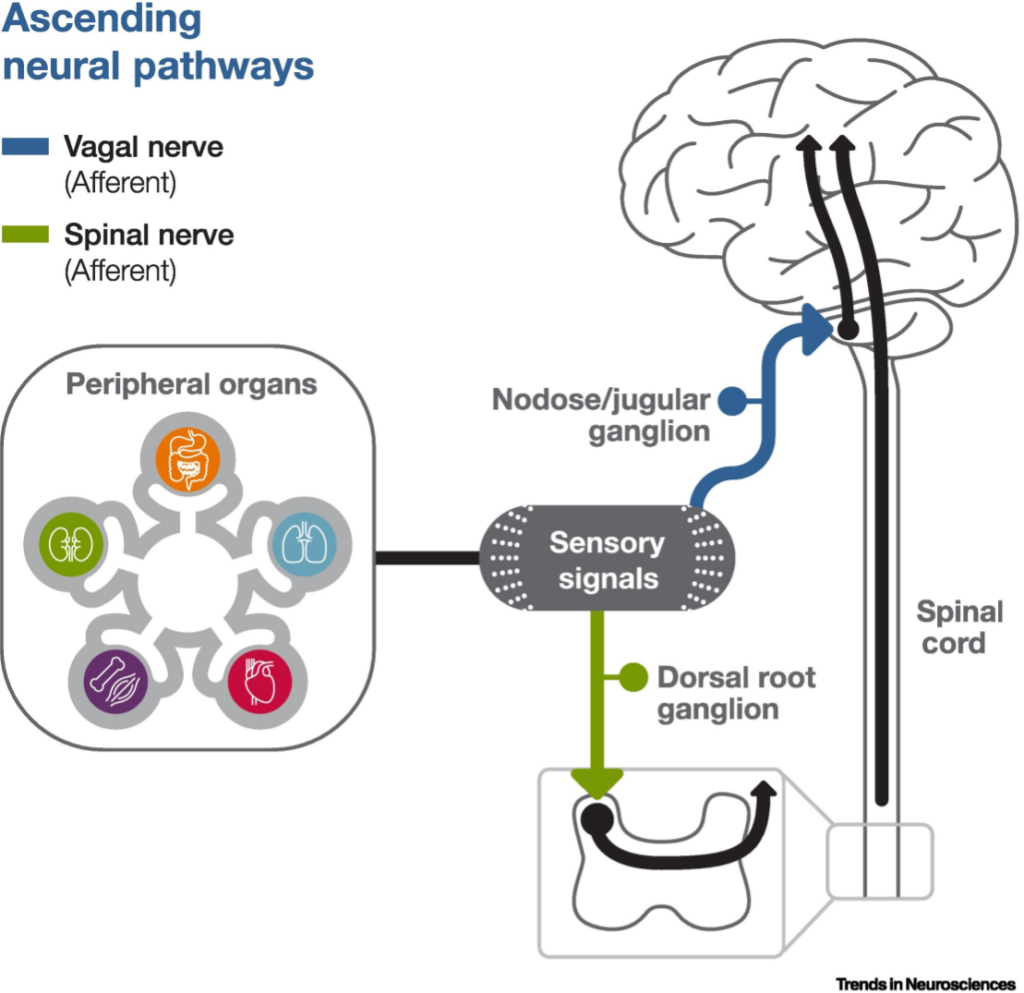

Interoceptive ability

In addition to focusing on the external reaction to emotional stimuli, one might further consider the internal reaction. One might assume that people who are vulnerable to disordered eating under emotion-related impulsivity may have impairments in emotion recognition. That is, problems arise in recognizing emotions in the first place before individuals process and react to emotional responses later. In this case, individuals impulsively engage in disordered eating not because of weak deliberative control but because of the initial misinterpretation of emotional stimuli.

For instance, take interoception, the foundation of the embodied self which is deeply grounded in the body and the body’s interaction with the environment (Apps & Tsakiris, 2014; Herbert & Pollatos, 2012). Dysfunctional interoception is at the core of many psychosomatic disorders (Todd, et al., 2022). As a homoeostatic (i.e., working to maintain a balanced energy intake) and allostatic (i.e., responsive to stressors that disrupt the body’s state of balance) psychophysiological need, eating is intrinsically guided by interoceptive signals (Vitale et al., 2022) .

In the dimensions of interoception, the fourth dimension “Interoceptive Emotional Evaluation” reflects individual subjective appraisal related to perceptions of interoceptive signals and refers to the effective evaluation of one’s internal signals along specific emotional dimensions (Herbert, et al., 2012). Specifically, negative evaluation of interoceptive signals such as negative or ambivalent reaction to food and hunger and fullness as well as negative body image is part of the clinical core symptoms in disordered eating behaviors (Young et al., 2017).

Therefore, deficits in interoception may promote misinterpretation of emotional stimuli that leads to emotion-related impulsivity. However, this is just a hypothesis and more qualitative evidence is still needed in this regard.

Figure 3: Illustration of interoceptive system. (Source: Google Photos, Wen G. Chen et al., 2021)

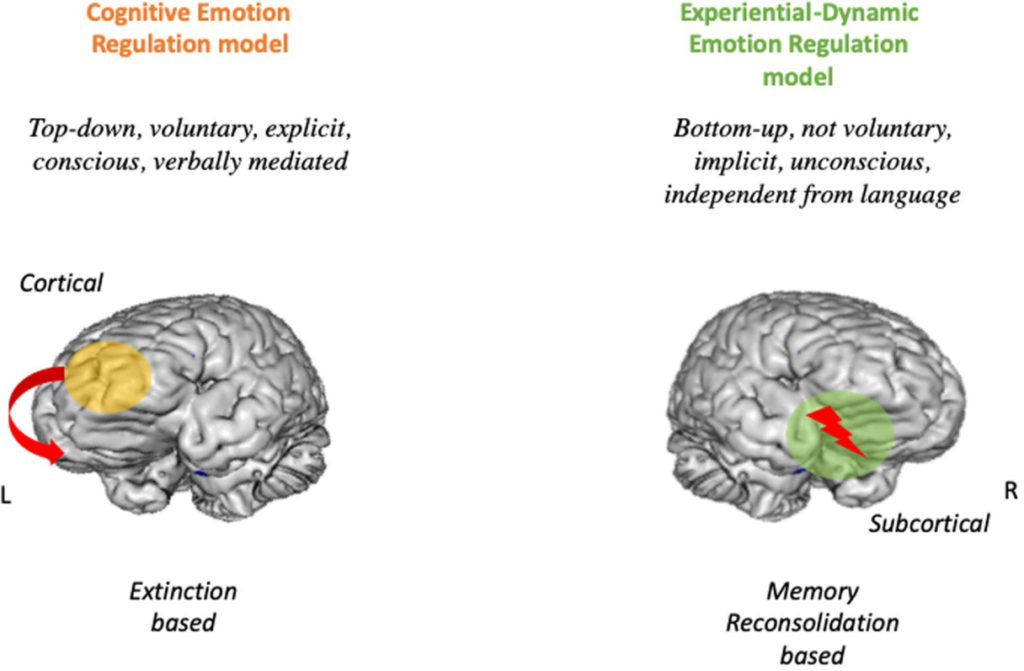

Cognitive control

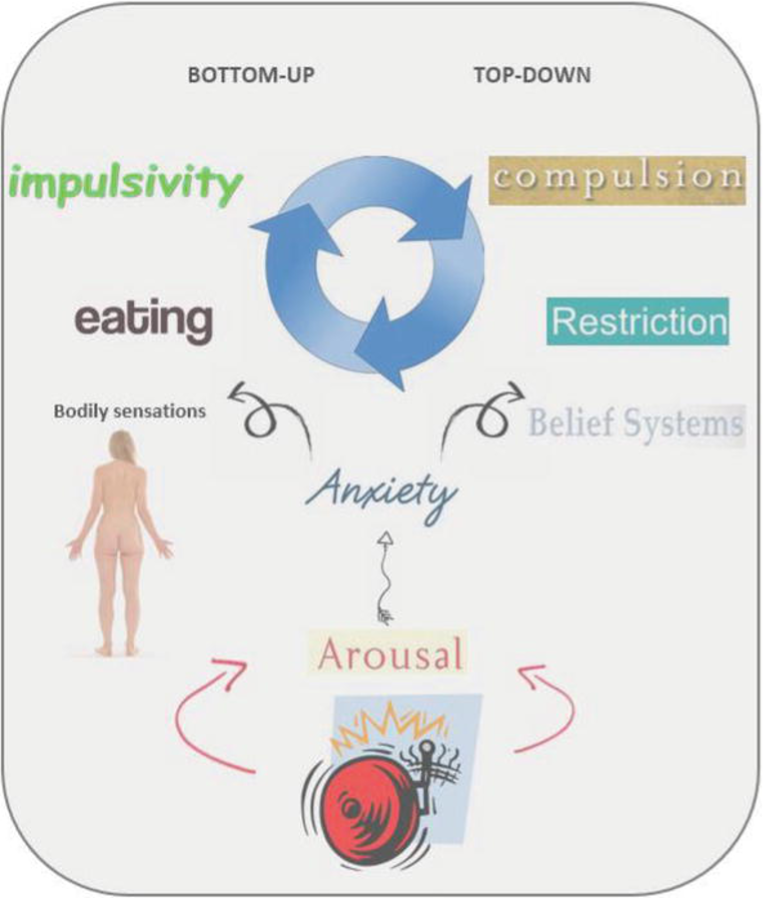

At a conceptual level, multiple theories state that impulsivity, including emotion-related impulsivity, might be best understood within the two-mode models (Carver et al., 2008). These models describe how the tendency to react impulsively when experiencing strong emotion is shaped by the relationship between a bottom-up, reflexive system (automatically initiating responses without deliberation) and a top-down, reflective system (cognitively controlled) (Carver et al., 2018). Consistent with two-mode models, empirical evidence indicates that deficits in top-down cognitive control overlap substantially with many behavioral conceptualizations of impulsivity (Sharma et, al., 2014).

Figure 4: Illustration of dual process of cognitive control. (Source: Google Photos, A. Grecucci, 2020)

Response Inhibition

A growing body of empirical research suggests that difficulty in controlling impulses in high emotional states represents a deficit in response inhibition (Bechara & Van der Linden, 2005; Carver et al., 2008; Bari & Robbins, 2013). In addition to impulsivity, deficient or impaired response inhibition has been found in many forms of psychopathology, such as eating disorders (Snyder et al., 2015). Thus, cognitive control deficits in response inhibition might be the common factor linking disordered eating and emotion-related impulsivity. Response inhibition is a specific aspect of cognitive control that corresponds with the ability to go beyond planned or initiated actions or to inhibit the tendency to respond automatically or effectively (Aichert et al., 2012).

One study enrolled undergraduates who completed a self-report on Positive Urgency, underwent several positive mood inductions, and submitted to behavioral measures of impulsivity and cognitive control. Positive Urgency scores were significantly correlated with poor task performance. Specifically, those with Positive Urgency scores exhibited poor prepotent response inhibition but were not deficient in other performance measures. Findings thus implicate deficits in response inhibition as one mechanism involved in emotion-related impulsivity (Johnson, S. L. et al., 2016).

Cognitive resource depletion

Turning to the point of cognitive resource depletion, it seems that people put more cognitive resources into mediating the conflict between emotional expression and suppression that there is little left to maintain cognitive control over emotional responses. Cyders and Smith argue that among persons with high levels of Urgency, greater presence of emotion diminishes the cognitive resources available to constrain emotional responses (2008).

Despite these findings, caution is warranted in that effect sizes of outcome in past studies have been fairly small (r<0.3) and have emerged only among sample populations with higher impulsivity levels (Carver et al., 2018). Nonetheless, recent findings agree with the aforementioned observed behavioral effects in identifying a differential profile of activation of the frontoparietal network (a control network serving to rapidly and instantiate new task states by flexibly interacting with other control and processing networks) during a response inhibition task for those with high emotion-related impulsivity (Chester et al., 2016; Wilbertz et al., 2014).

Taken together, both deteriorations in response inhibition and deficiency in the cognitive resource can account for the failure to manage disordered eating under emotion-related impulsivity.

Emotional Mechanisms

Three features of emotion would impact the association between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating: the forms of emotion, emotional valence (i.e., positive versus negative), and arousal level.

Present form of emotion

The present form of emotion refers to the level of emotion-related impulsivity one experiences depending on whether the emotion is proactive or reactive (Martins-Klein et al., 2020). For instance, a study found that emotion-related impulsivity modestly correlates with proactive aggression (enacted in service of the desired outcome), but more robustly related to reactive aggression (which occurs in response to negative emotions, typically anger) (Lynam & Miller, 2004). In this sense, the emotion-related impulsivity encountered is more of a reactive response to external stimuli than a tool used to actively achieve a certain result.

Emotional valence

In terms of emotional valence, studies suggest that people tend to soothe themselves with comfort food when dealing with negative emotions and maintain their happiness with rewarding food under a positive emotional state (Selby et al., 2020). For example, relationships between binge eating and Negative Urgency reflect impairments in behavioral control over eating when upset. One study concludes that Positive Urgency is significantly associated with binge eating (Cyders et al., 2007; Cyders & Smith, 2008). Within the model, focusing on failures of top-down control over emotion as a possible mechanism driving emotion-related impulsivity, researchers suggest that regrettable behavior may reflect a reflexive response to strong emotions (Carver et al., 2008). These reflexive responses are thought to differ by type of emotion. For instance, reflexive responses to anger may encompass impulsive aggression, and reflexive, unconstrained responses to sadness may involve passivity and loss of motivation (Carver et al., 2008).

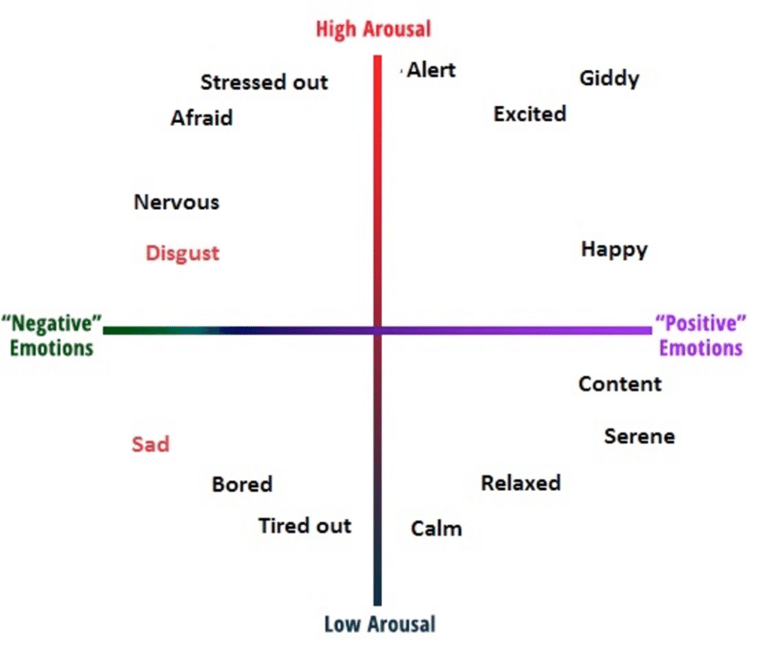

Emotional arousal

One study suggests that, rather than valence, the most important feature of emotion leading to impulsive behaviors is arousal (Pearlstein et al., 2019). Because tendencies to respond impulsively to heightened emotion occur across both positive and negative emotions, heightened arousal, rather than valence, may be the more important trigger (Cyders et al., 2007). Therefore, it seems reasonable that higher emotion arousal implies more food intake (in the case of binge eating).

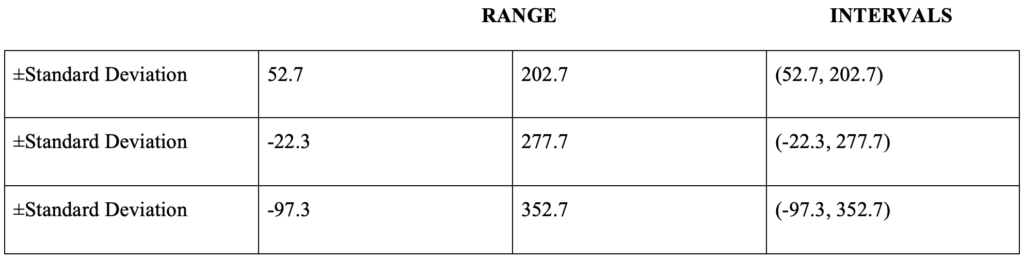

Table 4

D.1.RESULTS:

Figure 5: Illustration of two dimensions of emotion. (Source: Google Photos, Enrique Munoz-De-Escalona & José J. Cañas, 2017)

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that individuals with high levels of emotion-related impulsivity are not simply more emotionally reactive; in fact, most studies suggest that comparable emotional arousal levels differentially trigger impulsive responses among persons with high emotion-related impulsivity (Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2010; Johnson et al., 2016). It thus appears that this form of impulsivity is not explained by emotional arousal alone. To provide a plausible explanation for these findings, researchers in the field have introduced concepts such as neural correlates and social risk factors.

Neural correlates

Many of the neural regions identified as being associated with emotion-related impulsivity (especially Negative Urgency), appear to overlap with neural circuits found to be associated with disordered eating (Um et al., 2019). Structurally, differences in gray matter volume were found in the caudate nucleus, dorsal striatum, medial orbitofrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and right lenticular nucleus in individuals with disordered eating (Amianto et al, 2013; Brooks et al, 2011; Frank et al., 2013). Functionally, studies have found altered neural activation in the ventral striatum, insula, medial frontal gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, amygdala, and ventral putamen in individuals with disordered eating patterns compared to healthy controls (Bohon et al., 2011; Brooks et al., 2011; Frank et al., 2011). Correspondingly, disordered eating and Negative Urgency show similar disruptions in several brain regions associated with reward and decision-making processes; including the ventral and dorsal striatum, insula, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, and amygdala. Similarities between these brain regions support previous research that found significant associations between eating disorders and measures of Negative Urgency (Harrison et al., 2019).

Social risk factors

One prominent feature of disordered eating behaviors under emotion-related impulsivity is purging, especially after binge eating. One study has found that appearance pressures, thin-ideal internalization, and body dissatisfaction significantly moderated the association between Negative Urgency and binge eating. High levels of these risk factors and Negative Urgency are associated with the greatest binge eating (Racine et al., 2017).

Furthermore, in a review article, Erik Hemmingsson suggests that socioeconomic adversity, family stress and dysfunction, offspring insecurity, and stress can cause emotional turmoil, low self-esteem, and poor mental health in individuals (2018). Excessive consumption of high-calorie or high-fat foods can act as self-medication to alleviate psychological distress and emotional distress (Erik Hemmingsson, 2018).

Additional Thoughts

The origin of emotional impulsivity

One primary objective of previous research has been to reveal how emotion-related impulsivity arises. That is, what creates Negative Urgency, Positive Urgency, and reflexive response in general?

Take Negative Urgency, for example. Sharma and colleagues suggest that Negative Urgency creates negative affect and mood states (2014). Meanwhile, other researchers claim that Negative Urgency is a tendency towards impulsive reactivity to the emotions created by the underlying personality trait of neuroticism (a broad personality trait dimension representing the degree to which a person experiences the world as distressing, threatening, and unsafe) (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Carver & Sheri L. Johnson, 2018). Additionally, given the fact that disordered eating is characterized by critical distortion of body perception from the inside (interoception) and the outside (exteroception), factors such as cognitive distortion and perfectionism may also account for the emergence of food-related emotional impulsivity.

Comorbid disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia may exacerbate emotion-related impulsivity propensity. More specifically, emotion-related impulsivity may be a secondary symptom of these psychiatric disorders. For example, one study found that individuals with bipolar disorder have an increased risk of developing eating disorders or disordered eating symptoms compared to the general population (McDonald et al., 2019). Further, there may be a dose-response relationship between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating. This is especially the case for binge eating. For those who are highly concerned about body image, the intensive remorse they experience following over-eating (triggered by emotional stimuli) may lead to further impulsive behavior such as compulsive purging, forming a self-reinforced vicious circle.

Non-planning vs. pre-planned impulsivity

Consider to the widely used Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS), which measures emotion-related impulsivity from (1) attentional impulsivity to (2) motor impulsivity to (3) unplanned impulsivity (Ireland et al., 2008). Recent research shows that emotion-related impulsivity is more than just “non-planning.” It also occurs in pre-planned situations where individuals weigh the rewards from emotion-related impulsivity against the rewards of response suppression (Terres-Barcala et al., 2022). Another possible explanation is that individuals may lack sufficient cognitive resources or have an impaired deliberative system (Carver, Charles S; Johnson, Sheri L et al., 2018). This is also related to an individual’s reward sensitivity and ability to delay discounting (Robinson et al., 2021). Given that people who engage in emotion-related impulsivity often experience regret and self-blame, further research is wanted on why some people still choose emotion-related impulsivity, even though they may have anticipated potentially negative outcomes (Sokić et al., 2020).

Unstoppable compulsion vs. one-time impulsivity

Emotion-related impulsivity is not a one-time event in an individual’s life, but in fact, someone who is high in emotion-related impulsivity will likely fall into the same or similar traps repeatedly Everyone can fall into impulsiveness for some reason, and people who are more sensitive to emotional cues are more likely to behave impulsively, have difficulty stopping once they start crying, or lose their temper and become aggressive (Johnson et al., 2020). The biggest difference with emotion-related impulsivity, however, is that once an individual experiences an impulsive drive, it cannot be suppressed or stopped (Carver et al., 2018). This involves the relationship between impulsivity and compulsion. Previous research has shown that some people make impulsive decisions compulsively (Deserno et al., 2020). Since obsessive-compulsive disorder has been found to play a role in the development, maintenance, and relapse of eating disorders, it is critical to identify the mechanisms of compulsive urges in this condition (Deserno et al., 2020). For example, body checking (i.e., seeking information about body’s size, shape, appearance, or weight by picking at one’s abdomen, trying to feel bones, weighing oneself frequently, zeroing in on specific body parts in the mirror, etc.) is a compulsive behavior before and following negative affect, which may maintain the cycle of disordered eating behavior through negative reinforcement (Pak, K. N. et al., 2018). Some have suggested that repetitive thinking (such as rumination) may be a key factor, but further validation is needed (Dawson et al., 2018).

Figure 6: Illustration of how impulsivity and compulsivity may interact with bodily sensations (bottom-up) and belief systems (top-down) in binge-eating and restricting anorexia nervosa (AN). (Source: Google Photo, Samantha Jane Brooks & Helgi Schiöth, 2019)

Measurement of emotion-related impulsivity

One obstacle to the research discussed above is that impulsiveness in emotion-stimulating situations is difficult to measure. This is mainly because the emotions people experience are highly subjective, and individuals vary in their emotional expression. Although different perspectives have been adopted on the matter, emotion-related impulsivity has been widely measured as a self-reported variable. The most common measure of emotion-related impulsivity is the Negative Urgency Scale derived from factor analysis, which measures a lack of control over responses to most negative affective states (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). A parallel Positive Urgency Scale reflects a lack of control over responses to positive affective states (Cyders et al., 2007). To provide a more reliable test, researchers have recently created a new tool named the “emotional stop-signal task” to check for Negative Urgency (Kenneth J. D. Allen et al., 2021). The results suggest that recklessness in high emotional states may be related to quicker and more accurate experiment performance. Given that such an experiment task can trigger participants’ real-time emotional reactions, it may reveal more accurate emotion-related impulsivity characteristics than self-reported surveys that may be flawed by social desirability.

Other disordered eating behaviors

The amount of research on emotion-related impulsivity and specific eating disorders is notably unbalanced. Most of the existing research is on emotion-related impulsivity and binge eating disorders. In such cases, more severe symptoms occur in the presence of emotion-related impulsivity. Other symptoms, such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa, can also cause the afflicted individual to suffer. For example, aggression and emotion-related impulsivity have been found in laxative anorexia and bulimia nervosa (Zalar et al, 2011; Izydorczyk & Bernadetta, 2013). Dysphoria is another emotional state that may increase the risk of emotion-related impulsivity. For example, in the case of bulimia nervosa, restrained eaters with distorted notions of thinness may feel frustrated with their bodies, and this immediate frustration may prompt them to overeat and then report purging. However, research on these disordered eating behaviors under emotion-related impulsivity remains sparse, and the types of emotions that have been studied are limited.

The emotion processing framework

Research thus far has extensively focused on impulsivity, eating disorders, and emotion dysregulation, which is the third phase of the emotion processing framework (Williams et al., 2008). The emotion processing framework includes emotions, thinking and feelings (such as implicated in alexithymia, which is an individual’s inability to identify emotions experiences and is highly reported in individuals presenting with eating disorders), and self-regulation (emotion regulation) (Johnson et al., 2020). The first two stages need further research as well. Given that emotion-related impulsivity is characterized by transient arousal and inhibition deficits, a comprehensive study of the first two stages of the relationship between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating would be helpful.

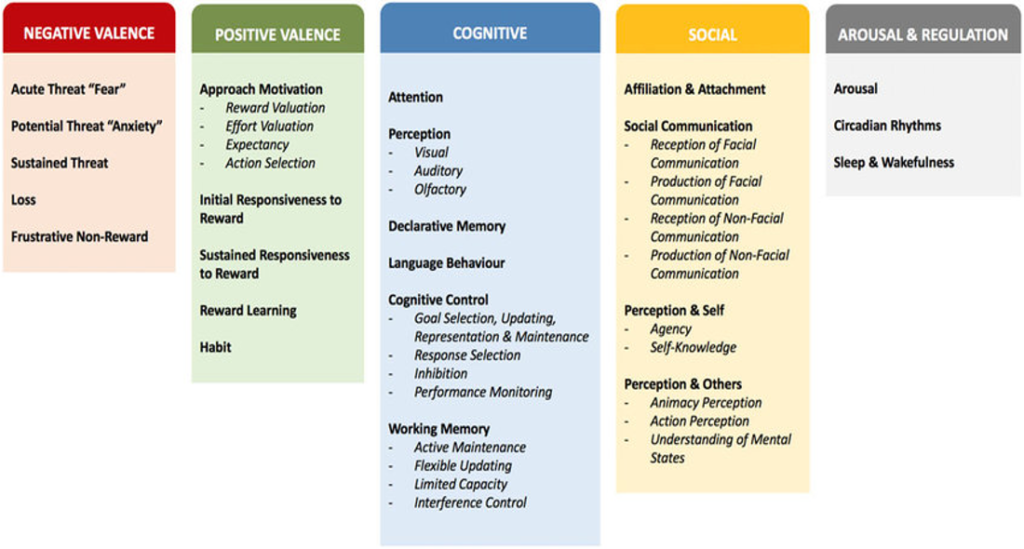

The RDoC framework

Despite the potentially detrimental effects it may generate, emotion-related impulsivity has not been categorized as a diagnosable disorder. In psychopathology, researchers have discussed the role emotion-related impulsivity plays in the p factor, a higher-order entity that encompasses and adds to the information provided by general psychopathology, embodied in the research domain operating criteria (RDoC) (Caspi et al., 2014; Carver et al., 2017; Cuthbert, 2015; Cuthbert & Insel, 2013).

Figure 7: Description of the RDoC framework. (Source: Google Photo, Murat Yucel et al., 2019)

The RDoC framework is a research strategy that is implemented as a matrix of elements (Mittal et al., 2017). The matrix is a dynamic structure that currently focuses on six major domains of human functioning (e.g., Negative Valence Systems, Cognitive Systems). Contained within each domain are several behavioral elements, or constructs, that comprise different aspects of its overall range of functions. Constructs are studied along a span of functioning from normal to abnormal with the understanding that each is situated in and affected by environmental and neurodevelopmental contexts (Mittal et al., 2017).

Under the RDoC framework, emotion-related impulsivity is called the trans-diagnostic factor (Carver et al., 2018). A “transdiagnostic process” is the label given to a mechanism that is present across disorders, and which is either a risk or maintaining factor (a factor which helps perpetuate symptoms) for the disorder (Michael Amlung et al., 2019). In this sense, further study on the relation between emotion-related impulsivity and factors in the RDoC framework is important.

Potential prevention or intervention

Taken together, emotion-related impulsivity has been considered as a risk factor for a range of psychopathologies, including disordered eating (Amlung M et al., 2019). Studies have shown that maladaptive eating behaviors can alleviate extremely negative emotional states in the short term (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). Thus, short-term relief from negative emotions increases the likelihood that these behaviors will be used again and reduces the likelihood of more adaptive responses (Hawkins & Clement, 1984). These studies suggest that disordered eating behaviors manifest as avoidant coping approaches or self-defense patterns as individuals attempt to protect themselves from emotional distress through impulsive behaviors (Ferriter & Ray, 2011).

Shifting research perspectives would not change the potentially negative outcomes and risky nature of emotion-related impulsivity, but it might provide new directions for preventive intervention. More specifically, seeing emotion-related impulsivity as a form of self-defense or self-protection reframes it as a natural human function which is malleable for change.

In some studies, emotion-related impulsivity has been found to predict treatment response and outcome. For example, a decrease in Negative Urgency levels is associated with a decrease in bulimia nervosa symptoms (Anestis et al., 2007). In a study of patients with binge eating disorder, higher levels of Negative Urgency at the start of treatment were associated with poorer clinical outcomes and slower response to treatment during an acceptance-based group psychotherapy process (Manasse et al, 2016).

Recognizing this relationship between Negative Urgency and treatment outcome, scientists have proposed a wide range of methods to target emotion-related impulsivity, and hopefully treat the disorder at the source.

Emotion regulation skills

The implementation of treatment interventions that address emotional regulation with strategies to cope with impulsivity and reinforcement sensitivities (one of the major biological models of individual differences in emotion, motivation, and learning) have been found effective in improving disordered eating behavior (Pisetsky et al., 2017). For example, emotion-related impulsivity is reduced through brief, readily available interventions that include teaching individuals to recognize emotions, employ self-calming techniques to cope with emotional states, and pre-plan coping strategies for high emotional states (Johnson et al., 2020).

Cognitive vs. less cognitive demand

Cognitive training, which aims to improve individual emotion regulation, clinical symptoms, and adaptive community function by enhancing the recipient’s cognitive process, has been found to reduce emotion-related impulsivity (Peckham et al., 2018). For example, researchers have previously conducted a two-week and six-session cognitive training for participants with elevated emotion-related impulsivity scores, and they showed a significant decline in emotion-related impulsivity from pre-training to post-training and at two-week follow-up (Peckham et al., 2018). However, another study also suggests that interventions that require less cognitive effort may generate greater benefits (Carver et al., 2018). This is because emotion-related impulsivity is characterized by momentary deficits in cognitive control, indicating that intervention or treatment involving less cognitive demand may be more effective (Carver et al., 2018). Therefore, further attempts in designing potent cognitive training interventions are needed. For example, future research can compare high and less cognitive-demand intervention programs in Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials (RCTs; the gold standard for ascertaining the efficacy and safety of a treatment).

Application of neuroscience findings

The RDoC framework endorses a transdiagnostic view of mental disorders and provides progressive guidelines for neuroscience research. Future work should utilize these convergent patterns in the development of animal models of emotion-related impulsivity, in the identification and testing of prime pharmacological and physiological interventions, and as objective biomarkers to be used when testing behavioral, pharmacological, and physiological intervention effectiveness. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to consider functional connections or interactions between different brain regions or large-scale brain networks which is necessary for more effective pharmacological or physiological treatment design (Muhlert, N., & Lawrence, AD, 2015).

Conclusions

This article reviews the association between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating behaviors, paying large attention to why individuals fail to control emotion-related impulsivity. Physiological, cognitive, emotional, neural, and social mechanisms were discussed, and potential interventions were considered. In an attempt to gain a deeper comprehension of emotion-related impulsivity and its relation to disordered eating behavior, several extra thoughts were also put forward, including the triggering role of emotions, non-planning and pre-planned impulsivity, compulsivity and impulsivity, the evolving measurement of emotion-related impulsivity, and the RDoC framework.

The present article is a call to learn more about emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating. Research in this area needs constant updating and validation, as well as consideration of new studies that will drive the field of research forward.

Several future directions can be considered as a start. For one, in addition to the current theoretical components of emotion-related impulsivity, additional aspects such as initial emotion or sensory input recognition (interoceptive awareness) may provide further explanation for emotion-related impulsivity-disordered eating association, but need further empirical validation. It will also be important to develop well-validated assessment tools to measure mixed-mood emotion-related impulsivity across self-reported and clinician-rated instrument domains (Jaggers, J. A., & Gruber, J., 2020). Finally, future research should carefully consider lifespan approaches that consider emotion-related impulsivity in the context of disordered behavior onset, risk, and recurrence at critical developmental junctures throughout the lifetimes of effected individuals.

Figure 8: Hypothesis model of the relationship between emotion-related impulsivity and disordered eating behavior. (Source: Image drawn by author)

References

Agras, W. S., & Telch, C. F. (1998). The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating disordered women. Behavior Therapy, 29(3), 491-503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(98)80045-2

Aichert, D., Wöstmann, N. M., Costa, A., Macare, C., Wenig, J. R., Möller, H., Rubia, K., & Ettinger, U. (2012). Associations between trait impulsivity and prepotent response inhibition. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 34(10), 1016-1032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2012.706261

Amianto, F., Caroppo, P., D’Agata, F., Spalatro, A., Lavagnino, L., Caglio, M., Righi, D., Bergui, M., Abbate-Daga, G., Rigardetto, R., Mortara, P., & Fassino, S. (2013). Brain volumetric abnormalities in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 213(3), 210-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.03.010

Amlung M, Marsden E, Holshausen K, et al. Delay Discounting as a Transdiagnostic Process in Psychiatric Disorders: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(11):1176–1186. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2102

Apps, M. A. J., & Ramnani, N. (2014). The anterior cingulate gyrus signals the net value of others’ rewards. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(18), 6190-6200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2701-13.2014

Auerbach, R. P., Stewart, J. G., & Johnson, S. L. (2017). Impulsivity and Suicidality in Adolescent Inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(1), 91-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0146-8

Bari, A., & Robbins, T. W. (2013). Noradrenergic versus dopaminergic modulation of impulsivity, attention and monitoring behaviour in rats performing the stop-signal task: Possible relevance to ADHD. Psychopharmacology, 230(1), 89-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00213-013-3141-6

Barratt, E. S. (1965). Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychological Reports, 16(2), 547-554. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1965.16.2.547

Bechara, A. (2005). Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11), 1458-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn1584

Berg, J. M., Latzman, R. D., Bliwise, N. G., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2015). Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1129-1146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pas0000111

Bohon, C., & Stice, E. (2011). Reward abnormalities among women with full and subthreshold bulimia nervosa: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study.International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(7), 585-595. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.20869

Boswell, J. F., Anderson, L. M., & Anderson, D. A. (2015). Integration of interoceptive exposure in eating disorder treatment: Science and Practice. Clinical Psychology, 22(2), 194–210. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12103

Brockmeyer, T., Skunde, M., Wu, M., Bresslein, E., Rudofsky, G., Herzog, W., & Friederich, H. (2014). Difficulties in emotion regulation across the spectrum of eating disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 565-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.001

Brooks, S. J., Barker, G. J., O’Daly, O. G., Brammer, M., Williams, S. C. R., Benedict, C., Schiöth, H. B., Treasure, J., & Campbell, I. C. (2011). Restraint of appetite and reduced regional brain volumes in anorexia nervosa: A voxel-based morphometric study. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 11. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/restraint-appetite-reduced-regional-brain-volumes/docview/1634755313/se-2

Brooks, S. J., O’Daly, O. G., Uher, R., Friederich, H., Giampietro, V., Brammer, M., Williams, S. C. R., Schiöth, H. B., Treasure, J., & Campbell, I. C. (2011). Differential neural responses to food images in women with bulimia versus anorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE, 6(7), 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022259

Brunyé, T. T., Hayes, J. F., Mahoney, C. R., Gardony, A. L., Taylor, H. A., & Kanarek, R. B. (2013). Get in My Belly: Food Preferences Trigger Approach and Avoidant Postural Asymmetries. PLoS One, 8(8). Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection; ProQuest One Academic. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072432

Buckholdt, K. E., Parra, G. R., & Jobe-shields, L. (2014). Intergenerational Transmission of Emotion Dysregulation Through Parental Invalidation of Emotions: Implications for Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors.Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 324-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9768-4

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., Joormann, J., Kim, Y., & Nam, J. Y. (2011). Serotonin transporter polymorphism interacts with childhood adversity to predict aspects of impulsivity. Psychological Science, 22(5), 589-595. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797611404085

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., & Timpano, K. R. (2017). Toward a Functional View of the P Factor in Psychopathology. Clinical psychological science: a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 5(5), 880–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617710037

Carver, C. S., & Johnson, S. L. (2018). Impulsive reactivity to emotion and vulnerability to psychopathology. American Psychologist, 73(9), 1067–1078. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000387

Chester, D. S., Lynam, D. R., Milich, R., Powell, D. K., Andersen, A. H., & DeWall, C. N. (2016). How do negative emotions impair self-control? A neural model of negative urgency. NeuroImage, 132, 43-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.024

Contreras‐Rodríguez, O., Albein‐Urios, N., Vilar‐López, R., Perales, J. C., Martínez‐Gonzalez, J. M., Fernández‐Serrano, M. J., Lozano‐Rojas, O., Clark, L., & Verdejo‐García, A. (2016). Increased corticolimbic connectivity in cocaine dependence versus pathological gambling is associated with drug severity and emotion‐related impulsivity. Addiction Biology, 21(3), 709-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/adb.12242

Conviser, J. H., Fisher, S. D., & McColley, S. A. (2018). Are children with chronic illnesses requiring dietary therapy at risk for disordered eating or eating disorders? A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(3), 187-213. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22831

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2007). Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 839-850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008

Cyders, M. A., Smith, G. T., Spillane, N. S., Fischer, S., Annus, A. M., & Peterson, C. (2007). Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 107-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 807–828. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013341

Cyders, M. A., Zapolski, T. C. B., Combs, J. L., Settles, R. F., Fillmore, M. T., & Smith, G. T. (2010). Experimental effect of positive urgency on negative outcomes from risk taking and on increased alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 367-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019494

Davis-Becker, K., Peterson, C. M., & Fischer, S. (2014). The relationship of trait negative urgency and negative affect to disordered eating in men and women. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 9–14. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.010

Dawson, D. N., Eisenlohr‐Moul, T. A., Paulson, J. L., Peters, J. R., Rubinow, D. R., & Girdler, S. S. (2018). Emotion‐related impulsivity and rumination predict the perimenstrual severity and trajectory of symptoms in women with a menstrually related mood disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 579-593. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22522

Dekker, M. R., & Johnson, S. L. (2018). Major depressive disorder and emotion-related impulsivity: Are both related to cognitive inhibition? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(4), 398-407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9885-2

Depue, R. A. (1995). Neurobiological factors in personality and depression. European Journal of Personality, 9(5), 413-439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/per.2410090509

Den Ouden Lauren, Suo Chao, Albertella Lucy, Greenwood Lisa-Marie, Lee, R. S., C., Fontenelle, L. F., Parkes Linden, Jeggan, T., Chamberlain, S. R., Richardson, K., Segrave, R., & Yücel Murat. (2022). Transdiagnostic phenotypes of compulsive behavior and associations with psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological affective processing. Translational Psychiatry, 12(1). ProQuest One Academic. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01773-1

Dickman, S. J. (1990). Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity: Personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 95-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.95

Dixon-gordon, K. L., Chapman, A. L., Weiss, N. H., & Rosenthal, M. Z. (2014). A Preliminary Examination of the Role of Emotion Differentiation in the Relationship Between Borderline Personality and Urges for Maladaptive Behaviors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(4), 616–625. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9423-4

Eisenberg, N. (2004). Emotion-Related Regulation: An Emerging Construct. Merrill – Palmer Quarterly, 50(3), 236-259. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/emotion-related-regulation-emerging-construct/docview/230093667/se-2?accountid=48841

Eisenberg, N., Edwards, A., Spinrad, T. L., Sallquist, J., Eggum, N. D., & Reiser, M. (2013). Are effortful and reactive control unique constructs in young children?Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2082-2094. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031745

Fergus, K. B., Copp, H. L., Tabler, J. L., & Nagata, J. M. (2019). Eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors among women: Associations with sexual risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(11), 1310-1315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.23132

Ferriter, C., & Ray, L. A. (2011). Binge eating and binge drinking: An integrative review. Eating Behaviors, 12(2), 99-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.01.001

Fischer, S., & Smith, G. T. (2008). Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(4), 789-800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.008

Fischer, S., Smith, G. T., & Cyders, M. A. (2008). Another look at impulsivity: A meta-analytic review comparing specific dispositions to rash action in their relationship to bulimic symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(8), 1413-1425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.001

Frank, G. K., Shott, M. E., Hagman, J. O., & Mittal, V. A. (2013). Alterations in brain structures related to taste reward circuitry in ill and recovered anorexia nervosa and in bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(10), 1152-1160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101294

Frank, G. K. W., Reynolds, J. R., Shott, M. E., & O’Reilly, R. C. (2011). Altered temporal difference learning in bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry, 70(8), 728-735. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.011

Frederiksen, T. C., Christiansen, M. K., Clausen, L., & Jensen, H. K. (2021). Early repolarization pattern in adult females with eating disorders. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology (Online), 26(5)https://doi.org/10.1111/anec.12865

Hall, N. T., & Hallquist, M. N. (2022). Dissociation of basolateral and central amygdala effective connectivity predicts the stability of emotion-related impulsivity in adolescents and emerging adults with borderline personality symptoms: A resting-state fmri study. Psychological Medicine. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722000101

Harrison, A., Sullivan, S., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2009). Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(4), 348-356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cpp.628

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 86-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86

Heiland, A. M., & Veilleux, J. C. (2021). Severity of personality dysfunction predicts affect and self-efficacy in daily life. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 12(6), 560-569. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/per0000470

Hemmingsson E. Early Childhood Obesity Risk Factors: Socioeconomic Adversity, Family Dysfunction, Offspring Distress, and Junk Food Self-Medication. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7(2):204-209. doi:10.1007/s13679-018-0310-2

Herbert, B. M., & Pollatos, O. (2012). The body in the mind: On the relationship between interoception and embodiment. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 692-704. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01189.x

Ireland, J. L., & Archer, J. (2008). Impulsivity among adult prisoners: A confirmatory factor analysis study of the Barratt impulsivity scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(4), 286-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.012

Izydorczyk, B. (2013). Aggression and self-aggression syndrome in females suffering from bulimia nervosa. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 44(4), 384-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/ppb-2013-0042

Jaggers, J. A., & Gruber, J. (2020). Mixed mood states and emotion-related urgency in bipolar spectrum disorders: A call for greater investigation. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 8, 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0171-y

Johnson, S. L., Carver, C. S., Mulé, S., & Joormann, J. (2013). Impulsivity and risk for mania: Towards greater specificity. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(4), 401-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2012.02078.x

Johnson, S. L., Tharp, J. A., Peckham, A. D., Sanchez, A. H., & Carver, C. S. (2016). Positive urgency is related to difficulty inhibiting prepotent responses. Emotion, 16(5), 750–759. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000182

Johnson, S. L., Sandel, D. B., Zisser, M., Pearlstein, J. G., Swerdlow, B. A., Sanchez, A. H., Fernandez, E., & Carver, C. S. (2020). A brief online intervention to address aggression in the context of emotion-related impulsivity for those treated for bipolar disorder: Feasibility, acceptability and pilot outcome data. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 30(1), 65–74. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2020.03.005

Johnson, S. L., Zisser, M. R., Sandel, D. B., Swerdlow, B. A., Carver, C. S., Sanchez, A. H., & Fernandez, E. (2020). Development of a brief online intervention to address aggression in the context of emotion-related impulsivity: Evidence from a wait-list controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 134, 11. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103708

Jones, A. C., Lim, S., Hood, C. O., Brake, C. A., & Badour, C. L. (2021). Affective lability moderates the associations between negative and positive urgency and posttraumatic stress. Traumatology: An International Journal, 27(3), 265–273. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000270

Kaye W. (2008). Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiology & behavior, 94(1), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037

Kenneth J. D. Allen, Sheri L. Johnson, Taylor A. Burke, M. McLean Sammon, Christina Wu, Max A. Kramer, Jinhan Wu, Heather T. Schatten, Michael F. Armey, Jill M. Hooley. Validation of an emotional stop-signal task to probe individual differences in emotional response inhibition: Relationships with positive and negative urgency. Brain and Neuroscience Advances, 2021; 5: 239821282110582 DOI: 10.1177/23982128211058269

Kenny, T. E., & Carter, J. C. (2018). I weigh therefore I am: Implications of using different criteria to define overvaluation of weight and shape in binge‐eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(11), 1244-1251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.22956

Kenny, T. E., Megan, V. W., Singleton, C., & Carter, J. C. (2018). An examination of the relationship between binge eating disorder and insomnia symptoms.European Eating Disorders Review, 26(3), 186-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/erv.2587

Kenny, T. E., Singleton, C., & Carter, J. C. (2019). An examination of emotion-related facets of impulsivity in binge eating disorder. Eating Behaviors, 32, 74–77. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.12.006

Leon, G. R., Carroll, K., Chernyk, B., & Finn, S. (1985). Binge eating and associated habit patterns within college student and identified bulimic populations.International Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(1), 43-57. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/binge-eating-associated-habit-patterns-within/docview/49180973/se-2?accountid=48841

Magel, C. A., & von Ranson, K. M. (2021). negative urgency combined with negative emotionality is linked to eating disorder psychopathology in community women with and without binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(5), 821–830. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23491

Manasse, S. M., Juarascio, A. S., Forman, E. M., Zhang, F., Espel, H. M., Schumacher, L. M., & Kerrigan, S. G. (2016). Does impulsivity predict outcome in treatment for binge eating disorder? A multimodal investigation. Appetite, 105, 172-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.026

Marcus, M. D. (2018). Obesity and eating disorders: Articles from the International Journal of Eating Disorders 2017–2018. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(11), 1296-1299. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22974

Martins-Klein, B., Alves, L. A., & Chiew, K. S. (2020). Proactive versus reactive emotion regulation: A dual-mechanisms perspective. Emotion, 20(1), 87-92. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000664

Masuda, A., Price, M., & Latzman, R. D. (2012). Mindfulness moderates the relationship between disordered eating cognitions and disordered eating behaviors in a non-clinical college sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(1), 107-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-011-9252-7

McDonald, C. E., Rossell, S. L., & Phillipou, A. (2019). The comorbidity of eating disorders in bipolar disorder and associated clinical correlates characterised by emotion dysregulation and impulsivity: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 228-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.070

Michael Amlung et al. Delay Discounting as a Transdiagnostic Process in Psychiatric Disorders: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, August 28, 2019 DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2102

Miglin, R., Bounoua, N., Goodling, S., Sheehan, A., Spielberg, J. M., & Sadeh, N. (2019). Cortical Thickness Links Impulsive Personality Traits and Risky Behavior. Brain Sciences, 9(12), 373. ProQuest One Academic. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9120373

Mittal, V. A., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2017). Research domain criteria (RDoC) grows up: Strengthening neurodevelopmental investigation within the RDoC framework. Journal of Affective Disorders, 216, 30-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.011

Moore, M., Masuda, A., Hill, M. L., & Goodnight, B. L. (2014). Body image flexibility moderates the association between disordered eating cognition and disordered eating behavior in a non-clinical sample of women: A cross-sectional investigation. Eating Behaviors, 15(4), 664-669. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.08.021

Muhtadie, L., Johnson, S. L., Carver, C. S., Gotlib, I. H., & Ketter, T. A. (2014). A profile approach to impulsivity in bipolar disorder: The key role of strong emotions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 129(2), 100-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acps.12136

Muhlert, N., & Lawrence, A. (2015). Brain structure correlates of emotion-based rash impulsivity. NeuroImage, 115, 138–146. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.061

Nordgren, L., Ghaderi, A., Ljótsson, B., & Hesser, H. (2021). Identifying subgroups of patients with eating disorders based on emotion dysregulation profiles: A factor mixture modeling approach to classification. Psychological Assessment. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001103

Pak, K. N., Wonderlich, J., Daniel le Grange, Engel, S. G., Crow, S., Peterson, C., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., & Fischer, S. (2018). The moderating effect of impulsivity on negative affect and body checking. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 86, 137–142. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.08.007

Pearlstein, J. G., Johnson, S. L., Modavi, K., Peckham, A. D., & Carver, C. S. (2019). Neurocognitive mechanisms of emotion‐related impulsivity: The role of arousal. Psychophysiology, 56(2), 1–9. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13293

Pearson, M. R., Kite, B. A., & Henson, J. M. (2012). Unique direct and indirect effects of impulsivity-like traits on alcohol-related outcomes via protective behavioral strategies. Journal of Drug Education, 42(4), 425-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/DE.42.4.d

Pearson, C. M., Combs, J. L., & Smith, G. T. (2010). A risk model for disordered eating in late elementary school boys. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 696–704. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020358

Pearson, C. M., Wonderlich, S. A., & Smith, G. T. (2015). A risk and maintenance model for bulimia nervosa: From impulsive action to compulsive behavior. Psychological Review, 122(3), 516–535. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039268

Peckham, A. D., Forgeard, M., Hsu, K. J., Beard, C., & Bjorgvinsson Thröstur Björgvinsson. (2019). Turning the UPPS down: Urgency predicts treatment outcome in a partial hospitalization program. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 88, 70–76. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.11.005

Peckham, A. D., & Johnson, S. L. (2018). Cognitive control training for emotion-related impulsivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 105, 17–26. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.03.009

Peters, J. R., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., Walsh, E. C., & Derefinko, K. J. (2018). Exploring the pathophysiology of emotion-based impulsivity: The roles of the sympathetic nervous system and hostile reactivity. Psychiatry Research, 267, 368–375. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.013

Petrie, T. A., Greenleaf, C., Reel, J., & Carter, J. (2008). Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors among male collegiate athletes. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 9(4), 267-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013178

Pisetsky, E. M., Haynos, A. F., Lavender, J. M., Crow, S. J., & Peterson, C. B. (2017). Associations between emotion regulation difficulties, eating disorder symptoms, non-suicidal self-injury, and suicide attempts in a heterogeneous eating disorder sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 73, 143-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.012

Pisetsky, E. M., Peterson, C. B., Mitchell, J. E., Wonderlich, S. A., Crosby, R. D., Le Grange, D., Hill, L., Powers, P., & Crow, S. J. (2017). A comparison of the frequency of familial suicide attempts across eating disorder diagnoses.International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(6), 707-710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.22694

Racine, S. E., Burt, S. A., Keel, P. K., Sisk, C. L., Neale, M. C., Boker, S., & Klump, K. L. (2015). Examining associations between negative urgency and key components of objective binge episodes. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(5), 527-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.22412

Racine, S. E., VanHuysse, J. L., Keel, P. K., Burt, S. A., Neale, M. C., Boker, S., & Klump, K. L. (2017). Eating disorder-specific risk factors moderate the relationship between negative urgency and binge eating: A behavioral genetic investigation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(5), 481–494. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000204

Reichenberger, J., Schnepper, R., Ann-Kathrin Arend, & Blechert, J. (2020). Emotional eating in healthy individuals and patients with an eating disorder: Evidence from psychometric, experimental and naturalistic studies. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 79(3), 290–299. Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection; ProQuest One Academic. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665120007004

Riley, E. N., Combs, J. L., Jordan, C. E., & Smith, G. T. (2015). negative urgency and lack of perseverance: Identification of differential pathways of onset and maintenance risk in the longitudinal prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury.Behavior Therapy, 46(4), 439-448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2015.03.002

Robinson, M. D., & Klein, R. J. (2021). The momentary and the macro in action control: A motor control analysis of impulse control difficulties. Emotion, https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000976

VanderBroek-Stice, L., Stojek, M. K., Beach, S. R. H., vanDellen, M. R., & MacKillop, J. (2017). Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in relation to obesity and food addiction. Appetite, 112, 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.009

Selby, E. A., & Coniglio, K. A. (2020). Positive emotion and motivational dynamics in anorexia nervosa: A positive emotion amplification model (PE-AMP).Psychological Review, 127(5), 853-890. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rev0000198

Sharma, L., Markon, K. E., & Clark, L. A. (2014). Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: A meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures.Psychological Bulletin, 140(2), 374-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034418

Shumlich, E. J. (2017). Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Eating Disorders: Mood Intolerance as a Common Treatment Target. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy (Online), 51(3), 217–229. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database.

Smith, G. T., Fischer, S., Cyders, M. A., Annus, A. M., Spillane, N. S., & McCarthy, D. M. (2007). On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment, 14(2), 155-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191106295527

Smith, G. T., Guller, L., & Zapolski, T. C. B. (2013). A comparison of two models of urgency: Urgency predicts both rash action and depression in youth. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(3), 266-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2167702612470647

Smyth, J. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Heron, K. E., Sliwinski, M. J., Crosby, R. D., Mitchell, J. E., & Engel, S. G. (2007). Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 629-638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629

Snyder, H. R., Gulley, L. D., Bijttebier, P., Hartman, C. A., Oldehinkel, A. J., Mezulis, A., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2015). Adolescent emotionality and effortful control: Core latent constructs and links to psychopathology and functioning.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1132. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/adolescent-emotionality-effortful-control-core/docview/1749621687/se-2

Sperry, S. H., Sharpe, B. M., & Wright, A. G. C. (2021). Momentary dynamics of emotion-based impulsivity: Exploring associations with dispositional measures of externalizing and internalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(8), 815–828. APA PsycArticles®. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000720

Spoont, M. R. (1992). Modulatory role of serotonin in neural information processing: Implications for human psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 330-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.330

Sokić, K., Horvat, Đ., & Martinčić, S. G. (2020). How Impulsivity influences the Post-purchase Consumer Regret? Business Systems Research, 11(3), 14-29. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsrj-2020-0024

Tan, O., Musullulu, H., Raymond, J. S., Wilson, B., Langguth, M., & Bowen, M. T. (2019). Oxytocin and vasopressin inhibit hyper-aggressive behaviour in socially isolated mice. Neuropharmacology, 156http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.016

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Schvey, N. A., & Grilo, C. M. (2020). A developmental framework of binge-eating disorder based on pediatric loss of control eating. The American Psychologist, 75(2), 189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000592

Terres-Barcala, L., Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Aparicio-Ugarriza, R., Ruiz-Robledillo, N., Zaragoza-Martí, A., & Ferrer-Cascales, R. (2022). Effects of Impulsivity on Competitive Anxiety in Female Athletes: The Mediating Role of Mindfulness Trait. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3223. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063223

Todd, J., Barron, D., Aspell, J. E., Lin Toh, E. K., Zahari, H. S., Mohd. Khatib, N. A., & Swami, V. (2022). Examining relationships between interoceptive sensibility and body image in a non-western context: A study with Malaysian adults. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 11(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1027/2157-3891/a000022

Tomoya, H., Deserno, M., & McElroy, E. (2020). The Network Structure of Irritability and Aggression in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(4), 1210-1220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04354-w

Um, M., Whitt, Z. T., Revilla, R., Taylor Hunton, & Cyders, M. A. (2019). Shared Neural Correlates Underlying Addictive Disorders and Negative Urgency. Brain Sciences, 9(2). ProQuest One Academic. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020036

Victor, S. E., Johnson, S. L., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Quality of life and impulsivity in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 13(3), 303-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00919.x

Vitale, E. M., & Smith, A. S. (2022). Neurobiology of Loneliness, Isolation, and Loss: Integrating Human and Animal Perspectives. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.846315

Walenda, A., Kostecka, B., Santangelo, P. S., & Kucharska, K. (2021). Examining emotion regulation in binge-eating disorder. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation, 8(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-021-00166-6

Weiss, N. H., Tull, M. T., Davis, L. T., Searcy, J., Williams, I., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). A Preliminary Experimental Investigation of Emotion Dysregulation and Impulsivity in Risky Behaviours. Behaviour Change, 32(2), 127–142. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database.

Wegner, K. E., Smyth, J. M., Crosby, R. D., Wittrock, D., Wonderlich, S. A., & Mitchell, J. E. (2002). An evaluation of the relationship between mood and binge eating in the natural environment using ecological momentary assessment.International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32(3), 352-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.10086

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669-689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7

Whiteside, S. P., Lynam, D. R., Miller, J. D., & Reynolds, S. K. (2005). Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity.European Journal of Personality, 19(7), 559-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/per.556

Wilbertz, T., Deserno, L., Horstmann, A., Neumann, J., Villringer, A., Heinze, H., Boehler, C. N., & Schlagenhauf, F. (2014). Response inhibition and its relation to multidimensional impulsivity. NeuroImage, 103, 241-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.021

Williams, L. M., Mathersul, D., Palmer, D. M., Gur, R. C., Gur, R. E., & Gordon, E. (2008). Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: I. Age effects in males and females across 10 decades. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 31(3), 257-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803390802255635

Wolz, I., Granero, R., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2017). A comprehensive model of food addiction in patients with binge-eating symptomatology: The essential role of negative urgency. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 118–124. ProQuest One Academic; Psychology Database. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.01.012

Young, H. A., Williams, C., Pink, A. E., Freegard, G., Owens, A., & Benton, D. (2017). Getting to the heart of the matter: Does aberrant interoceptive processing contribute towards emotional eating? PLoS One, 12(10)https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186312

Zalar, B., Weber, U., & Sernec, K. (2011). Aggression and impulsivity with impulsive behaviours in patients with purgative anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychiatria Danubina, 23(1), 27-33. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/aggression-impulsivity-with-impulsive-behaviours/docview/885701818/se-2?accountid=48841

Zhou, H., Martinez, E., Lin, H. H., Yang, R., Jahrane, A. D., Liu, K., Huang, D., & Wang, J. (2018). Inhibition of the Prefrontal Projection to the Nucleus Accumbens Enhances Pain Sensitivity and Affect. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.00240

Zorrilla, E. P., & Koob, G. F. (2019). Impulsivity derived from the dark side: Neurocircuits that contribute to negative urgency. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 15. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00136

Related Posts

3D Bioprinting: An Innovative Approach to Promote Cartilage Regeneration

Source: Laboratoires Servier, (CC BY-SA 3.0) Many of us cannot...

Read MoreBispecific Antibody Recruits Vγ9+ γδ T cells for Leukemia Treatment

Figure 1: The image is taken from an elderly woman...

Read MoreHealth Literacy in the United States

This publication is in proud partnership with Project UNITY’s Catalyst...

Read MoreWhy Young Investigators Should Consider Prehospital Care Research

Figure 1: The author (14 hours and 10 patients into...

Read MoreAnother Reason To Get More Sleep

Figure 1: Some of the major detrimental effects of sleep...

Read MoreTrust: The Essence of Good Policy Implementation

Figure 1 President Tsai Ing-wen inspects the Central Epidemic Command...

Read MoreMingcong Tang